Psychology

When the antidote is the poison: Investigating the relationship between people’s social media usage and loneliness when face-to-face communication is restricted

D. Jütte, T. Hennig-thurau, et al.

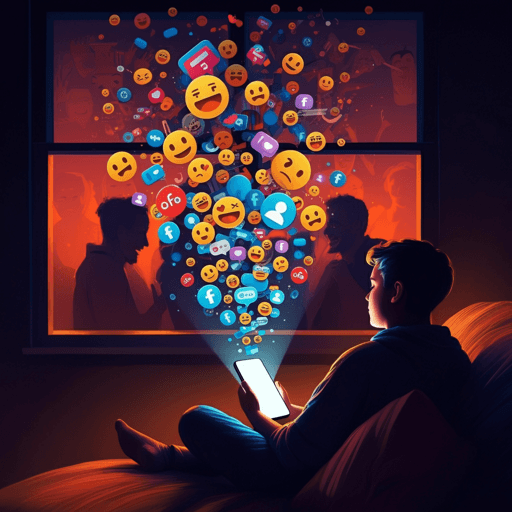

When lockdowns cut off face-to-face contact, this longitudinal study finds that greater social media use was associated with increased—not decreased—loneliness. Using German panel data from before and during the initial lockdown, the research conducted by David Jütte, Thorsten Hennig-Thurau, Gerrit Cziehso, and Henrik Sattler reveals a “social media paradox” and notes that richer digital media (e.g., video chats) can soften this effect.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.