Medicine and Health

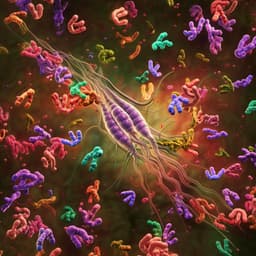

Nanoconstructs for theranostic application in cancer: Challenges and strategies to enhance the delivery

S. Mishra, T. Bhatt, et al.

Delve into the promising world of nanoconstructs for targeted cancer therapy! This innovative review by Shivani Mishra, Tanvi Bhatt, Hitesh Kumar, Rupshee Jain, Satish Shilpi, and Vikas Jain uncovers the potential of nanoparticles and ligands in enhancing drug delivery efficacy, while also addressing the challenges of biocompatibility and distribution.

~3 min • Beginner • English

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.