Psychology

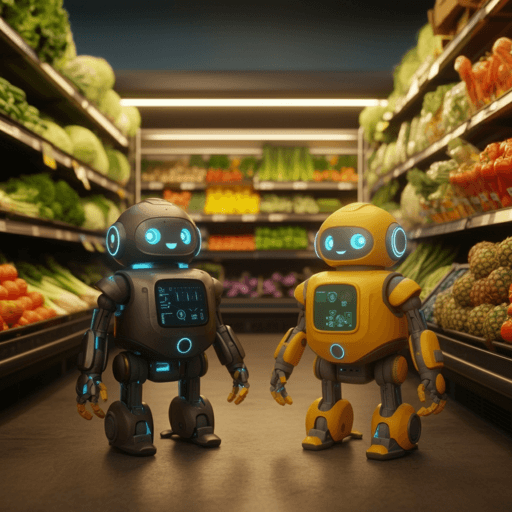

Exploring the Role of Sociability, Ownership, and Affinity for Technology in Shaping Acceptance and Intention to Use Personal Assistance Robots.

E. Roesler, S. Rudolph, et al.

Scenario-based online experiments reveal that people prefer low-sociability shopping robots and that affective affinity for technology predicts both acceptance and intention to use. When robots displayed high sociability, participants leaned toward more anthropomorphic forms—underscoring the importance of task-specific robot design. This research was conducted by Eileen Roesler, Sophie Rudolph, and Felix Wilhelm Siebert.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.