Medicine and Health

Rapid discovery of self-assembling peptides with one-bead one-compound peptide library

P. Yang, Y. Li, et al.

The study addresses the challenge of rapidly discovering self-assembling short peptides from the vast combinatorial sequence space. While di- to hexapeptides can self-assemble via hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic, electrostatic, π–π, and van der Waals interactions, existing empirical design rules are limited and insufficient for broad applications. The authors propose leveraging the OBOC combinatorial peptide library coupled with a hydrophobicity-activated fluorophore (NBD) at the N-terminus to identify sequences that self-assemble in water by forming hydrophobic pockets that turn on NBD fluorescence. This enables an unbiased, scalable screening method to discover self-assembling motifs and materials.

Prior strategies to develop self-assembling peptides include: (1) empirical design based on natural amyloid fragments such as KLVFF (Aβ16–20) and NFGAIL (IAPP fragment); (2) computational screening predicting assembly propensity of short sequences (e.g., PFF, KYF, KFD); and (3) dynamic combinatorial peptide libraries via enzymatic condensation/hydrolysis enabling sequence exchange and discovery of diverse assemblies. Despite known trends (hydrophobicity, salt bridges, β-sheet formation), predictive rules remain empirical and inadequate, motivating an unbiased high-throughput experimental screen. The OBOC platform has historically enabled discovery of diverse ligands and is compatible with varied chemistries (natural/unnatural amino acids, cyclic/linear/branched constructs), suggesting suitability for discovering self-assembling peptides.

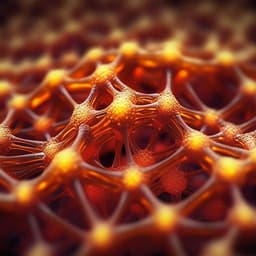

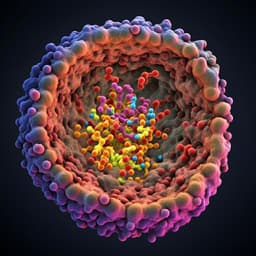

Screening principle: Peptides displayed on TentaGel S beads are N-terminally capped with nitro-1,2,3-benzoxadiazole (NBD), a fluorophore that is quenched in water but fluoresces in hydrophobic environments. Self-assembly of displayed peptides creates hydrophobic pockets near the N-terminus, turning on NBD fluorescence. Validation: Positive controls (KLVFF, NFGAIL, LIVGD) and a negative control (KAAGG) were synthesized on beads with NBD caps. In methanol both controls fluoresced; in water only self-assembling sequences (e.g., KLVFF) fluoresced, validating the assay. Library construction: An OBOC pentapeptide library X1X2X3X4X5 (X ∈ 19 amino acids; cysteine omitted) was synthesized via Fmoc SPPS on TentaGel S (0.31 mmol/g). Split–mix synthesis generated 19^5 diversity. After final Fmoc removal, bilayer beads were prepared (outer layer Fmoc-OSu, inner core (Boc)2O), then NBD-COOH was coupled to the N-terminus. Side chains were deprotected with TFA cocktail. Screening: Approximately 100,000–200,000 beads were screened in water under a fluorescence microscope. Positive beads exhibited strong fluorescence; negatives were dim/non-fluorescent. In one plate example, beads were immobilized on polystyrene dishes using DCM/DMF (1:4) and scanned by confocal microscopy; stitched images were quantified in MATLAB to obtain intensity distributions. Hit identification: Eight brightest positive beads and four dark beads were isolated and decoded by automated Edman sequencing. Peptides were resynthesized in soluble form (Wang resin, Fmoc SPPS), cleaved (95% TFA/2.5% H2O/2.5% EDT), purified by RP-HPLC, and characterized by MALDI-TOF-MS and LC-MS. Physicochemical characterization: Critical micelle concentrations (CMC) were measured; hydropathicity (GRAVY) computed via ProtParam. Morphologies were evaluated by TEM after assembling peptides (typically stock 5 mM in DMSO diluted 1:99 into water to 50 µM; or 30 mM in water with sonication). FT-IR (amide I band) assessed secondary structure; turbidity (transmittance 400–780 nm) assessed assembly. For FFVDF nanofibrils, powder X-ray diffraction and selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) determined lattice parameters and packing; a unit cell model was built (Cerius2). Time-dependent morphology and size were monitored by TEM and DLS (0 h, 4 h, 24 h; thermal annealing at 90 °C for 5 h tested stability). Circular dichroism (CD) monitored secondary structure evolution over 72 h. Cell studies: HeLa viability (CCK-8) assessed toxicity up to 200 µM. For imaging, peptide assemblies (40–50 µM) were doped with 3% N-terminally FITC-labeled peptide and incubated with live HeLa cells for 4 h, then imaged by confocal microscopy. Co-localization with LysoTracker and Hoechst assessed subcellular distribution. Uptake mechanisms were probed at 4 °C and with endocytosis inhibitors to determine clathrin/caveolae/micropinocytosis involvement.

- Screening outcomes: From ~100,000 beads screened by microscopy, eight intensely fluorescent positives and four dark negatives were sequenced. In a larger scan of 186,288 immobilized beads, 79 (~0.04%) had relative fluorescence ≥0.99 and 559 (~0.3%) ≥0.9, indicating a small fraction of strong self-assemblers in a random pentapeptide library.

- Identified self-assembling pentapeptides: FTISD, ITSVV, YFTEF, ISDNL, LDFPI, FAGFT, FGFDP, FFVDF. Composition analysis: 50% hydrophobic residues among the 40 residues (notably 11 Phe; also Ile, Val, Leu). Six peptides carry one acidic residue (Asp/Glu); two are neutral. None contain basic residues, contrasting with control KLVFF.

- Negative controls: RITWI, PLVKA, PFTTR, QIMRW (contain at least one basic residue), showed no detectable CMC and no assembly by TEM.

- CMC values for positives: 8.4–14.8 µM (FTISD 10.04; ITSVV 14.8; YFTEF 11.4; ISDNL 9.4; LDFPI 8.4; FAGFT 13.9; FGFDP 14.8; FFVDF 14.4 µM), supporting aqueous self-assembly propensity.

- Hydrophobicity: GRAVY values overlapped between positives and negatives (0.02–2.28 across many), and two negatives had negative GRAVY, indicating hydrophobicity alone cannot predict assembly.

- Structural characterization: At 30 mM in water, FFVDF formed a milky suspension with nanofibrils; YFTEF formed a hydrogel with fibrous network; PFTTR remained clear with no structures. FT-IR amide I bands for FFVDF and YFTEF narrowed and red-shifted to ~1630 cm−1 (anti-parallel β-sheet-like), versus 1641 cm−1 random coil for PFTTR. Turbidity at 20 µM: FFVDF lowest transmittance (e.g., 88% at 400 nm), YFTEF 98%, PFTTR 100%.

- FFVDF nanofibrils: Powder XRD and SAED indicated an orthorhombic lattice (a = 9.5 Å, b = 35.3 Å, c = 45.6 Å) with anti-parallel β-sheet dimers forming strong/weak interfaces; packing model constructed.

- Time-resolved morphology (50 µM in water with 1% DMSO unless noted): Initially, seven peptides formed nanoparticles (FTISD, ITSVV, YFTEF, ISDNL, LDFPI, FAGFT, FGFDP); FFVDF formed nanofibers at 0 and 4 h. Nanoparticles generally increased in size over 4 h (e.g., ITSVV from ~31 nm to ~300 nm; YFTEF 41 to 75 nm; FAGFT 10 to 15 nm), while LDFPI remained ~8 nm. After 24 h, all eight formed fibrils; fibrils remained morphologically stable after 90 °C annealing for 5 h. DLS corroborated time-dependent size increases.

- CD spectroscopy: Seven peptides showed stable spectra over 72 h; FFVDF exhibited decreasing Cotton effects, indicating reduced chirality in assemblies over time.

- Cell interactions and uptake (HeLa): All eight peptides non-toxic up to 200 µM. Subcellular distribution at 4 h (40–50 µM, 3% FITC-doped): LDFPI localized to nucleus and perinuclear regions (consistent with small ~8 nm size); YfTEF distributed in cytoplasm (granular/diffuse); ISDNL and FGFDP localized to lysosomes; ITSVV stained cell membrane with minor cytoplasmic signal; FTISD stained membrane and cytoplasm; FFVDF formed extracellular aggregates. Endocytic pathways: YFTEF clathrin-dependent; ISDNL caveolae-dependent and macropinocytosis; FGFDP both caveolae- and clathrin-dependent. Lysosomal trafficking: YFTEF retained ≥8 h; ISDNL and FGFDP escaped lysosomes at ~4 h and ~1.5 h, respectively.

The fluorescent-activation OBOC screen effectively addresses the challenge of discovering self-assembling peptides by directly reporting hydrophobic pocket formation upon assembly in water. The approach is unbiased with respect to sequence and rapidly identifies rare self-assemblers within large libraries. The discovery of eight pentapeptides with measurable CMCs and diverse morphologies validates the method and highlights that sequence context, charge distribution, and residue positioning, rather than hydrophobicity alone, govern assembly. Structural analyses (FT-IR, XRD/SAED) confirm β-sheet-rich assemblies, exemplified by FFVDF fibrils with defined orthorhombic packing. Biological assays demonstrate that several assemblies are biocompatible, interact with cells via distinct uptake pathways, and localize to different compartments (membrane, lysosome, cytoplasm, nucleus), underscoring their potential as modular building blocks for targeted delivery systems. The method’s simplicity, compatibility with automation, and adaptability to varying physicochemical conditions make it broadly relevant for materials discovery. Moreover, quantification of positive bead fractions provides insight into the frequency of self-assemblers in random pentapeptide space.

This work introduces a simple, robust NBD turn-on fluorescence assay integrated with OBOC libraries to rapidly discover self-assembling pentapeptides. Eight novel sequences were identified, characterized structurally and functionally, and shown to form nanoparticles or nanofibers with defined β-sheet content and diverse cellular behaviors, while exhibiting low cytotoxicity. The platform enables high-throughput, unbiased identification of self-assembling motifs and can be extended to co-assemblies, noncanonical amino acids, and libraries subjected to different environmental stimuli. Future research directions include: scaling and automating screens under varied conditions (pH, ionic strength, temperature, fields) to identify stimuli-responsive materials; designing libraries for heterotypic co-assembly; optimizing sequences for targeted intracellular trafficking or nuclear delivery; and in vivo evaluation of assemblies for drug and nucleic acid delivery.

- Library scope limited to pentapeptides composed of 19 canonical amino acids (cysteine excluded); results may not generalize to sequences with Cys or noncanonical residues.

- Only a small number of top-intensity beads (eight positives) were sequenced relative to library size; additional hits may display different properties.

- Hydrophobicity alone is insufficient to predict assembly; mechanistic determinants remain partly unresolved.

- Cellular studies were conducted in vitro in HeLa cells with short incubation times; in vivo behavior, biodistribution, and immunogenicity were not assessed.

- FITC labeling (3%) was assumed to minimally perturb assemblies and uptake; potential effects were not systematically quantified.

- Structural elucidation at atomic resolution was detailed for FFVDF; other sequences received less extensive structural analysis.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.