Environmental Studies and Forestry

Using a co-created transdisciplinary approach to explore the complexity of air pollution in informal settlements

S. E. West, C. J. Bowyer, et al.

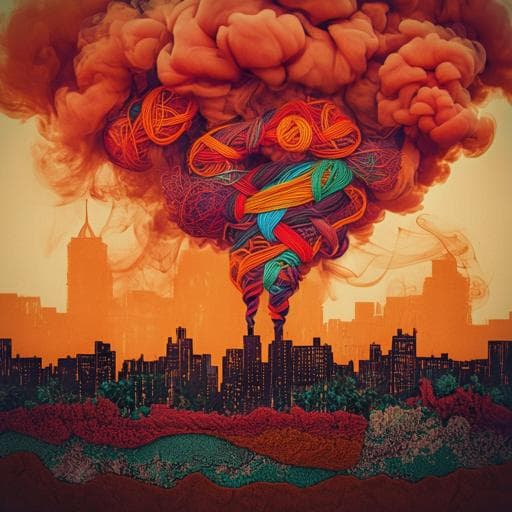

The study addresses how to design effective, context-relevant solutions to air pollution in Nairobi’s informal settlements by centering local knowledge and priorities. Air pollution is a leading environmental health risk globally and in African informal settlements, where exposures are elevated due to proximity to industry and roads, overcrowded housing, and reliance on solid fuels. Conventional top-down interventions (e.g., cleaner cookstoves) have shown mixed health outcomes, partly because they neglect local perceptions, practices, and competing livelihood concerns. The authors propose a transdisciplinary, co-created approach using arts and humanities methods to integrate scientific and community knowledge, address power differentials, and open new spaces for dialogue and problem-solving. The AIR Network project aims to build a nuanced understanding of community experiences and perceptions of air pollution in Mukuru and to co-develop context-appropriate solutions with residents and stakeholders.

The paper situates its approach within medical and health humanities and transdisciplinary research, emphasizing co-production and integration of diverse knowledge systems. Prior research in Nairobi’s informal settlements highlights high PM2.5 exposures and the importance of understanding perceptions for effective interventions. Participatory and citizen-science efforts have mapped exposures and engaged community champions, but arts and humanities methods have rarely been central to air pollution research in this context. The authors draw on literature advocating participatory, creative, and playful methods to capture experiences not easily verbalized, empower marginalized groups, and facilitate collaborative solution-finding. They also note calls for integrated approaches that bridge household air pollution and broader environmental health domains (e.g., WaSH), given overlapping determinants and affected populations.

Study location: Mukuru (Kwa Njenga, Kwa Reuben, Viwandani) in Nairobi, Kenya, home to ~100,000 households living in overcrowded, poorly serviced conditions with documented respiratory and cardiovascular health burdens.

Study approach: A transdisciplinary, co-created design placed creative, participatory methods at the core. A 4-day inception workshop (January 2018, Nairobi) convened Kenyan and international researchers (arts/humanities, social/natural sciences), community representatives (artists, teachers, health workers, prior project champions), and policymakers. Residents were positioned as co-researchers, establishing ground rules and co-developing four mini-projects aligned to priorities: (MP1) Raising awareness; (MP2) Action against air pollution; (MP3) Engaging with industry; (MP4) Prioritizing policies. Each combined data collection and dissemination.

Data collection and analysis: Multiple qualitative and creative methods were co-designed and implemented. At project end, representatives synthesized emerging themes across mini-projects.

-

Interviews: Five female community representatives conducted nine semi-structured, narrative-style interviews (August 2019) after training in narrative techniques and informed consent. Languages: English, Swahili, Sheng; guides/forms in English and Swahili. Purposive sampling targeted diverse perspectives: politician, doctor, researcher, teacher, community health visitor, cook, community volunteer, factory worker, car washer (3 men, 6 women). Two interviewees lived outside Mukuru (doctor, researcher). Transcripts (Swahili/Sheng translated to English) were coded by a single researcher in NVivo using Mind Maps for sources, effects, and solutions, documenting primary responses and contrary views.

-

Storytelling: Employed for engagement and sense-making. Digital storytelling (2–3 min voiceover-photo narratives) was produced by community members; schoolchildren created drawn/written stories; and two narrative pieces about air pollution and lung health were devised and performed during a week-long workshop (September 2018) alongside forum theatre.

-

Participatory mapping: Co-developed with Wajukuu Arts to create large, locally meaningful area maps of Kwa Reuben, Kwa Njenga, and Viwandani. On-street rapid mapping engaged passers-by (>500 residents), who placed stickers at perceived air pollution hotspots and provided source, reduction ideas, responsible actors, and demographics.

-

Theatre: Interactive participation methods—forum theatre (behavior-focused with community audiences) and legislative theatre (policy/system-focused with decision-makers)—were created in a week-long process (September 2018) using participants’ personal stories. Legislative performances were followed by a workshop (~40 participants, including local-to-county policy makers across Environmental Protection, Health, Waste Management, Urban Planning) to discuss and agree actions.

-

Music: Community musicians/filmmakers created original works (e.g., ‘Mazingira’ by Mukuru Kingz) reflecting community views. Dissemination included national radio/TV, live performances (Hood2Hood festival, World Environment Day), and YouTube.

-

Hood2Hood festival: One-day neighborhood festival (September 2018) at a local football ground combined stage presentations (stories, theatre, music) with interactive, playful activities (e.g., bean-counter boards on causes and responsibility), murals, and children’s engagement, reaching a broad audience (from young children to adults). Approximately 701 counters were placed by ~230 residents on the cause board.

-

Attribution: Creative contributors were credited to respect rights and support ownership.

Ethics: Approved by the University of York Environment and Geography Ethics Committee; informed consent obtained. Data availability: interview data not publicly available; other data in article.

- Perceptions of sources: Interviews identified poor drainage/sewage smells, cooking/heating stoves, burning household waste, smoking, dust, and industrial emissions as air pollution sources, with some contrary views (e.g., some advocating more waste burning to clean the environment).

- Quantified community perceptions (Hood2Hood bean-board): Of 701 counters (~230 residents), perceived main sources were industry 45%, drainage 24%, waste burning 17%, dust 8%, vehicle emissions 4%, and cooking 2%.

- Spatial hotspots (participatory mapping): Residents marked hotspots along the river, near rubbish dumps, and around certain factories; few dots were placed on homes, indicating a tendency to frame air pollution as outdoor/industrial/transport rather than household sources.

- Children’s perspectives: Schoolchildren’s stories prominently featured cookstove smoke, followed by vehicles and smoking, likely reflecting higher time spent indoors and proximity to cooking.

- Sensory framing: Residents defined air pollution through smells, sights, and sounds; carbon monoxide was an exception (invisible/odourless) yet frequently cited, likely reflecting public risk messaging and acute symptom awareness.

- Neighbourhood halo: Some perceived air pollution as worse in Nairobi city center than in Mukuru, illustrating localized normalization of risk.

- Knowledge change: Community researchers reported learning about multiple sources and indoor air pollution (“…not only is air pollution outside but it is also inside”).

- Responsibility for solutions (Hood2Hood bean-board): 56% of responses placed responsibility on individuals; 18% on the local community; 18% on county government; 8% on national government. Comments included perceptions of government inaction.

- Community-led solutions (multiple methods): Individual actions (maintain sanitation, burn garbage away from homes, stop smoking in streets, report issues to chiefs), landlord/structure-owner roles (e.g., windows, enforcement), and systemic/policy actions (community education on waste, more toilets, road maintenance/tarmacking, improved electricity, stricter industrial regulation/NEMA oversight, chimney filters/height, better firefighting service delivery, job creation to reduce reliance on local industries, protective equipment and stronger labour contracts with union involvement). Barriers included perceived government inaction and limited resident agency.

- Theatre outcomes: Legislative theatre revealed the practical difficulties of workplace and service-system reforms; attempts at worker-led improvements met resistance (e.g., risk of being fired), underscoring the need for policy-level change. Firefighting service gaps exacerbated pollution and risk.

- Broader systemic issues: Discussions expanded beyond air pollution to unemployment, inadequate water/sanitation, infrastructure deficits, and limited agency—highlighting interconnected challenges and the need for integrated solutions.

- Reach and engagement: Creative outputs (e.g., ‘Mazingira’) achieved broad dissemination (national media; YouTube; festivals), creating new spaces for dialogue within and beyond the community.

The transdisciplinary, co-created approach effectively surfaced nuanced, sometimes conflicting community perceptions of air pollution and responsibility for solutions. By embedding creative and participatory methods, the study captured sensory, situated understandings that standard surveys may miss, revealed the normalization of certain risks, and highlighted indoor versus outdoor perception gaps. These insights directly address the research aim of understanding how air pollution is perceived in Mukuru and inform why some top-down interventions falter: residents often prioritize visible, odorous, and outdoor industrial/drainage sources, while indoor cooking emissions may be under-recognized by adults.

The methods also generated actionable, community-derived solutions spanning individual behaviors, landlord practices, and systemic/policy interventions. Theatre and mapping clarified where power resides and the practical challenges of change, emphasizing the necessity of policy enforcement, infrastructure investment, and job creation alongside behavior change. The approach catalyzed knowledge exchange and skill-building among residents and researchers, helping bridge scientific and lay knowledge and creating platforms for broader engagement (e.g., festivals, music, media). Overall, findings underscore that air pollution cannot be meaningfully addressed in isolation from intertwined urban challenges (WaSH, labour, infrastructure), supporting calls for integrated, systems-oriented interventions aligned with the SDGs.

Co-created, transdisciplinary research integrating qualitative, participatory, and creative arts/humanities methods yielded a richer, more holistic understanding of air pollution perceptions and experiences in Mukuru and opened new avenues for dialogue, engagement, and solution generation. The study demonstrates that such approaches can uncover overlooked issues (e.g., drainage-related odors, occupational exposures), reconcile divergent viewpoints, and better target interventions to community concerns while building capacities and partnerships.

Future research should: employ transdisciplinary teams; integrate creative methods to bridge knowledge systems; provide space for multi-level stakeholder deliberation; and adopt systems thinking that connects air quality with water, sanitation, infrastructure, and livelihoods. These strategies can enhance the cultural relevance, sustainability, and effectiveness of interventions and support progress toward the SDGs.

- Breadth over depth: Using many methods constrained the depth of analysis by conventional disciplinary standards, though triangulation provided a broader understanding.

- Power and expectations: Co-creation required sharing control and managing participant expectations within funding/time limits.

- Time and resources: Significant time was needed for meaningful engagement; limited project duration constrained trust-building with surrounding industries.

- Logistics: Remote collaboration across time zones posed challenges, mitigated by regular communication (WhatsApp/email).

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.