Medicine and Health

High fat diet causes distinct aberrations in the testicular proteome

S. Jarvis, L. A. Gethings, et al.

Explore groundbreaking research revealing how a high-fat diet impacts male reproductive health by affecting the testicular proteome. Conducted by a team of experts, this study uncovers new insights and potential therapeutic targets for related health issues.

~3 min • Beginner • English

Introduction

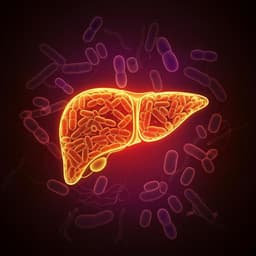

Obesity, driven by high-calorie diets and sedentary lifestyles, is associated with multiple adverse health outcomes and increasingly recognized effects on male reproductive health, including impaired semen parameters and higher rates of azoospermia. Mechanisms likely involve both central hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis changes and direct testicular effects on spermatogenesis and somatic cell function. High-fat (HF) diet models in rodents show reduced sperm count and motility, increased morphological abnormalities, altered androgen receptor expression, testicular inflammation, oxidative stress, sperm DNA damage, and potential transgenerational epigenetic effects. Despite these observations, key testicular targets and pathways remain insufficiently defined, with prior transcriptomic studies in mouse testis showing only modest changes and limited interpretability, particularly given transcriptional silencing during late spermatogenesis. The present study addresses this gap using a discovery proteomics approach to identify protein-level alterations and pathway perturbations in the testes of mice with diet-induced obesity, complemented by histology and validation by Western blotting and immunostaining.

Literature Review

Prior human and animal studies link higher BMI and diets rich in saturated fats with poorer semen quality, including dose-dependent reductions in sperm concentration and higher rates of azoospermia. In rodent HF diet models, male reproductive impairment manifests as reduced sperm volume and motility, increased morphological abnormalities, and heightened susceptibility to environmental insults. Mechanistic contributors include disturbances in the HPG axis, decreased androgen receptor expression, testicular inflammation, oxidative stress with sperm DNA damage, and effects extending to embryo quality and implantation. Epigenetic alterations to sperm with potential transgenerational consequences have also been reported. Transcriptomic analyses in mouse testes often show modest changes, limiting pathway insights. One related proteomic study in HF-fed rat testes, combined with long noncoding RNA arrays, highlighted cytoskeletal remodeling and oxidative stress as key features, motivating a protein-level discovery approach in the current work.

Methodology

Animal experiments: Male wild-type C57BL/6 mice were randomized at 11 weeks of age to either a high-fat (HF) diet (45% fat; Research Diets Cat# D1245) or standard normal chow (NC) (4.25% fat, RM3; Special Diet Services) and maintained until 32 weeks of age. Mice were housed under 12-h light/dark cycles with ad libitum water in specific-pathogen free facilities. Testes were isolated and flash frozen for analyses. Ethical approval and UK regulatory compliance were observed.

Human samples: Testicular biopsies were obtained from consented patients undergoing microsurgical testicular sperm extraction (mTESE) for histology and immunofluorescence (London REC 05/q0406/159).

Metabolic phenotyping: Body weight was measured weekly from 4 weeks of age. Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests (ipGTT) were performed at 8 and 27 weeks. After overnight fasting, mice received intraperitoneal glucose (2 mg/kg; 20% v/w). Blood glucose was sampled at 0, 15, 30, 60, and 120 minutes.

Histology and immunostaining: Testes (n=4 mice per group) were fixed in Bouin’s fluid or 10% neutral buffered formalin at 4 °C overnight, processed through graded ethanol and Histo-clear, and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections (5–6 µm) were stained with H&E. Stereological methods quantified spermatogenesis (Sertoli cell counts, meiotic index, post-meiotic round spermatids). Immunofluorescence and TUNEL assays were performed and visualized by Zeiss 510 confocal microscopy.

Western blotting: Whole testes were lysed in Tissue PE buffer with protease inhibitors. Protein (10 µg) was separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to PVDF membranes, blocked in 5% milk in PBS-T, and probed with primary antibodies to β-actin (1:5000), filamin A (1:1000), paraspeckle protein-1 (PSPC-1; 1:1000), and SPATA-20 (1:1000). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:2000) and chemiluminescence detection (Luminata Forte) were used.

Proteomic sample preparation: Frozen testis (40 mg) was homogenized with zirconium beads in Tris-HCl/DDT/SDS lysis buffer using a Precellys bead beater, heated (95 °C, 3 min), sonicated (5 min), and centrifuged. Protein concentration was measured by BCA assay. Samples (~1 mg/ml) in 0.1% RapiGest/50 mM ammonium bicarbonate were reduced (5 mM DTT, 60 °C, 30 min), alkylated (15 mM iodoacetamide, RT, dark, 30 min), and digested with trypsin (1:25 w/w, overnight, 37 °C). RapiGest was hydrolyzed with 0.5% TFA (37 °C, 20 min), followed by centrifugation; supernatants were diluted in 0.1% formic acid.

LC-MS configuration and data acquisition: Peptides were separated on a Waters ACQUITY M-Class system with a Symmetry C18 pre-column and HSS T3 C18 analytical column using a 3–40% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid gradient over 90 min at 300 nL/min (column at 35 °C). A Synapt G2-Si mass spectrometer operated in positive ESI ToF with ion mobility-assisted data-independent acquisition (LC-UDMSE). External calibration used NaCsI (m/z 50–1990); [Glu]-Fibrinopeptide B (200 fmol/µL) served as lock mass (sampled every 60 s).

Proteomic data processing: Progenesis QI for proteomics was used for peak picking, alignment, normalization, and relative quantification. Database searching used reviewed Mus musculus UniProt (16,738 entries; 2016_02). Design: two groups with data from 3 mice per group and 3 technical replicates per sample. Criteria: median abundance normalization; minimum 2-fold change and ANOVA p ≤ 0.05; identifications required detection in ≥2 biological and technical replicates; 1% FDR; quantification used unique peptides only.

Bioinformatics: GO term enrichment (biological/molecular processes) used PANTHER v11. Protein–protein interactions were assessed using STRING v10.5. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (QIAGEN) identified affected canonical pathways (Fisher’s exact test).

Key Findings

- HF diet induced obesity and insulin resistance: By 32 weeks, HF-fed mice weighed 46.77 ± 6.14 g vs 34.47 ± 2.85 g in NC (p < 0.0001), a ~12 g increase. Baseline fasting glucose at 8 weeks did not differ (NC 6.42 ± 1.04 mmol/L vs future HF 6.63 ± 0.79 mmol/L). At 27 weeks (after 16 weeks HF), fasting glucose was higher in HF (9.08 ± 2.22 mmol/L) vs NC (6.65 ± 1.58 mmol/L) (p = 0.011). ipGTT showed significantly impaired glucose tolerance in HF vs NC at both 8 and 27 weeks, with overall difference p < 0.0001.

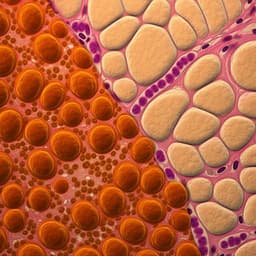

- Testicular histology: HF diet caused narrowing of seminiferous tubules (p < 0.05) and reductions in Sertoli cell numbers, meiotic index, and post-meiotic round spermatids. Apoptosis was not increased.

- Proteomics overview: 4,960 proteins identified at 1% FDR (≥1 peptide). Of these, 54 were unique to NC testes and 74 unique to HF testes. Among 4,074 proteins common to both conditions, 102 (2.2%) were differentially expressed (fold change ≥2; p ≤ 0.05; log2 fold change range −2.34 to +1.39), with 82% downregulated and 18% upregulated in HF.

- Notable protein changes: Structural protein filamin A (FLNA; blood–testis barrier), oxidative stress–related SPATA-20, lipid homeostasis regulators SREBP2 and APOA1, and paraspeckle component 1 (PSPC-1; interacts with androgen receptor) were significantly altered, with PSPC-1 notably downregulated.

- Validation: Western blotting and immunostaining confirmed and localized selected protein expression changes in both mouse and human testis specimens.

- Functional annotation: GO analysis revealed enrichment for processes related to meiosis, mitosis, chromosomal segregation, catabolism, protein transport, and cellular biogenesis. Network and pathway analyses indicated perturbations in cytoskeletal organization, oxidative stress responses, and lipid metabolism pathways under HF conditions.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that chronic high-fat feeding produces specific alterations in the testicular proteome alongside structural and cellular changes in the seminiferous epithelium. The downregulation of proteins involved in the blood–testis barrier (e.g., FLNA) and nuclear RNA regulation (PSPC-1) provides mechanistic clues to impaired Sertoli cell function and disrupted germ cell support, aligning with observed reductions in Sertoli cell number, meiotic index, and round spermatids. Altered abundance of oxidative stress–related (SPATA-20) and lipid metabolism regulators (SREBP2, APOA1) supports a model in which HF diet increases oxidative burden and dysregulates lipid homeostasis within the testis, processes known to affect spermatogenesis and sperm function. The predominance of downregulated proteins suggests broad suppression of key biological processes, including cell division and biogenesis, corroborated by GO enrichment. These proteomic and histological findings connect the metabolic phenotype of obesity/insulin resistance to specific testicular pathways and networks, offering targets that may underlie reduced male fertility associated with HF diets. Validation in mouse and human tissues enhances translational relevance.

Conclusion

Chronic high-fat diet in mice leads to obesity and insulin resistance and induces distinct testicular proteome changes, with 102 proteins significantly altered, predominantly downregulated. Affected proteins implicate the blood–testis barrier, oxidative stress handling, lipid metabolism, and nuclear RNA regulatory complexes (e.g., PSPC-1), and coincide with histological evidence of compromised spermatogenesis. The study provides a curated proteomic resource and pathway insights into how HF diet impairs male reproductive function. Future work should functionally interrogate key protein targets (e.g., FLNA, PSPC-1, SPATA-20, SREBP2, APOA1), assess causality in fertility outcomes, explore therapeutic modulation, and validate findings across additional cohorts and time points, including broader human studies.

Limitations

- Biological replication for proteomics was limited (n=3 mice per group), potentially affecting detection of smaller effect sizes.

- The study focuses on a mouse model; species differences may limit generalizability to humans despite supportive immunostaining in human biopsies.

- Emphasis on protein-level discovery with limited functional validation and without comprehensive assessment of downstream fertility outcomes.

- Cross-sectional endpoint after prolonged HF feeding; temporal dynamics of proteomic changes were not evaluated.

- RNA-level changes were not extensively profiled, and integration with other omics (e.g., metabolomics/epigenomics) was beyond scope.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.