Engineering and Technology

A popcorn-inspired strategy for compounding graphene@NiFe₂O₄ flexible films for strong electromagnetic interference shielding and absorption

M. Liu, Z. Wang, et al.

Electromagnetic interference (EMI) is increasingly problematic as compact, high-density electronics proliferate, where conventional metal-based shielding films relying on reflection underperform, especially after mechanical deformation or corrosion. Thin, flexible, porous carbon-based composites (graphene, CNTs, MXenes) offer conductivity for shielding and micro/nanoporous structures for absorption, but realizing uniformly distributed magnetic nanoparticles within a highly conductive monolithic scaffold remains difficult. High-temperature graphitization or strong reductants that improve sp2 conjugation often cause nanoparticle sintering, agglomeration, or redox-induced denaturation, while simple physical mixing leads to agglomeration and poor distribution. Laser processing is promising but transient pulses induce blast effects, local heat accumulation, structural damage, and non-uniform nanoparticle growth. The authors ask how to regulate laser heat distribution to preserve conductive networks, avoid bursting/thermal accumulation, and achieve uniform, ultrafine magnetic nanoparticle loading within a 3D porous graphene scaffold to maximize absorption-dominated EMI shielding in thin films.

- Carbon-based and MXenes-based composites have shown promise due to high conductivity, porosity, flexibility, and corrosion resistance. However, methods to combine magnetic oxides without degrading conductivity are limited.

- NiFe₂O₄/rGO prepared by co-precipitation/hydrothermal growth on GO achieved ~38.2 dB EMI SE at 2 mm thickness with 35% nanoparticle occupancy (Kumar et al.).

- MXene/MWCNTs/SrFe₁₂O₁₉ films achieved 62.9 dB but conductivity decreased by ~80% compared with pristine MXene (Huang et al.), highlighting stability and porosity challenges.

- Laser-induced graphene (LIG) composites: Metal nanocrystals embedded in LIG (LIG-NiFe) via laser scribing of metal-salt-soaked wood suffered film discontinuity due to blast and pyrolysis-induced volume expansion (Han et al.). LIG@Fe₃O₄ films formed by laser processing polymer/metal-salt mixtures exhibited uniform particle loading but increased sheet resistance by ~100% due to network damage from simultaneous nanoparticle formation and laser blast/heat (Yu et al.).

- Overall, prior approaches struggle with nanoparticle agglomeration, damage to conductive networks, and trade-offs between conductivity and absorption. Few studies directly control laser heat distribution to ensure uniform nanoparticle size/loading and preserve conductive scaffolds.

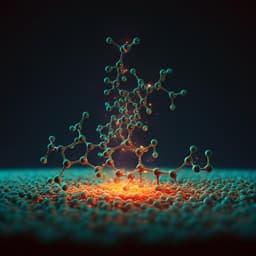

Concept and process: A “popcorn-making-mimic” strategy converts transient laser pulse energy into uniformly distributed heat by covering LIG with a GO lid that thermally reduces to rGO during processing. The GO lid confines and homogenizes heat, suppressing oxidation, bursting, and inhomogeneous thermal accumulation, enabling uniform nucleation/growth of ultrafine NiFe₂O₄ nanoparticles and preserving the 3D conductive LIG network.

Materials: Polyimide (PI) film (125 µm), NiCl₂·6H₂O, Fe(NO₃)₃·9H₂O, GO dispersion (10 mg g⁻¹, single-layer ≥99.5%, 5–8 µm lateral size), analytical-grade reagents.

Fabrication of LIG: One-step direct laser writing on PI (10 × 15 cm). Fiber laser, λ=1064 nm; defocus beam size 10 mm; scan speed 50 mm s⁻¹; scan pitch 0.01 mm; power 15% (4.22 W). Substrates cleaned with ethanol and DI water; PI taped to glass.

Fabrication of rGO/LIG@NiFe₂O₄: On a 4 × 4 cm LIG area, drop-cast 150 µL NiCl₂ solution (0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 1.0 M) and dry at 60 °C for 1 h. Mix 2.0 g GO dispersion (10 mg g⁻¹) with 10 mL Fe(NO₃)₃ solution at same concentration as NiCl₂; drop-cast 300 µL of the GO/Fe solution onto the Ni-loaded LIG and dry at 60 °C for 1 h. Laser process in ambient with fiber laser: defocus 10 mm, scan speed 250 mm s⁻¹, pitch 0.005 mm, power 6% (2.43 W). Samples labeled F-N-X (X = 0.3–1.0 M). A single-step co-drop option yields similar results; the two-step drop-cast aids inspection for voids. Control LIG@NiFe₂O₄ is prepared identically but without adding GO (no lid).

Characterization: Morphology by FE-SEM (SAPPHIRE SUPRA 55) and TEM/HRTEM (FEI Tecnai G2 F30); structure by XRD (10–80°, 5° min⁻¹) and Raman (Horiba LabRAM HR800); surface chemistry by XPS (Al-Kα, ESCAABSB 250Xi). Electrical properties by four-probe (MCP-T610). Surface area and porosity by BET; wettability by contact angle. Magnetic properties by VSM (bkt-4500z). EMI shielding in X-band (8.2–12.4 GHz) by VNA (PNA-N5244A), extracting S-parameters (S₁₁, S₂₁, S₂₂, S₁₂) and calculating SE_T, SE_R, SE_A, absorption ratio. Density determined gravimetrically using measured thickness and area. Nanoparticle size statistics from TEM (n=50) via Nano Measurer.

Finite element analysis (FEA): COMSOL Multiphysics 5.6 models heat and stress in rGO/LIG@NiFe₂O₄ vs LIG@NiFe₂O₄ under laser-induced heating. A Gaussian-distributed surface heat source (P₀, spot radius r_c, reflectivity R_c) with boundary at 293.15 K. rGO surface emissivity ~0.025; radiative losses included; heat conduction q = −K∇T. Thermal expansion ε_th = α(T−T_ref), stress σ=E(ε−ε_th). Substrate and NiFe₂O₄ particles treated as rigid in expansion but thermally conductive. Simulations include continuous 2.4 W heating for 1 s and pulsed 2 ns power, tracking maximum temperature and von Mises stress in rGO layers (excluding lid).

- Structure and morphology: The GO lid suppresses laser-induced bursting and uneven heating, preserving the 3D porous LIG architecture. rGO/LIG@NiFe₂O₄ shows uniform NiFe₂O₄ nanoparticles embedded on/within LIG with average size 3.63 ± 0.98 nm; composite thicknesses: ~67 µm (F-N-0.3), 67 µm (F-N-0.5), 70 µm (F-N-0.7), 73 µm (F-N-1), similar to pristine LIG (~71 µm).

- Crystallinity and composition: XRD confirms high-crystallinity, pure-phase NiFe₂O₄ (ICDD 01-089-4927) alongside LIG peaks; Raman shows reduced D-band intensity after GO→rGO transition. XPS identifies Ni²⁺ (Ni 2p₃/₂ 856.1 eV; 2p₁/₂ 873.8 eV; satellites 861.9, 880.8 eV) and Fe³⁺ (Fe 2p₃/₂ 711.5 eV; 2p₁/₂ 724.9 eV; satellites 716.6, 732.1 eV).

- Surface area/porosity: BET surface areas (m² g⁻¹): LIG 121.87; composites 164.71 (0.3 M), 146.69 (0.5 M), 149.66 (0.7 M), 131.2 (1.0 M). Pore volume only slightly reduced vs LIG, indicating preserved porous network with uniform loading.

- Electrical properties: LIG sheet resistance 6.58 Ω/□, conductivity 25.32 S cm⁻¹. rGO/LIG@NiFe₂O₄ sheet resistance (Ω/□)/conductivity (S cm⁻¹): 7.88/21.20 (0.3 M), 9.23/18.25 (0.5 M), 10.47/16.08 (0.7 M), 11.13/15.39 (1.0 M), corresponding to conductivity decreases of 16%, 28%, 36.5%, 39.2% vs LIG. Control LIG@NiFe₂O₄: 16.73 Ω/□, 11.95 S cm⁻¹ (−52.8% vs LIG), demonstrating the GO lid preserves the conductive network.

- Wettability: Contact angles (air): LIG 17°; LIG@NiFe₂O₄ 20.7°; rGO/LIG@NiFe₂O₄ 53.5°, indicating increased hydrophobicity beneficial for device protection.

- Thermal behavior: TGA/DSC shows NiFe₂O₄ promotes LIG combustion (lower onset), while the rGO lid retards combustion and smooths/splits pyrolysis peaks, consistent with smaller, more uniform nanoparticles and improved thermal stability during processing.

- Magnetic properties: Saturation magnetization Ms (emu g⁻¹): 1.88 (0.3 M), 2.84 (0.5 M), 3.32 (0.7 M), 4.60 (1.0 M). Coercivity Hc: 117, 119, 126, 129 Oe, indicating soft magnetic behavior that aids impedance matching and magnetic loss.

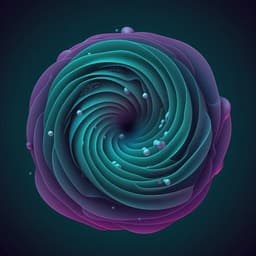

- EMI shielding (X-band, 8.2–12.4 GHz): • Max SE_T: LIG 25.2 dB; composites 29.5 (0.3 M), 34.3 (0.5 M), 36.0 (0.7 M), 33.3 dB (1.0 M). • Average SE_T over X-band: LIG 23.8 dB; composites 27.8, 32.6, 34.4, 31.8 dB (0.3–1.0 M). • Absorption-dominant: Max SE_A LIG 15.5 dB vs composite 25.6 dB (0.7 M). Average SE_R increases slightly (<10.5 dB vs LIG 8.6 dB) due to better impedance matching. • Absorption ratios: Max LIG 66.2%; max composite 75.2%. Average absorption efficiency: LIG 63.7% vs composite 69.5% across X-band. • Double-sided films (thickness ~166 µm): SE_T 51 dB and highest absorption 73.3% for rGO/LIG@NiFe₂O₄ (F-N-0.7), vs double-sided LIG SE_T 36 dB and 70.7% absorption; gains of +15 dB (SE_T) and +11 dB (SE_A). • Control LIG@NiFe₂O₄ (no GO lid): SE_T 27.6 dB, SE_A 17.4 dB, SE_R 10.2 dB, absorption 63%, confirming inferior performance without lid. • Absolute shielding effectiveness SSE/t up to 20906 dB cm² g⁻¹ with 75% absorption for a single-sided film.

- Mechanics and reliability: Composite is flexible and thin. Tensile strength increased by ~8.4 MPa vs LIG; maximum tensile strength up to 57.5 MPa; elongation at break >20% for both. GO lid enhances mass retention (>10% higher residual carbon after laser), improving structural integrity. After 10,000 bending cycles (diameter ~2 cm): sheet resistance change −16.4% (LIG) and +2.6% (composite). After 500 h at 85 °C/85% RH: sheet resistance changes 8.0% (LIG) and 2.3% (composite). LIG’s SE improved to ~32.5 dB after bending/aging (structural alteration), while composite’s SE and absorption remained essentially unchanged, indicating excellent stability.

- Finite element modeling: The rGO lid reduces peak temperatures and von Mises stress in underlying rGO layers and homogenizes temperature fields. Under pulsed 2 ns laser, the lid stores energy and releases it as a continuous heat source, moderating substrate temperature rise. Lower, more uniform thermal profiles correlate with uniform sub-10 nm nanoparticle sizes and preserved conductive networks.

The study addresses the long-standing incompatibility between achieving high graphitization/conductivity in porous graphene scaffolds and uniformly incorporating magnetic nanoparticles without agglomeration or network damage. By using a GO lid that transforms into rGO during laser processing, transient laser energy is redistributed into spatially uniform heat, suppressing blast effects and thermal hotspots. This thermal regulation preserves the 3D conductive LIG network and enables the homogeneous formation of ultrafine, highly crystalline NiFe₂O₄ nanoparticles, improving impedance matching and magnetic losses. Consequently, the composites deliver absorption-dominated EMI shielding with higher SE_T and absorption ratios at reduced thickness, outperforming both pristine LIG and conventionally laser-prepared LIG@NiFe₂O₄. Mechanical robustness and environmental reliability further validate suitability for practical electronics where bending and harsh climates are common. Finite element simulations elucidate the mechanism by showing reduced temperature/stress and more uniform heat distribution with the lid, which also explains the narrower nanoparticle size distribution. The approach exemplifies how microthermal environment engineering during laser processing can optimize multifunctional nanocomposites for EMI shielding and potentially other applications requiring uniform nanoparticle integration within conductive porous frameworks.

A popcorn-inspired, GO-lid-assisted laser strategy was developed to fabricate rGO/LIG@NiFe₂O₄ composite films with uniform sub-10 nm magnetic nanoparticles embedded in a preserved, highly conductive 3D graphene network. The films achieve absorption-dominant EMI shielding with SE_T up to 36 dB at ~70 µm (single-sided) and 51 dB at ~166 µm (double-sided), absorption ratios up to 75% (single-sided) and 73% (double-sided), and an absolute shielding effectiveness SSE/t of 20906 dB cm² g⁻¹. The composites exhibit enhanced tensile strength (up to 57.5 MPa), excellent flexibility, and stability under 10,000 bending cycles and 500 h of 85 °C/85% RH aging. The methodology offers scalability (via laser power/beam size) and tunability (via precursor concentration and processing parameters), providing a general paradigm for engineering sophisticated porous nanocomposites for EMI shielding and other applications. Future work can explore broader precursor chemistries, optimization for other frequency bands, scale-up with higher-throughput laser systems, and integration into device-level architectures.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.