Medicine and Health

Ingested nitrate and nitrite and end-stage renal disease in licensed pesticide applicators and spouses in the Agricultural Health Study

D. Chen, C. G. Parks, et al.

This intriguing study reveals a potential link between processed meat consumption and the risk of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in pesticide applicators and their spouses. Conducted by a team of experts including Dazhe Chen and Christine G. Parks, the research highlights the importance of dietary choices in influencing health outcomes.

~3 min • Beginner • English

Introduction

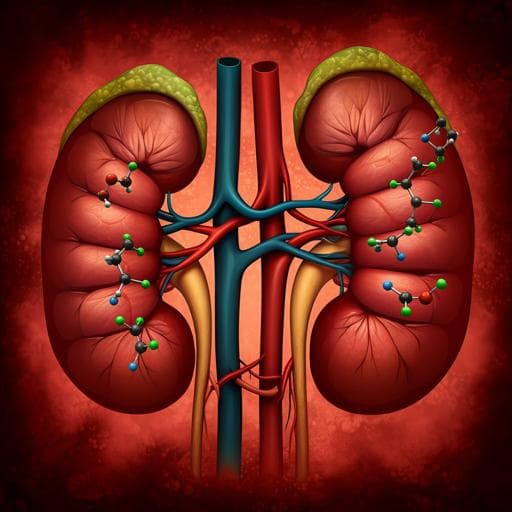

End-stage renal disease (ESRD), the terminal stage of chronic kidney disease (CKD), is a major public health problem with high morbidity, mortality, and cost. Traditional risk factors (diabetes, hypertension) do not fully explain ESRD burden, and CKD of unknown etiology has emerged in agricultural regions, implicating environmental/occupational exposures. Inorganic nitrate, a common groundwater contaminant from fertilizers and wastes, and dietary nitrate/nitrite may lead to endogenous nitrosation and formation of carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds (NOCs) with potential renal toxicity. Prior work linked nitrate/nitrite to kidney cancer and suggested nitrate in drinking water might be related to unexplained ESRD clusters. This study evaluates whether drinking water nitrate and dietary nitrate/nitrite (overall and by food source) are associated with incident ESRD in the Agricultural Health Study cohort and explores effect modification by vitamin C (an inhibitor of nitrosation) and heme iron (an enhancer).

Literature Review

Background literature indicates CKD/ESRD has multifactorial causes with environmental contributors suspected in agricultural areas. Ecologic mapping in California linked elevated groundwater nitrate to ESRD hotspots, and high nitrate has been reported in regions with CKDu (Sri Lanka, Western Australia). Studies on nitrate/nitrite and renal outcomes are limited: experimental studies show no acute kidney function changes with short-term nitrate supplementation; observational data on dietary nitrate and CKD are mixed. For cancer, several studies associate nitrite from processed/animal sources with kidney cancer risk, whereas plant-derived nitrate/nitrite and total nitrate often show null associations. Mechanistically, nitrate can be reduced to nitrite, which can nitrosate amines/amides to form NOCs; heme iron promotes and vitamin C inhibits nitrosation. Prior epidemiologic studies suggest stronger adverse associations where nitrosation enhancers are high and inhibitors are low.

Methodology

Design and population: Prospective cohort analysis within the Agricultural Health Study (AHS) of licensed pesticide applicators and their spouses in Iowa and North Carolina. Enrollment: 1993–1997 (baseline questionnaire). Dietary data: Phase 2 (1999–2003) Diet History Questionnaire (DHQ). Exclusions included prevalent ESRD prior to relevant baseline, missing exposure/covariate data, and non-eligible water sources. Final analytical samples: water nitrate analysis N=59,632 (469 ESRD cases); dietary nitrate/nitrite analysis N=30,177 (206 ESRD cases). Exposure assessment: Drinking water source (private well or PWS) at enrollment ascertained; PWS nitrate-nitrogen (NO3-N, mg/L) averaged across years of residence in 1990–2000 from state monitoring data (IA 1987–2018; NC 1977–2018). Private well NO3-N predicted around enrollment using state-specific random forest models trained on extensive groundwater nitrate datasets (IA: 34,084 measurements, 1980–2011; NC: 22,059 measurements, 1990–2011) with predictors including well depth (state median imputed if missing), land use, nitrogen inputs, population density, soils, geology, and meteorology. Dietary intake: Nitrate (mg NO3/day) and nitrite (mg NO2/day) estimated from the 144-item NCI DHQ using a literature-derived nitrate/nitrite database; totals and source-specific intakes (plant, animal, processed meat) computed. Vitamin C intake (foods and supplements) and heme iron intake estimated from validated nutrient databases. Outcome ascertainment: Incident ESRD through June 30, 2018 via linkage to the U.S. Renal Data System (USRDS); first ESRD service date used for event timing. Vital status via state mortality files and National Death Index. Follow-up: For water analysis, from age at enrollment to ESRD, death, withdrawal, or 6/30/2018. For dietary analysis, from age at P2 completion to the same endpoints. Covariates: Age (time scale), sex, state, education, smoking status; plus total energy intake for dietary models. Additional variables described (race/ethnicity, BMI, diabetes, pesticide use, residence duration) used in sensitivity analyses and descriptive summaries. Statistical analysis: Cox proportional hazards models with age as time scale; exposures categorized into tertiles (T1 referent). Fully adjusted models: water—age, sex, state, education, smoking; diet—age, sex, state, education, smoking, total calories. Minimally adjusted models (age only) also fit. Effect measure modification assessed by strata of vitamin C median (146.3 mg/day), heme iron median (403.8 mg/day), sex (applicators vs spouses), state (IA vs NC), and (for water) drinking water source (PWS vs private well). Interaction tested via joint Wald tests with product terms. Sensitivity analyses: Exclusion of pre-enrollment diabetes; additional adjustment for BMI, lifetime days of any pesticide use, year of enrollment; comparisons of T3 above 90th percentile vs T1; quartiles of water nitrate; restriction to residence duration ≥10 years; nutrient density adjustment (mg/1000 kcal) for diet. Analyses conducted in SAS 9.4 with alpha=0.05.

Key Findings

- ESRD cases: 469/59,632 (water analysis); 206/30,177 (dietary analysis). Median follow-up ≈ 268 months. Most water nitrate exposures were below the EPA MCL (10 mg/L). Most dietary nitrate/nitrite intake came from plants. - Drinking water nitrate (average NO3-N): No association with ESRD in minimally or fully adjusted models. Fully adjusted HRs: T2 vs T1: 1.02 (95% CI: 0.82, 1.27); T3 vs T1: 0.90 (0.72, 1.14). No heterogeneity by drinking water source, state, or sex; no modification by vitamin C or heme iron. Sensitivity analyses (excluding diabetes; adjusting for BMI, pesticide use, enrollment year; 90th percentile comparisons; quartiles; residence ≥10 years) were similarly null. - Total dietary nitrate: No association (Fully adjusted HR T2 vs T1: 0.73 [0.50, 1.06]; T3 vs T1: 1.04 [0.71, 1.52]). - Total dietary nitrite: Modestly elevated but imprecise association (Fully adjusted HR T3 vs T1: 1.36 [0.83, 2.21]). - By food source: • Plant nitrate/nitrite: No association (e.g., nitrate T3 vs T1: 0.97 [0.67, 1.41]). • Animal-source nitrite: Elevated but not statistically significant after full adjustment (T3 vs T1: 1.50 [0.97, 2.33]). • Processed meat nitrate: Increased ESRD risk (T3 vs T1: 2.05 [1.37, 3.05]). • Processed meat nitrite: Increased ESRD risk with dose-response (T2 vs T1: 1.60 [1.09, 2.34]; T3 vs T1: 2.22 [1.47, 3.34]). - Effect modification by dietary factors: • Vitamin C: Among participants below median vitamin C intake, total dietary nitrite T3 vs T1 HR: 2.26 (1.05, 4.86); no association above median. Interaction p for nitrite=0.69 (not statistically significant). • Heme iron: Among participants at/above median heme iron, total dietary nitrite T3 vs T1 HR: 1.73 (0.89, 3.39) and dietary nitrate T3 vs T1 HR: 1.22 (0.72, 2.06); no positive associations below median. Interaction p for nitrite=0.70; nitrate=0.59. - Sex/state subgroups: Modestly elevated, non-significant association for dietary nitrite T3 among male applicators; stronger associations among North Carolina participants in stratified analyses; water nitrate null across subgroups.

Discussion

The study addressed whether nitrate in drinking water and nitrate/nitrite from diet are associated with incident ESRD. Findings indicate no association for water nitrate, while dietary nitrite and nitrate from processed meats were associated with higher ESRD risk, consistent with the hypothesis that endogenous nitrosation contributes to renal damage. Processed and animal meats provide amines/amides and heme iron, promoting formation of N-nitroso compounds; processed meats may also contain added nitrite and are often cooked at high temperatures, generating additional toxicants. In contrast, plant sources include vitamin C and antioxidants that inhibit nitrosation, potentially explaining null associations for plant-derived nitrate/nitrite. Subgroup findings showing higher ESRD risk with total dietary nitrite among those with lower vitamin C intake and higher heme iron intake align with biological plausibility for nitrosation-mediated effects, although formal interaction tests were not statistically significant. The null results for water nitrate, including across extensive sensitivity analyses, suggest that at the generally low to moderate exposure levels observed in this cohort, drinking water nitrate may not substantially influence ESRD risk. Results complement and extend prior research on nitrate/nitrite and kidney cancer and provide individual-level, confounder-adjusted evidence regarding ESRD.

Conclusion

In a large agricultural cohort, drinking water nitrate was not associated with ESRD. Higher intake of dietary nitrite and nitrate from processed meats was associated with increased ESRD risk, with stronger associations observed among individuals with lower vitamin C or higher heme iron intake, consistent with enhanced endogenous nitrosation. These findings provide preliminary evidence that dietary nitrite (and possibly nitrate), particularly from processed meats, may contribute to ESRD in susceptible subgroups. Further studies in more diverse, non-occupational populations and investigations of earlier CKD endpoints and biomarkers are warranted to confirm associations and clarify timing and mechanisms.

Limitations

- Selection and generalizability: Analyses restricted to participants with complete exposure and covariate data; dietary analyses limited to DHQ respondents. Cohort predominantly White and non-Hispanic and agricultural, limiting generalizability and precluding race/ethnicity-specific analyses. - Exposure misclassification: Private well nitrate predictions required imputation of well depth for a subset; residential address at enrollment used to assign exposures with limited temporal coverage around enrollment; lack of post-enrollment private well data. Potential non-differential misclassification likely biases toward the null. - Outcome scope: Incident ESRD used; CKD often precedes ESRD by years, limiting inference about disease initiation versus progression. - Residual confounding: Potential unmeasured/unknown confounders (e.g., other water contaminants, heavy metals, heat stress/dehydration) and measurement error in covariates. Self-reported diabetes may be imperfect. - Limited power in subgroups: Some subgroup and interaction analyses had wide confidence intervals and non-significant tests for interaction.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.