Biology

Image-guided MALDI mass spectrometry for high-throughput single-organelle characterization

D. C. Castro, Y. R. Xie, et al.

Organelles are one of the smallest structural units that influence the functional, morphological and biochemical characteristics of different cell types. Chemical analysis of individual organelles is challenging due to their attoliter volumes, the wide dynamic range of analyte concentrations and the need for sophisticated isolation procedures, limiting understanding of their chemical heterogeneity. MS imaging has been used for cellular and some subcellular analyses but is constrained by throughput and spatial resolution for organelle measurements. Alternatively, isolated cells/organelles can be placed on a slide for subsequent MS, but prior single-organelle peptide assays were low throughput and hard to automate due to manual positioning. A recent enhancement scatters cells on slides, localizes them via fluorescence, and targets positions with MALDI MS to assay tens of thousands of cells. Here, the single-cell approach is adapted to single organelles, requiring improved object targeting, optimized analyte detection using high-resolution MS, and unsupervised data analysis to characterize organelle heterogeneity. Using MALDI FT-ICR MS, the authors simultaneously detect peptides and lipids in 0.5–2-µm dense-core vesicles (DCVs) and lucent vesicles (LVs) from Aplysia tissues. The workflow reveals subtypes of DCVs defined by distinct peptide content, identifies a peptide prohormone not previously known to localize within DCVs, and shows large content differences between DCVs and LVs. The method is extendable to multiple imaging modalities (including scanning electron microscopy) and instrumentation using a piezo linear stage and camera, enabling analysis of targets smaller than the wavelength of light.

Prior work includes MS imaging for cellular and limited subcellular discovery studies, though throughput and spatial resolution limit organelle measurements. Isolation-and-measurement approaches allowed peptide assays in individual organelles but were manual and low throughput. Single-cell MALDI workflows combining microscopy-based localization with image-guided targeting enabled tens of thousands of cells to be analyzed. Immunogold studies in Aplysia bag cell neurons showed differential packaging of peptides (N- vs C-terminal products) into distinct vesicle classes, suggesting heterogeneous cargo sorting; similar phenomena had not been demonstrated in other Aplysia cell types. Earlier biochemical work on AG granules suggested possible distinct packaging of certain prohormone N-terminal peptides. Lipidomics studies in Aplysia neurons identified phosphatidylcholines detectable by MALDI. Collectively, these studies motivate a high-throughput, label-free, single-organelle MALDI approach to uncover organelle-level chemical heterogeneity and compare morphologically distinct vesicle types.

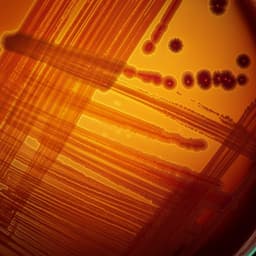

Sample source and isolation: Aplysia californica (150–200 g) were maintained at 14 °C. Animals were anesthetized with 333 mM MgCl2. For DCVs, the atrial gland (AG) was dissected into artificial seawater (ASW). Holocrine DCV secretion was induced by gentle trituration with a polypropylene Pasteur pipette to release intact DCVs. For LVs, the same procedure was applied to red hemiduct tissue. A volatile, isosmotic 500 mM ammonium acetate buffer (100 µl) was pre-spotted on ITO-coated glass. Then 50 µl vesicle-containing ASW was added (total 150 µl). Vesicles were allowed to sediment and adhere; the solution was aspirated and the surface rinsed with 500 mM ammonium acetate, leaving vesicles distributed across the slide. Each slide contained DCVs from three animals; three slides (technical replicates) were prepared. A total of 598 DCVs and 123 LVs were measured across the same biological replicates. Imaging and object recognition: Brightfield images were acquired (Zeiss Axio Imager M2, AxioCam ICc 5, ×10 objective, mosaic with 30% overlap; tiles stitched, exported as TIFF). Scanning electron microscopy (FEI Quanta FEG 450) was also used (10 kV, 10 µs dwell, 6.6 mm WD). Image processing utilized ImageJ and CellProfiler to selectively mask vesicles and generate a binary image with vesicles as foreground and background pixels set to zero. This mask was used with microMS software to translate pixel coordinates to MS stage coordinates. A 200-µm distance filter was applied to avoid targeting multiple vesicles with the 100-µm MALDI laser. The brightfield-based approach leverages vesicle pixel properties to identify DCVs without chemical labeling; axial resolution limits brightfield-based targeting to ~≥500 nm diameters, while SEM can extend targeting to nanometer-sized objects. Matrix application: 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid was applied by sublimation (glass sublimation apparatus at 150 °C for 8 min under vacuum), followed by recrystallization using 5% methanol in a sealed chamber at 85 °C for 1.5 min, then drying under nitrogen. MALDI FT-ICR MS: Analyses were performed on a Bruker SolariX XR 7T FT-ICR with APOLLO II MALDI/ESI source in positive mode over m/z 150–4,500. Acquisition at 1M points yielded resolution ~107,000 at m/z 535 and ~19,070 at m/z 3,922 (transient 0.721 s). Smartbeam-II UV laser in Ultra mode produced ~100-µm spot; each spectrum comprised two accumulations of 400 shots at 1,000 Hz. Stage coordinate lists were generated via microMS. Data preprocessing: Using Bruker Compass DataAnalysis and MATLAB 2018b. Internal calibration for AG peptide analyses used exact masses of AGPB1 [71–81] (m/z 1,221.6878), AGPA1 [22–34] (m/z 1,396.7225), AGPA1 [156–173] (m/z 1,908.8761), AGPA2 [33–69] (m/z 3,922.9478) and AGPB1 [85–118] (m/z 4,031.0053). Peak picking S/N ≥5, relative intensity threshold 0.01%, nonuniform bin width for alignment. For DCV peptide analyses, features were truncated at m/z 1,100; for LV/DCV lipid-based classification, m/z 500–1,100 features were used without internal peptide-based calibration. Cropped microscopy regions were matched to spectra for single-vesicle verification. Feature selection and statistics: CX matrix decomposition using statistical leverage scores selected top 200 features, with rank k=150 chosen based on reconstruction error (<25% of original dataset). K-means clustering (number of clusters by WCSS) partitioned DCVs; significant features per cluster were identified via Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Visualization used stacked violin plots of normalized intensities. LC-MS/MS peptide sequencing: AG peptide extracts (n=3) were prepared in acidified methanol, dried, and reconstituted in 0.1% FA. Separation used Bruker nanoElute with a C18 column (150 mm × 75 µm, 1.9 µm) at 300 nL/min, gradient 2–50% B over 120 min. MS was Bruker timsTOF Pro in PASEF mode (m/z 100–1,700; 1/K 0.6–1.6 Vs cm−2; 10 PASEF scans, 1.1 s cycle; CE 20–59 eV; dynamic exclusion 0.4 min). PEAKS Online performed de novo, DB, and PTM searches against Aplysia RefSeq (proteins ≤1,000 aa); tolerances: parent 20 ppm, fragment 0.03 Da; unspecific digest; PTMs included amidation, N-term/lysine acetylation, pyro-Glu (Q/E), phosphorylation (STY), and half-disulfide; 1% FDR at peptide level; proteins with -log10P > 20 and ≥1 unique peptide reported. Machine learning for vesicle classification: Gradient boosting trees classified DCVs vs LVs using features from m/z 500–1,100 with threefold validation. t-SNE (cosine distance) visualized separation. SHAP identified important features; 97 features with nonzero mean SHAP values were retained, with 36 putatively annotated (LIPID MAPS, 17 ppm tolerance). Models retrained on SHAP-selected features improved performance; feature contributions and P values (Wilcoxon rank-sum) were evaluated.

- High-throughput single-organelle MALDI FT-ICR MS profiled 598 DCVs and 123 LVs (0.5–2 µm diameter) from Aplysia tissues.

- DCVs: Over 50 mature full-length peptides were assigned (peptide mass fingerprinting) to eight known prohormones and one novel prohormone (Peptide D). Detected peptides included AGPA2 [36–69], AGPB1 [85–118], AGPA1 [117–152], AGPA1 [156–173] (or AGPB1 [205–222]), AGPA1 [22–34] (N-terminus), and AGPB1 [71–81] (N-terminus, truncated), yielding 39% coverage of AGPA1 and 28% coverage of AGPB1.

- Novel prohormone: Peptide D was identified by MALDI MS mass-match assignments (e.g., Peptide D [63–75] exact mass 1,670.7698, (M+H)+ 1,671.7776 with ppm error 1.23 ± 0.27; Peptide D [132–162] exact mass 3,432.7759, (M+H)+ 3,433.7831 with ppm error −0.05 ± 1.10) and validated via LC-MS/MS coverage.

- Simultaneous detection of lipids in single DCVs: three PCs were observed by mass-match—PC(18:1/16:0), PC(18:1e/16:0), PC(18:1e/18:1)—with assignment errors −1.62 ± 0.65 ppm, −2.59 ± 0.06 ppm, and −1.55 ± 0.21 ppm, respectively.

- Unsupervised analysis of DCVs using CX decomposition (top 200 features; k=150) and k-means revealed three DCV clusters. Defining features included N-terminal peptides (AGPB1 [71–81], AGPA1 [22–34]) and Peptide D [63–75] in Cluster 1, and multiple C-terminal peptides (AGPA1 [156–173], Peptide D [63–75], AGPB1 [85–118], Peptide D [132–162]) in Cluster 3, indicating differential packaging of N- vs C-terminal products into distinct DCV subpopulations.

- LVs vs DCVs lipid-based classification: Gradient boosting trees achieved 98.6 ± 0.78% accuracy (threefold validation) using m/z 500–1,100 features; t-SNE showed clear separation. SHAP identified 97 important features (36 annotated), highlighting sterol lipid species and other lipids (e.g., PIP3 27:7, LPA 22:2, SM 53:5:03, sterols such as ST 19:4;06;Glcα, ST 20:4;06;Glcα, ST 27:3:08;S) as discriminators. Representative spectra show notable differences across m/z 500–1,100 between LVs and DCVs.

- Morphological interpretation: Enrichment of sterol species in LVs correlates with membrane curvature phenomena and may underlie the cristae-like inner membrane structures observed in LVs, contrasting with single-membrane DCVs with dense cores.

The study addresses the challenge of characterizing chemical heterogeneity at the single-organelle level by introducing a label-free, image-guided MALDI FT-ICR MS workflow that combines brightfield or SEM-based targeting, high-resolution simultaneous peptide and lipid detection, and unsupervised/statistical machine learning analyses. This approach overcomes throughput and automation limitations of prior single-organelle assays and avoids the positioning and extraction complexities of capillary micro-sampling ESI methods. The detection of extensive prohormone processing products within DCVs, discovery of a novel prohormone (Peptide D), and identification of three distinct DCV subpopulations based on peptide content demonstrate functional heterogeneity in morphologically similar vesicles. The lipid-based classification cleanly differentiates LVs from DCVs and links lipid composition (notably sterol content) to membrane ultrastructure and curvature, providing biochemical explanations for observed morphological differences. The method’s adaptability to common freeware and instrumentation, and compatibility with multiple imaging modalities, positions it as a broadly applicable platform for subcellular studies and discovery of new organelle phenotypes.

This work establishes an image-guided, high-throughput MALDI FT-ICR MS platform for single-organelle analysis, enabling simultaneous peptide and lipid profiling of hundreds of intact vesicles. Key contributions include: (1) label-free targeting via image processing and microMS registration; (2) comprehensive peptide coverage from multiple AG prohormones in single DCVs; (3) discovery and validation of a novel prohormone (Peptide D); (4) revelation of three DCV subpopulations reflecting differential N- vs C-terminal peptide packaging; and (5) robust machine learning-based lipidomic discrimination between LVs and DCVs, implicating sterols in LV membrane architecture. The workflow is adaptable to other organelles and imaging modalities (including SEM for sub-500-nm targets). Future directions include applying the approach to additional organelle classes (e.g., microvesicles/exosomes), integrating higher-throughput targeting and data acquisition, expanding lipid and metabolite coverage, and correlating chemical phenotypes with functional readouts and ultrastructural imaging.

- Optical targeting limit: Brightfield-based object identification is constrained by the axial resolution of light microscopy to vesicles approximately ≥500 nm in diameter; targeting smaller objects requires nonoptical methods such as SEM.

- Sample preparation dependencies: Organelles must be isolated and adhered to ITO slides, which may introduce selection biases and potential loss of labile components despite efforts to minimize interference (e.g., avoiding paraformaldehyde).

- Spatial targeting constraints: A 100-µm MALDI spot necessitates a 200-µm distance filter between targets, limiting density and potentially reducing the number of analyzable vesicles per slide.

- Calibration and mass range: Classification analyses used m/z 500–1,100 without internal calibration and focus primarily on peptide and common lipid ranges (m/z 150–4,500), potentially missing very low/high m/z species.

- Putative identifications: Many lipid features were annotated by mass match within a ppm tolerance without MS/MS confirmation at the single-vesicle level.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.