Biology

Magnetically controlled bacterial turbulence

K. Beppu and J. V. I. Timonen

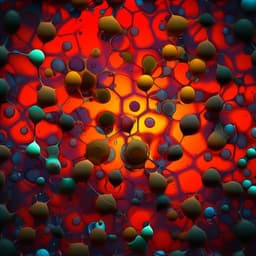

This groundbreaking research by K. Beppu and J. V. I. Timonen reveals how external magnetic fields can be utilized to control the swimming direction of *Bacillus subtilis* and induce active turbulence. With innovative methods involving superparamagnetic nanoparticles, this study uncovers the fascinating dynamics of hydrodynamic instability and bacterial behavior.

~3 min • Beginner • English

Introduction

Active matter systems display diverse collective behaviors, including swarming and flocking, driven by local energy conversion into motion. In fluid environments, active stresses generate flows that shape collective states; for extensile (pusher-type) swimmers, the Simha–Ramaswamy hydrodynamic instability prevents spontaneous long-range orientational order, giving rise to active turbulence with transient vortices and jets. While ubiquitous across biological and synthetic systems, active turbulence has been challenging to control, limiting understanding of its intrinsic properties. Previous control attempts have used geometric confinement or magnetically aligned liquid crystals, or required field-responsive/engineered organisms. This study asks whether uniform external torques can directly control the orientation and collective states of non-magnetic, rod-shaped bacteria in bulk, thereby tuning transitions between turbulent and ordered phases. The authors propose immersing Bacillus subtilis in a magnetizable (ferrofluid) medium so that an external magnetic field induces a nematic magnetic torque on bacterial bodies, enabling alignment and control of turbulence, and investigate the resulting structures, instabilities, and intrinsic length scales experimentally and via continuum theory.

Literature Review

The paper reviews how hydrodynamic instabilities in extensile active systems (e.g., bacteria, microtubule-kinesin assemblies) inhibit long-range order and produce active turbulence. It summarizes control strategies: geometric confinement stabilizing vortices and coherent flows; magnetically aligned liquid crystals streamlining living liquid crystal turbulence; and stimulus-responsive active matter (magnetotactic or photokinetic bacteria) that require specific species or engineering. It highlights the need for a general bulk control method applicable to non-magnetic agents. Prior work established the Simha–Ramaswamy instability, bend instabilities in active nematics, and scaling features of active turbulence; yet intrinsic properties and controllability remain unresolved due to turbulence’s self-sustaining nature.

Methodology

Experimental: Bacillus subtilis (strain 3610) were suspended in Terrific Broth (TB) mixed with PEG-stabilized ferrofluid (Ferrotec PBG300) at volume fractions ϕ = 0.02–0.10. Magnetic nanoparticles did not attach to bacteria; swimming speed reductions were ≤ ~20% at ϕ = 0.1. Uniform horizontal magnetic fields were applied using a Helmholtz/electromagnet coil setup; imaging at 30 fps with a 20× objective. Low-density samples (c0 ≈ 1–2 × 10^7 cells/cm^3) were observed in glass capillaries; high-density samples (c0 ≈ 6 × 10^10 cells/cm^3; ~20% v/v) were prepared as thin films ~60 μm high with a large air–liquid interface to ensure oxygenation, yielding quasi-2D dynamics near the interface. Individual trajectories were tracked by PTV (TrackMate) with preprocessing (background subtraction, contrast enhancement, median filtering, inversion), selection for ballistic motion, and smoothing over 10 frames. Collective velocity fields were obtained by PIV (PIVLab) with 16×16 px windows (~5.52 μm), Wiener2 denoising, and 1 s temporal smoothing. Local bacterial orientation fields were computed via structure-tensor analysis (ImageJ Orientation plugin), coarse-grained to PIV grid. Order parameters S = ⟨cos 2θ⟩ were computed for velocity and orientation. Orientation correlations C(Δr) = ⟨cos 2(θ(r+Δr) − θ(r))⟩ were measured parallel and perpendicular to B and fitted by G(Δr) = (1 − a) e^{−(Δr/ℓ)^b} + a to extract coherence lengths ℓ and order a; characteristic undulation half-wavelength λ was defined by the first local minimum of the correlation. Spatial velocity correlations C_Δr(Δr) and temporal correlations C(Δt) were analyzed to extract characteristic lengths and correlation times. Field pulses enabled on/off switching to probe instability growth and measure intrinsic wavelengths shortly after field removal (≤0.5 s).

Theory: A two-field continuum model couples fluid flow u(r,t) (2D Stokes with substrate friction α) to bacterial nematic orientation n(r,t). Fluid: −μ∇^2 u + ∇p + αu = −f0 ∇·(nn), with ∇·u = 0. Orientation dynamics: ∂_t n + (u·∇)n = D ∇^2 n + (I − nn)·(γE + W)·n − J_β (I − nn)·n, where E and W are strain and vorticity tensors, γ is a shape parameter (−1 ≤ γ ≤ 1; set γ = 0.9), D is orientational diffusion, and J_β encodes a nematic magnetic torque aligning bacteria with field direction B (|B|=1). Linear stability analysis about a nearly aligned state along B considers perturbations n_y ≪ 1 with wavevector along x (parallel to B), yielding growth rate σ(k) = f0 k^2 (1+γ)/[2(α+μ k^2)] − D k^2 − J_β. The fastest-growing wavenumber k_c = [−D_r + √(D_r^2 + 4 V D F)]/(2 D_r M) with F = f0(1+γ)/(2α), M = μ/α, V=1 (notation consistent with text), is independent of J_β; hence the characteristic undulation wavelength 2π/k_c is predicted independent of B. Parameter estimation: By matching measured PIV velocity fields to Stokes solutions driven by measured n(r,t) within 0.5 s after field-off, the optimal μ/α = 605 μm^2 and f0/α = 3820 μm^2 s^{-1} were found via minimizing Q = ⟨|u−v|^2/(|u||v|)⟩. Using μ ≈ 1 mPa·s, this gives α ≈ 2 × 10^{−3} Pa·s·μm and force dipole strength q ≈ 0.1 pN·μm from f0 = q c0 (c0 = 0.06 μm^{−3}). From the measured intrinsic half-wavelength λ0/2 ≈ 44.2 μm (λ0 ≈ 88.4 μm) at B = 0, D_r ≈ 221 μm^2 s^{−1} is inferred. The magnetic alignment strength is modeled as J_β = 2 Γ e1 B^2; using the slope of inverse orientation fluctuation versus B (0.347 mT^{−1}) at ϕ=0.1 and independently measured D_θ = 0.066 rad^2 s^{−1}, the transition field B_c from turbulence to stable nematic is predicted by J_β^c = (1/M)(√F − √D_r)^2, yielding B_c ≈ 21 mT.

Controls/notes: At the highest fields and long durations, slow nanoparticle chaining occurred but reversed upon field removal and lagged orientation changes; nanoparticles did not adhere to cells. Viscosity with ferrofluid at 27 °C is ~1 mPa·s at 10% in absence of field (from supplier).

Key Findings

- Uniform magnetic fields applied to non-magnetic, rod-shaped Bacillus subtilis in a magnetizable medium produce a nematic magnetic torque that aligns individual bacteria with the field direction, enabling bulk control of swimming direction.

- Dilute suspensions: Nematic order parameter S for swimming direction increases with B and approaches ~1 at φ = 0.1 under modest fields (~10 mT). Body orientation distributions follow P(θ) ∝ exp(−β sin^2 θ); inverse orientation fluctuations β increase approximately linearly with B.

- Dense suspensions: At low B, active turbulence persists; at higher B, bacterial orientations align nematically while the velocity field exhibits strong transverse (perpendicular to B) flows. Orientation order parameter approaches ~1, whereas velocity order parameter drops to ~0.3 under strong fields, indicating dominant transverse flow.

- Velocity magnitudes are significantly suppressed by strong B, especially in the component parallel to B; above ~20 mT, the perpendicular component dominates, indicating anisotropic transport controllable by B.

- Orientation correlations reveal coherence length along B is nearly independent of B, while perpendicular coherence increases with B. A characteristic undulating orientation structure forms with a half-wavelength λ/2 ≈ 22–23 μm (full λ ≈ 45 μm) at high fields; λ is nearly independent of B at strong fields.

- Rapid field-off experiments from a nematically aligned state show immediate growth of bending undulations with measured half-wavelength λ/2 = 44.2 μm within 0.5 s, directly evidencing the intrinsic hydrodynamic bend instability of extensile pushers and revealing a field-independent intrinsic length scale.

- Temporal velocity correlations show characteristic vortex lifetime τ ≈ 1 s at weak/intermediate B, increasing by ~2× in strong B due to persistent nematic order.

- Two-field continuum model (Stokes flow + nematic orientation with magnetic torque) reproduces observed flows from measured orientation fields and predicts a growth rate whose fastest-growing wavelength is independent of B, consistent with experiments.

- Parameter estimates from data-model matching: μ/α ≈ 605 μm^2, f0/α ≈ 3820 μm^2 s^{−1}; with μ ≈ 1 mPa·s, α ≈ 2 × 10^{−3} Pa·s·μm and bacterial force dipole strength q ≈ 0.1 pN·μm. From λ at B=0, D_r ≈ 221 μm^2 s^{−1}.

- Critical magnetic field for stabilizing nematic alignment predicted as B_c ≈ 21 mT via J_β = 2 Γ e1 B^2 and linear stability, matching the experimental onset of near-unity orientational order and sharp velocity suppression.

Discussion

The study demonstrates that externally generated, uniform magnetic torques can directly control the orientation and suppress or reshape turbulent flows in dense bacterial suspensions without requiring magnetotactic species or interfaces with aligned liquid crystals. By aligning bacteria nematically, the system transitions from active turbulence to an ordered state with characteristic transverse flows, revealing anisotropic transport properties tunable by the field. Switching the field off allows direct observation of the growth of the bend instability and measurement of its intrinsic wavelength, which is independent of magnetic field strength. The two-field continuum model captures these behaviors, predicting a field-independent fastest-growing mode and a critical alignment strength for stabilizing the nematic phase. This approach clarifies intrinsic length and time scales of active turbulence and enables quantitative extraction of physical parameters (active stress magnitude, substrate friction, orientational diffusion) that are typically difficult to access. The results advance understanding of non-equilibrium phase transitions in active matter and showcase magnetic fields as practical control knobs for programming collective states and transport in active fluids.

Conclusion

The authors show that non-magnetic Bacillus subtilis suspended in a magnetizable medium can be aligned and their collective dynamics controlled by uniform magnetic fields. In dilute suspensions, alignment leads to tunable nematic order of swimming directions. In dense suspensions, fields convert isotropic active turbulence into a nematically ordered phase accompanied by transverse flows; the undulating orientation structure has a characteristic length nearly independent of field strength. A minimal continuum model with magnetic torque quantitatively explains observations, predicting a field-independent instability wavelength and a critical field for stabilizing nematic order, consistent with experiments. Magnetic control simplifies complex turbulent states, enabling direct comparison of flow fields and intrinsic length scales between experiment and theory and permitting estimation of active stresses, friction, and orientational diffusivity. This general, bulk, and scalable control strategy opens pathways for programmable active materials and for probing dynamic critical phenomena in active turbulence; spatiotemporal magnetic field patterns could further enable advanced manipulation of individual and collective active states.

Limitations

- Parameter estimation uncertainties: The inferred orientational diffusion D_r from the measured instability wavelength (~221 μm^2 s^{-1}) is considerably larger than estimates based on elastic and drag coefficients (~30 μm^2 s^{-1}), likely reflecting approximations in dense-suspension elasticity and the need for dedicated rheology.

- Number density and environmental heterogeneity: Estimated active force dipole strength q depends on c0; vertical heterogeneity near the air–liquid interface and oxygen gradients in dense films may lead to over/underestimation.

- Nanoparticle chaining: At the highest fields and longest observation times, superparamagnetic nanoparticles form chains (albeit slowly and reversible upon field removal), which could perturb medium properties if sustained.

- Quasi-2D assumption: Dynamics are analyzed near the air–liquid interface where motion is quasi-2D; extension to fully 3D bulk may show differences.

- Species and medium dependence: While general in principle, quantitative parameters (e.g., Γ, e1, viscosity) are system-specific and may vary with bacterial species, ferrofluid formulation, and concentration.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.