Biology

First Peoples' knowledge leads scientists to reveal 'fairy circles' and termite linyji are linked in Australia

F. Walsh, G. K. Bidu, et al.

This groundbreaking research by Fiona Walsh and a team of Aboriginal and Western scientists uncovers the true origin of Australia's 'fairy circles', linking them to harvester termites through the rich tapestry of Indigenous knowledge. Discover how these ancient practices intertwine with ecological understandings.

~3 min • Beginner • English

Introduction

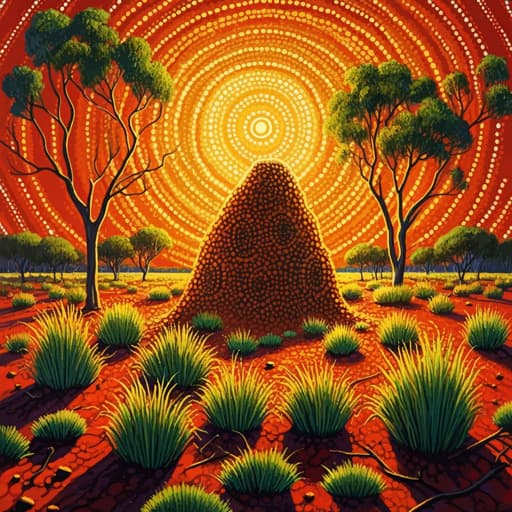

The study investigates the origin and ecological role of regularly spaced, bare circular patches in Australian arid grasslands, commonly termed 'fairy circles'. Earlier scientific work in Australia extrapolated theories from southern Africa, proposing that such patterns result from plant self-organization driven by hydrological-vegetation feedbacks. In contrast, Australian Aboriginal (First Peoples) knowledge—expressed through oral histories, terminology, ritual art and lived practice—links these circles (linyji/mingkirri) to harvester termite pavement nests. The authors aim to examine Aboriginal knowledge alongside scientific field surveys to test whether Australian fairy circles are termite pavements, and to explore how integrating knowledge systems clarifies ecosystem processes involving soil, water, grasses, fire, and termites.

Literature Review

- International and Australian debates on 'fairy circles' have proposed multiple causes: eroded termite mounds, microbes, toxic gases, Euphorbia toxins, insects (often termites), plant self-organization, and termite–plant interactions.

- In Namibia and Angola, circles are 2–24 m bare patches within grasslands; attention has increasingly focused on their regular spatial patterning.

- From 2016, Australian occurrences were reported and analyzed using remote sensing, modeling and limited excavations, with some studies arguing for self-organization without termite correlation. Press coverage amplified these interpretations.

- Aboriginal peoples' knowledge across desert Australia (Martu, Warlpiri, Anmatyerre, Pitjantjatjara and others) consistently associates the circles with harvester termites and encodes this in language, ceremonies, songlines, and artworks.

- Conflicting scientific evidence and the omission of Indigenous knowledge in prior work motivated this co-produced study to more deeply test termite involvement and the cultural-ecological context.

Methodology

Ethics and principles:

- Work guided by Martu cultural protocols; AIATSIS and International Society of Ethnobiology ethical guidelines; emphasis on recognition, collaboration, informed consent, attribution, and Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property (ICIP) respect. Prior Martu ethnographic work (1988–1990) with ethics approvals contributed foundational data.

Ethnographic methods:

- Compiled primary to tertiary sources on harvester termites and pavements across desert Aboriginal groups: recorded interviews, language dictionaries, published/unpublished narratives, photo/film archives, museum and gallery documentation, and peer-to-peer consultations with artists and knowledge holders.

- Built a database of termite-related content; triangulated sources and cross-checked across languages and geographies.

- Identified >120 Indigenous terms related to flying termites, pavements and their environments across 15 languages; documented 73 termite-related artworks by 34 artists and 42 distinct uses of termites/pavements.

- Mapped locations of records to show distribution across Western Australia, Northern Territory and South Australia.

Biophysical survey on Nyiyaparli country (East Pilbara, WA):

- Dates: 14–21 July 2021. Four of eight previously studied plots (near Newman) were resurveyed; each plot contained multiple bare circles.

- Excavations: 60 trenches (50 cm × 15 cm × 15 cm) within 24 circles (pavements); additional trenches in adjacent inter-pavement grassland next to 11 pavements. Trenches included center and radial positions on pavements; total of 29 m excavation.

- Tools: hand tools (mattock/crowbar), battery-powered saw and air blower to minimize structure damage; surfaces cleaned with air blower; all trenches photographed; backfilled after survey.

- Observations recorded presence/absence of termite indicators: chambers (open/frass/chaff), galleries, foraging tunnels, workers/soldiers; qualitative notes.

- Statistics: For five termite-related indicators, fitted binomial GLMs comparing occurrence probabilities on pavements vs adjacent areas, with site and interaction terms.

Biophysical exploration on Ngalia Warlpiri country (Newhaven Wildlife Sanctuary, NT):

- Dates: 1–2 May 2021. One pavement (~1.5 m diameter) examined; vertical cut to inspect internal structure; two north–south trenches connected by a tunnel under the pavement. Surrounding sandplain soils examined by hand.

- Water behavior test: applied ~50 L to observe ponding/infiltration on pavement vs adjacent sandplain.

Termite identification:

- Regional species considered: Drepanotermes perniger and D. rubriceps. All Newman pavements yielded D. perniger; Schedorhinotermes derosus found once under adjacent spinifex. Newhaven samples small; D. perniger present at both localities.

Aerial and remote observations:

- Used Google Earth and supplied helicopter/drone/ground records to detect pavement patterns and map broader distributions across arid WA, NT and SA. Identified overlaps with art/ethnographic records.

Key Findings

- Excavations unequivocally linked Australian 'fairy circles' to termite pavements:

- 60/60 trenches within 24 circles showed dense consolidated soils with a hard cap and termite nest architecture (chambers/galleries).

- 100% of on-pavement trenches revealed termite chambers; many with blackened plastered walls, frass-filled chambers, and stored grass chaff.

- Inter-pavement soils were unconsolidated, friable and lacked open chambers; foraging tunnels were present and radiated from pavements.

- Live Drepanotermes perniger were found in 41% of trenches.

- Statistical modeling showed significantly higher occurrence of frass-filled chambers and other termite indicators on pavements than in adjacent areas.

- Water dynamics:

- Consistent with Aboriginal knowledge, pavements ponded rainwater due to slight marginal sand banks and consolidated surfaces; water persisted longer on pavements than adjacent sandplain.

- Antiquity and landscape context:

- Eroded pavements observed in lower-lying Mulga shrublands suggest great antiquity (possibly Pleistocene), aligning with known millennia-scale persistence of earthen termitaria in arid zones.

- Indigenous knowledge and material culture:

- Identified 73 termite-related artworks by 34 desert artists; artworks and narratives depict regular pavement patterns, flying termite events, and associations with burning.

- Documented 42 uses of harvester termites and pavements, including seed threshing on/within pavements, food (alates) and sacred/ceremonial roles.

- Compiled >120 language terms across 15 languages for termites/pavements/environmental features.

- Spatial overlap:

- Satellite/aerial observations of pavements coincide with locations referenced in artworks and ethnographic records, including sites named Watanuma surrounded by pavements.

Discussion

The findings directly address the origin of Australia's regularly spaced bare circles: they are hard-capped, consolidated pavement nests occupied by harvester termites (Drepanotermes), not solely plant self-organization phenomena. Excavation evidence, termite identifications, and structural differences between pavements and adjacent soils corroborate Aboriginal knowledge that manyjurr live beneath linyji/mingkirri. Water ponding on pavements further validates Indigenous narratives and reveals underappreciated hydrological functions. These results reframe the Australian 'fairy circle' debate to integrate termites as key ecosystem engineers interacting with spinifex grasslands, soil consolidation, water redistribution, and Aboriginal burning and seed-processing practices. The co-learning approach demonstrates how First Peoples' deep-time observations generate testable hypotheses and enrich ecological understanding, improving the basis for land management and cultural continuity. Potential long-term feedbacks among termites, grasses, fire mosaics, and human use could have co-evolved, contributing to resource availability, food economies, and demographic patterns in the Holocene.

Conclusion

This study shows that Australian 'fairy circles' are termite pavement nests (linyji/mingkirri) of harvester termites, validating long-held Aboriginal knowledge through convergent scientific evidence from excavations, species identifications and hydrological observations. Indigenous art, language and practice encode extensive ecological information that, when engaged respectfully, advances ecosystem science and management. Future research should: deepen biophysical analyses of pavement hydrology and subsurface architecture (including deeper excavations and geophysical methods), quantify multi-scale interactions among termites, grasses, soils, rainfall and fire regimes, expand systematic aerial mapping of pavements across Australia, and strengthen ethnobiological and linguistic documentation in partnership with communities. Co-produced research and intergenerational knowledge transfer are essential to sustaining both cultural and biological diversity and to informing adaptive land stewardship under changing fire regimes and climates.

Limitations

- Mapping of authors' affiliations to specific individuals is incomplete in the provided text; some details are generalized.

- Art interpretation poses ethical and methodological challenges, especially for deceased artists; meanings can be context-dependent and partially inaccessible.

- Some ethnographic records are fragmented, posthumous, or affected by translation and species misidentification; not all knowledge elements are commensurate with scientific categories.

- Newhaven (NT) biophysical sample size was small; broader replication is needed.

- Excavations were shallow (15 cm) relative to potential nest depth; heavier machinery or geophysical tools are needed to resolve deep structures.

- Regional mapping is ongoing; records from New South Wales and Queensland were not comprehensively searched/mapped.

- Exact origins and age of pavements remain uncertain, likely extending into deep time (Jukurrpa).

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.