Engineering and Technology

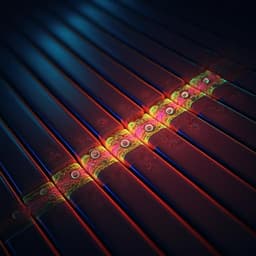

Low cost and massively parallel force spectroscopy with fluid loading on a chip

E. Akbari, M. Shahhosseini, et al.

Discover an innovative low-cost, high-throughput technique for single-molecule force spectroscopy, developed by Ehsan Akbari, Melika Shahhosseini, Ariel Robbins, Michael G. Poirier, Jonathan W. Song, and Carlos E. Castro. The FLO-Chip offers unparalleled versatility in multiplexed mechanical manipulation of molecules, allowing simultaneous testing of interactions at multiple loading rates.

~3 min • Beginner • English

Introduction

Single-molecule force spectroscopy provides critical insights in molecular biophysics but commonly relies on costly, specialized, and low-throughput instrumentation such as optical tweezers, magnetic tweezers, and AFM. Emerging multiplexed methods (centrifugal force microscopy, acoustic manipulation, nanophotonic trapping) reduce cost and increase throughput but still have limitations, including uniform loading across all interactions and the need for specialized setups. Hydrodynamic force spectroscopy offers simplicity and low cost but has been limited to single straight channels with one loading condition. The study aims to develop a cost-efficient, high-throughput, portable microfluidic platform that enables simultaneous application of multiple mechanical loading rates to many single-molecule constructs, broadening access to molecular force spectroscopy while retaining quantitative accuracy.

Literature Review

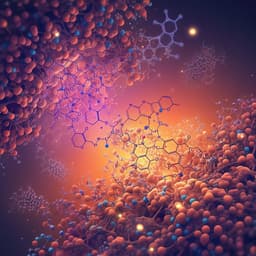

Prior work established single-molecule force spectroscopy via magnetic tweezers, AFM, and optical tweezers, enabling high-resolution measurements but with limited throughput and high cost. Recent methods (centrifugal force microscopy, acoustic bead manipulation, wide-range magnetic fields, nanophotonic trapping) improved multiplexing and reduced cost per experiment. Hydrodynamic force spectroscopy has demonstrated simple, low-cost multiplexed loading but historically used single channels and single loading rates. Dynamic force spectroscopy theory by Evans and Ritchie provides a framework to extract energy landscape parameters (koff, distance to transition state) from rupture-force versus loading-rate relationships. DNA mechanics via the worm-like chain model, and prior measurements of DIG–AntiDIG, biotin–streptavidin, and DNA duplex unzipping provide benchmarks for validation.

Methodology

FLO-Chip design: PDMS microfluidic devices fabricated via SU-8 photolithography and soft lithography were plasma-bonded to PEG/biotin-PEG functionalized coverslips. Chips contain serially connected microchannels of varying widths (e.g., 500–2500 µm at 120 µm height; or 250–1000 µm at 60 µm height) so that, at a given volumetric flow rate, narrower channels impose higher flow velocities and thus higher drag forces and loading rates. This allows simultaneous tests at multiple loading rates in a single chip. Molecular construct assembly: A 5745 bp dsDNA tether (≈1.9–1.95 µm contour) was prepared with biotin on one end (for coverslip anchoring via streptavidin) and a 30-nt ssDNA overhang on the other end for attaching the interaction of interest. Beads (≈2.2 µm diameter) functionalized with appropriate ligands (AntiDIG or streptavidin) were bound to the tethered construct. Hydrodynamic force application: A syringe pump controls volumetric flow rate Q. The drag force F on tethered beads produces tension on the tether and the interaction of interest. Equations and calibration: Force calibration used bead lateral fluctuations (equipartition) and geometry to determine F versus Q or average velocity V. The force was estimated using the equipartition theorem from the transverse mean-square displacement of the bead center and the tether length under tension; in-plane displacement provided the bead–tether geometry. Calibration was performed at low forces (<~1 pN) to satisfy sampling constraints. F scaled linearly with Q or V, with channel-width dependence matching expected velocity scaling. Example calibration slopes: 1.4 ± 0.2 pN·s·mm⁻¹ (first design) and 3.0 ± 0.2 pN·s·mm⁻¹ (multiplexed imaging design). Force-extension validation: Beads tethered by single dsDNA were subjected to force ramps to obtain average force–extension curves fit by the WLC model, providing persistence and contour lengths consistent with theory and tether length. Rupture force measurements: For DIG–AntiDIG, a DIG-modified oligo annealed to the tether overhang enabled bead attachment via AntiDIG. For biotin–streptavidin, biotin-modified oligos annealed to the tether overhang with streptavidin-coated beads provided serial connections; due to three serial biotin–streptavidin interactions, a modified Evans model (N interactions) was applied. Rupture events were recorded under linear force ramps at defined loading rates. Most-probable rupture forces were extracted from cumulative distributions and fit to Evans–Ritchie models to obtain koff and Δx. DNA unzipping assays: A short dsDNA region (9 or 18 bp, varying GC content) was placed between the tether and bead using sequential oligo assembly to position the unzipping junction and to control spacing from the bead. Unzipping rupture forces were measured under defined loading rates and buffer conditions (e.g., Mg²⁺ 5–20 mM). Multiplexed loading: A FLO-Chip variant permitted simultaneous imaging of four channel widths (250–1000 µm, 60 µm height), enabling simultaneous application of four loading rates. Automated image analysis in MATLAB identified single-tethered beads by bidirectional flow displacement, and detected rupture by bead disappearance (pixel area drop to zero) during ramped flow. Analysis throughput was ~5 minutes for ~4000 beads. Toehold-mediated strand displacement under force: Two configurations were designed: (i) strained toehold (force applied to toehold and branch migration domains) and (ii) strain-free toehold (force applied to branch migration domain only). Bead removal kinetics in the presence/absence of invader strand were monitored under 0.75–10 pN loads. Control measurements of DIG–AntiDIG dissociation alone established that bead removal was dominated by strand displacement in this force range; strand displacement rates were obtained by subtracting DIG–AntiDIG dissociation rates from total bead removal rates. Calibration/constraints: Calibration is valid for the specific bead diameter (2.2 ± 0.2 µm), tether length (~1.9 µm), and channel height (e.g., 120 µm). Changes in these require recalibration.

Key Findings

- FLO-Chip achieves low-cost (~$3 per PDMS chip) and high-throughput single-molecule force spectroscopy with up to ~4000 measurements per chip in ~2 hours, using conventional bright-field imaging and syringe pumps.

- Force and loading-rate ranges: approximately 0.1–100 pN and 10^-2–10^2 pN s^-1 (multiple channels provide simultaneous distinct loading rates).

- Force calibration: Linear F–Q (or F–V) relationships with channel-width scaling as expected. Example slopes: 1.4 ± 0.2 pN·s·mm^-1 (first design) and 3.0 ± 0.2 pN·s·mm^-1 (multiplexed design).

- dsDNA force–extension validation: WLC fits yielded persistence length 56 ± 8 nm and contour length 1.8 ± 0.1 µm for the 5745 bp tether, consistent with expected ~1.95 µm.

- DIG–AntiDIG rupture forces increased with loading rate: 25.9 ± 0.2 pN (0.5 pN s^-1), 33.2 ± 0.3 pN (1.5 pN s^-1), 37.2 ± 0.7 pN (5.0 pN s^-1), consistent with AFM and acoustic force spectroscopy reports. Evans–Ritchie fits gave koff = 4.0 ± 1.4 × 10^-1 s^-1 and Δx = 0.76 ± 0.05 nm; rupture distributions were independent of channel width for the same loading rate.

- Biotin–streptavidin (three serial bonds) showed rate-dependent rupture; fits to the N-serial-bond Evans model yielded koff = 4.7 ± 2.6 × 10^-1 s^-1 and Δx = 0.95 ± 0.02 nm. Projected single-bond rupture forces versus loading rate agreed broadly with literature; Δx was slightly larger than some reports, potentially due to force-loading geometry and the elastic tether.

- DNA unzipping (18 bp): At 0.19 pN s^-1 in 5 mM Mg²⁺, most-probable rupture forces increased with GC content: 8.3 ± 0.6 pN (33% GC), 10.2 ± 0.6 pN (61% GC), 11.6 ± 0.3 pN (83% GC), consistent with prior values (12–14 pN for 83% GC).

- DNA unzipping (9 bp, 78% GC): Most-probable rupture forces increased with loading rate: 6.5 ± 0.2 pN (0.2 pN s^-1), 7.5 ± 0.4 pN (0.6 pN s^-1), 7.8 ± 0.2 pN (1.9 pN s^-1); loading-rate dependence extrapolated close to prior hairpin data. Fits yielded Δx = 6.2 ± 0.4 nm (with reported koff consistent in order with literature for similar hairpins).

- Ionic effects: Increasing Mg²⁺ from 5 mM to 20 mM at 0.2 pN s^-1 increased 9 bp unzipping most-probable force from 6.5 ± 0.2 pN to 8.0 ± 0.3 pN, consistent with increased duplex stability.

- Massively parallel multiplexing: A four-channel, single-field-of-view chip enabled simultaneous loading rates (e.g., 2.5, 3.3, 5.0, 10 pN s^-1 for 1000, 750, 500, 250 µm channels). Automated analysis processed ~4000 beads in ~5 minutes.

- Toehold-mediated strand displacement under force: In the strained-toehold configuration, rates modestly increased between ~0.75–5 pN and plateaued from 5–10 pN. In the strain-free toehold configuration, rates were force-independent below ~5 pN but increased by over an order of magnitude from 5 to 10 pN.

Discussion

FLO-Chip provides quantitative, high-throughput single-molecule force spectroscopy using simple microfluidic flow to apply controlled forces, achieving results that agree with established techniques. The platform overcomes key limitations in throughput by testing multiple loading rates on a single chip via serial channels of varying widths and by automating bead selection and rupture detection. Validation against dsDNA elasticity and known receptor–ligand pairs (DIG–AntiDIG, biotin–streptavidin) establishes measurement fidelity, including extraction of Evans–Ritchie energy landscape parameters. Application to DNA duplex unzipping demonstrates sensitivity to sequence (GC content), loading rate, and ionic strength. The ability to monitor kinetics of toehold-mediated strand displacement under force reveals distinct force dependences depending on whether the toehold is strained, yielding mechanistic insights into how force modulates toehold hybridization, branch migration, and incumbent strand detachment. Collectively, FLO-Chip expands access to force spectroscopy by reducing cost and complexity while enabling massively parallel measurements across a wide range of loads.

Conclusion

The study introduces FLO-Chip, a low-cost, portable microfluidic platform enabling massively parallel single-molecule force spectroscopy with multiplexed loading rates. The system reproduces canonical dsDNA mechanics, measures rupture forces and energy landscape parameters for DIG–AntiDIG and biotin–streptavidin consistent with prior techniques, and quantifies DNA unzipping forces with sensitivity to sequence and ionic conditions. FLO-Chip further enables mechanistic studies such as the force dependence of toehold-mediated strand displacement. Its simplicity, low per-chip cost, and compatibility with conventional microscopes make high-throughput force spectroscopy accessible to a broad range of laboratories and educational settings. Future work may include integrating higher-resolution imaging for even greater throughput, refining force-directionality control (e.g., streptavidin variants), expanding calibration to diverse bead sizes and tether lengths, and coupling with mobile microscopy for point-of-care applications.

Limitations

Calibration is specific to the experimental geometry and materials (bead diameter ~2.2 µm, tether length ~1.9 µm, channel height 60–120 µm); any changes require recalibration. Hydrodynamic force spectroscopy sacrifices high spatial and temporal resolution and rapid force modulation achievable with optical or acoustic methods. The biotin–streptavidin serial-bond configuration may alter the effective energy landscape due to elastic tethering and complex force-loading geometry (streptavidin tetravalency), contributing to slight discrepancies in Δx relative to some reports. Using biotin on both tether ends reduced experimental yield (~400 data points per chip) due to potential dual surface binding. Force estimates and loading-rate conversions rely on accurate bead-tracking and fluctuation analyses at low forces; deviations in sampling or bead–surface interactions could affect calibration.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.