Veterinary Science

The expression signatures in liver and adipose tissue from obese Göttingen Minipigs reveal a predisposition for healthy fat accumulation

S. Cirera, E. Taşöz, et al.

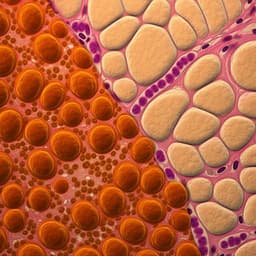

The study investigates why Göttingen Minipigs fed a high fat, fructose and cholesterol (FFC) diet develop severe obesity and dyslipidemia yet lack hallmark hepatic features of human NAFLD/NASH (abundant macrovesicular steatosis and hepatocellular ballooning). It contextualizes obesity’s links to metabolic syndrome/T2DM and NAFLD/NASH, emphasizing that metabolic health, including the mechanism of adipose tissue expansion, is more determinant than obesity per se. The adipose tissue expandability hypothesis proposes that individuals with greater capacity to store lipid in adipose depots can remain metabolically healthy (metabolically healthy obese, MHO). Prior pig models show limited hepatic macrovesicular steatosis despite diet-induced metabolic disturbances. The purpose here is to characterize transcriptional changes in liver, SAT and VAT to explain limited hepatic steatosis and define molecular mechanisms underlying histopathology in FFC-fed Göttingen Minipigs, including those with superimposed diabetes.

The paper reviews: (1) the adipose tissue expandability hypothesis, where capacity for adipose storage predicts metabolic health more than fat mass itself; (2) prior minipig models (Bama, Ossabaw, Göttingen) subjected to Western/atherogenic diets often display fibrosis, inflammation and insulin resistance but typically only limited, primarily microvesicular hepatic steatosis, unlike human macrovesicular steatosis; (3) previous evidence for an MHO-like phenotype in Göttingen Minipigs and genetic predisposition toward healthier lipid handling; and (4) differences between pigs and humans/rodents in hepatic lipid metabolism (e.g., pig liver is not the primary site of de novo lipogenesis). This background underscores the need to delineate molecular pathways in pigs that decouple obesity from severe hepatic steatosis.

Design and animals: Castrated male Göttingen Minipigs (n=84 initially; 29 included for this study), age 6–7 months, weight-stratified into six groups overall; three groups analyzed here for 13 months: SD (standard chow; n=7), FFC (high fat/fructose/cholesterol; n=14; 2% cholesterol diet for first 5 months then 1% for 8 months), and FFCDIA (streptozotocin-induced diabetes plus 1% cholesterol FFC; n=8). In FFCDIA, type 1-like diabetes was induced with streptozotocin; pigs received daily long-acting insulin to maintain fasting glucose ∼15 mM. Sampling: After overnight fasting, animals were euthanized; samples from liver (left medial lobe), SAT, and VAT were snap frozen for expression studies. Histology on SAT and VAT was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded 3 µm HE-stained sections. RNA isolation: 50 mg liver or 20–180 mg adipose tissue processed with Tri Reagent or an adipose-optimized method; DNase treatment applied. RNA quality assessed (liver RQI 8.10–9.70; SAT mean 8.4; VAT mean 8.2). One SAT and three VAT samples excluded due to low RQI. cDNA synthesis: Reverse transcription with ImProm-II using 500 ng RNA (liver) or 100 ng (adipose); -RT controls included; cDNA dilutions: liver 1:16, adipose 1:8. Gene panel and primers: >90 metabolically relevant genes plus four reference genes per tissue; primers designed via NCBI tools, targeting ~100 nt products, preferably exon-spanning; details in Table S1. qPCR platforms: High-throughput Biomark HD (Fluidigm) using 96.96 IFC chips; preamplification (15 cycles liver/SAT, 14 cycles VAT); Exo I cleanup; SsoFast EvaGreen chemistry; tissue-specific standard curves. Some genes (TGFB1, LDAH, BCL2 in liver; PPARG, CD36 in VAT) re-run on MxPro/Mx3005P (Stratagene) with QuantiFast SYBR Green. For cross-tissue comparison, CD36, FABP4, LPL, PPARG (including PPARG1 and PPARG2 isoform-specific assays) were measured on Mx3005P. Data processing and statistics: PCR efficiencies 80–110% accepted. Normalization to two most stable reference genes (TBP and ACTB in liver/SAT; TBP and YWHAZ in VAT). Technical replicates averaged. Relative expression scaled to the lowest-expressing sample per assay, log2-transformed. Multiple testing correction via Dunn–Bonferroni; significance threshold P<0.0006 for high-confidence hits; additional differentially expressed genes reported at P<0.05. Group comparisons by t-test; metabolic/physical measures analyzed by ANOVA with post hoc t-tests; transformations as needed; Kruskal–Wallis/Wilcoxon for nonparametric cases. Pearson correlations between liver expression of CD36, FABP4, LPL, PPARG and physiological traits performed in R.

Phenotype and metabolism (Table 1): • Body weight (median, IQR): SD 39 kg (38;41), FFC 78 kg (69;81), FFCDIA 60 kg (54;64); P<0.0001. • Liver weight (g): SD 485 (458;564), FFC 1732 (1067;2219), FFCDIA 2077 (1478;2439); P<0.0001. • Total body fat %: SD 28 (24;31), FFC 64 (61;68), FFCDIA 55 (53;56); P<0.0001. • VAT (g): SD 510 (462–543), FFC 2326 (1645–2946), FFCDIA 1335 (1032–1922); P<0.0001 (non-parametric). • Plasma total cholesterol (mmol/L): SD 1.70 (1.64;2.18), FFC 11.94 (11.00;13.18), FFCDIA 18.91 (16.91;27.00); P<0.0001. • Plasma triglycerides (mmol/L): SD 0.34 (0.29;0.35), FFC 0.63 (0.54;0.88), FFCDIA 1.45 (0.57;1.72); P=0.0002. • Plasma glucose (mmol/L): SD 3.48 (3.32;3.67), FFC 3.72 (3.60;3.83), FFCDIA 15.1 (14.67;15.45); P<0.0001. • Liver triglycerides (mg/g): no significant group differences. Liver gene expression (Table 2): • Strong upregulation in FFC vs SD: LPL (FC=172.23; P=1e-08), PPARG (FC=19.08; P≈1.6e-08), CD36 (FC=3.36; P=8.79e-05), CD68 (FC=5.17; P=1e-08). • Strong downregulation in FFC vs SD: KLB (FC=−22.24), HMGCR (FC=−13.36), FDFT1 (FC=−6.31), LDLR (FC=−5.92), SOD1 (FC=−1.76), MTTP (FC=−1.73); many at P<0.0006. • FFCDIA vs SD showed even larger changes for several genes: LPL (FC=308.25; P=1e-08), PPARG (FC=35.56; P≈1.7e-07), FDFT1 (FC=−16.30), KLB (FC=−36.89), CD36 (FC=6.30), FABP4 (FC=11.81), among others. • Additional FFCDIA-specific significant genes after correction included AGT, TLR4, GHR, GCKR, MMP9. • Insulin signaling transcription largely unchanged (IDE, INSIG1/2, IGF1/2, IGFBP2, IRS1 stable); slight downregulation of IRS2 in FFC (FC=−1.73) and FFCDIA (FC=−1.94); INSR slightly down in FFC (FC=−1.32). Adipose tissue expression (Table 3): • SAT: FFC vs SD significant FC>2 or <−1.5 for PN-1 (2.05), EBF2 (−1.69), ABCG1 (2.64), IL6 (2.87). FFCDIA vs SD: ABCG1 (3.89), IL6 (2.67), ABCA1 (2.63), PN-1 (2.77); effects generally modest compared to liver. • VAT: Only one robust hit per comparison—LDLR down in FFC vs SD (−2.17) and RPS29 down in FFCDIA vs SD (−2.28); ABCA1 and ABCG1 upregulated at P<0.05. Cross-tissue expression of PPARG axis: • PPARG and targets (FABP4, LPL, CD36) were markedly upregulated in liver of FFC/FFCDIA, but largely unchanged in SAT/VAT. Both PPARG1 and PPARG2 isoforms detected across tissues; in FFC/FFCDIA livers PPARG expression reached levels comparable to adipose tissues. Correlations (Table 4): • TBF% correlated with VAT mass (r=0.81, P<0.00001). • Liver expression vs adiposity: PPARG (r=0.76, P<0.00001), LPL (r=0.81, P<0.00001), CD36 (r=0.67, P<0.0001) correlated with TBF%; LPL moderately with VAT (r=0.60, P<0.001). • Strong intercorrelation among liver PPARG, LPL, CD36 (r>0.9, P<0.00001); moderate with FABP4 (r>0.6, P<0.001). • No correlation with hepatic triglyceride content. Histology and inflammation: • SAT/VAT showed no increased macrophage infiltration and no crown-like structures in FFC vs SD. • Of pro-inflammatory transcripts (IL18, IL1B, IL6, TLR4, TNF), only IL6 was upregulated in SAT (FC≈2.7–2.9); none upregulated in VAT. Interpretation of lipid/cholesterol pathways: • Despite strong hepatic upregulation of PPARG, CD36, LPL, and FABP4, pigs did not develop abundant hepatic steatosis. • Cholesterol biosynthesis genes HMGCR and FDFT1 were strongly downregulated, consistent with dietary cholesterol suppression; KLB downregulation suggests altered bile acid pathway regulation to handle dietary cholesterol load.

The findings explain the absence of abundant hepatic steatosis in severely obese FFC-fed Göttingen Minipigs by demonstrating: (1) marked hepatic induction of PPARG and its lipid-handling targets (CD36, LPL, FABP4) without concomitant hepatic triglyceride accumulation; (2) preserved adipose tissue metabolic function with minimal inflammatory activation, enabling substantial SAT/VAT expansion; and (3) stable insulin signaling transcript levels, indicating that insulin pathway impairment is not a major driver in this model. Strong correlations between liver PPARG/LPL/CD36 expression and total body fat, alongside unchanged adipose PPARG axis expression, support a model of effective lipid repartitioning from liver to expanding adipose depots. Species-specific metabolism (pig liver is not a primary de novo lipogenesis site) may further protect against steatosis. Downregulation of cholesterol biosynthesis genes likely reflects adaptive responses to high dietary cholesterol, facilitating cholesterol handling via bile acid pathways. Compared to human obesity—often characterized by adipose inflammation and reduced lipogenic/adipogenic gene expression—Göttingen Minipigs resemble a metabolically healthy obese phenotype with greater adipose expandability. This suggests that adipose tissue plasticity can decouple obesity from hepatic metabolic complications.

Severely obese Göttingen Minipigs on an FFC diet exhibit robust adipose tissue expandability and are protected against many metabolic and hepatic abnormalities typically associated with obesity. Despite strong hepatic upregulation of PPARG, CD36, LPL, and FABP4, abundant hepatic steatosis does not develop. Coordinated hepatic lipid uptake/biosynthesis is balanced by the adipose depots’ capacity to store excess energy, supporting lipid repartitioning away from the liver. The results substantiate the adipose tissue expandability hypothesis and delineate molecular features underlying an MHO-like phenotype in Göttingen Minipigs. Future studies should identify regulatory factors of adipose plasticity and mechanisms enabling protection from metabolic disturbances, and assess longer-term dietary exposure.

• Duration and progression: The authors note they cannot rule out that longer-term FFC diet/obesity might eventually lead to adverse metabolic responses or steatosis. • Scope of inference: Gene expression and correlation analyses are observational and do not establish causality. • Sample considerations: A small number of adipose samples were excluded due to RNA quality; overall group sizes were modest (SD n=7, FFC n=14, FFCDIA n=8). • Species differences: Findings in Göttingen Minipigs may not fully generalize to humans given species-specific lipid metabolism (e.g., pig liver de novo lipogenesis differs from humans/rodents). • Inflammation assessment: Pro-inflammatory cytokine expression changes were limited to transcripts and histology in adipose tissue; broader immune profiling was not performed.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.