Economics

Urban land expansion: the role of population and economic growth for 300+ cities

R. Mahtta, M. Fragkias, et al.

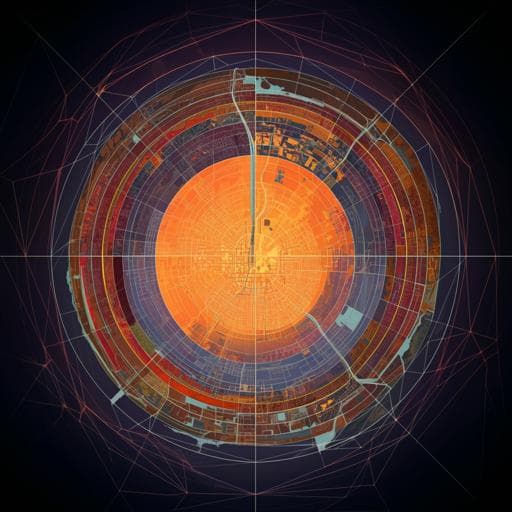

The paper investigates what drives urban land expansion (ULE) across cities worldwide, focusing on the relative roles of urban population growth and economic growth (GDP per capita). Urbanization involves both demographic growth and physical land change, with significant environmental and sustainability implications. Prior work often centers on single cities or regions and rarely examines global patterns over time, especially in developing regions where most future urban growth will occur. The authors pose the central question: What matters more for ULE under different geographic, development, and institutional contexts—population or GDP growth? They address: (1) city-scale patterns of population growth, economic growth, and ULE across world regions for 2000–2014; (2) whether population or economic growth drives ULE more; and (3) how their relative importance changes across regions, national income levels, and governance settings. Grounded in urban scaling theory, they formulate a growth accounting framework that decomposes ULE into components attributable to population growth and gross metropolitan product growth, and explicitly test these drivers across 300+ cities over 1970–2000 and 2000–2014, also considering governance as a mediating factor.

Existing studies of ULE typically focus on individual cities, single countries, or regions, with only a few global analyses that use a single time slice or country-scale GDP data. Research shows multiple determinants of ULE (e.g., topography, land suitability, climate, population), with demographic and economic growth often primary drivers, aligning with urban economics (land demand shifts with population and income) and urban scaling frameworks (systematic relationships between population, wealth, and land area). Local policies (zoning, floor area ratios, infrastructure subsidies, FDI) also influence ULE. However, most empirical work emphasizes Europe, North America, and China, creating a mismatch with projected urban growth concentrated in developing and least developed countries. While urbanization and national income are strongly correlated, countries with similar urbanization levels can have different incomes, potentially due to governance and institutional quality. Effective governance and rule of law are linked to service delivery, investment climate, infrastructure, and innovation, suggesting governance may mediate how population and income translate into land expansion. This study fills gaps by globally comparing the relative roles of population and GDP growth across contexts and introducing governance as a moderator.

Study design: Two periods were analyzed: pre-2000 (1970–2000) and post-2000 (2000–2014), selected because city-level GDP data are available only after 2000. Cities were analyzed at the city scale, with 251 cities pre-2000 (mainly >1 million population) and 363 cities post-2000 (478 initially identified, reduced to 363 after data merging). Data sources: ULE rates pre-2000 from a meta-analysis of city-based studies (Güneralp et al. 2020); post-2000 ULE from GHSL-derived built-up area change (Mahtta et al. 2019), focusing on outward expansion. Population: pre-2000 from the World Cities database (Henderson); post-2000 from Oxford Economics (Global Cities 2030). GDP: pre-2000 at country level except subnational for China, India, and the US; post-2000 city-level/proprietary (Oxford Economics) supplemented by national sources (e.g., China Statistical Yearbook, RBI) and Penn World Table v9.1 for other countries. ULE annual rates computed as ((urban area t1/urban area t0)^(1/n) − 1) × 100. Negative population and GDP per capita growth values were set to zero to reflect focus on expansion stages; ULE considered only positive rates. Cities were grouped into UN macro-regions, with Asia subdivided into China, India, Middle East, and Rest of Asia; small regions combined as "Others" in regressions. Statistical modeling: Ordinary least squares regressions with dependent variable log(ULE % annual). Independent variables: annual % growth in population and GDP per capita. Five model specifications: Model I baseline (population and GDP per capita growth); Models II–V add dummies for income group (World Bank LI, LMI, UMI, HI), region, Rule of Law, and Government Effectiveness, respectively. Governance dummies were constructed from Worldwide Governance Indicators (1996–2018), categorizing countries in each period into four states based on average level and change: Strong & Getting Stronger; Strong & Getting Weaker; Weak & Getting Stronger; Weak & Getting Weaker. Attribution method: Using fitted values from regressions with dummy sets, the authors computed the proportion of ULE attributed to population growth versus GDP per capita growth for each category (region, income group, governance state) as the mean fitted contribution of each driver divided by the sum of both drivers’ fitted contributions within the category. This yields percentage attributions for population and GDP per capita to ULE across contexts and periods. Software: Analyses conducted in R (v4.0.3); packages included plyr, tidyverse, ggpubr, hrbrthemes, gridExtra, ggrepel, psych, sandwich, stargazer, and spatial packages raster, rgdal, sf for GHSL processing.

- Average growth rates (2000–2014, million-plus cities): ULE grew at 1.08% annually on average, versus 1.58% for population and 4.21% for GDP per capita.

- Regional patterns: Population growth exceeded ULE in Africa, Middle East, India, Central & South America, and North America; ULE exceeded population growth in China, East & Southeast Asia, and Europe. Cities in Europe and North America had the lowest ULE and population growth rates. GDP per capita growth exceeded ULE most notably in China (6–15%), followed by India (2–7%) and E&SE Asia; many African cities had higher ULE than GDP per capita growth.

- Regression results (Table 1): Population growth is the dominant driver of ULE in both periods. Pre-2000 (Model I): a one-unit increase in population growth rate is associated with a 0.161 increase in log ULE (% annual), and GDP per capita with 0.073; Post-2000: population 0.230, GDP per capita 0.124. Effect sizes for both drivers increased post-2000. Results are robust across models controlling for region, income, and governance; interactions are insignificant. R² increased from ~0.21 (pre-2000) to ~0.28 (post-2000) in Model I and up to ~0.31 with controls.

- Differences by income and region: Pre-2000, high-income countries’ ULE rates differed significantly from other groups after controls; post-2000, HI and UMI were not significantly different. Regionally, pre-2000 ULE rates (vs North America) were highest in India, followed by China and Africa; post-2000, Africa had the highest, with convergence in ULE rates across regions over time.

- Attribution by income (inverted U-shape): GDP per capita’s contribution to ULE is lowest in low-income countries, increases substantially in LI/LMI/UMI from pre-2000 to post-2000, then declines in HI countries. In North America, GDP’s contribution fell from 38% to 26%, while population’s rose from 63% to 74% (rounding).

- Attribution by region: GDP’s contribution to ULE increased from pre- to post-2000 in China (largest increase), India, Central & South America, and Africa.

- Urbanization vs income vs urban land: National income correlates strongly with urbanization level, but there is little correlation between national income and the share of urban land area. Some low-income African countries exhibit urban land shares comparable to high-income countries without corresponding income gains, suggesting weak agglomeration benefits and inefficient land use.

- Governance effects: Stronger governance conditions enable economic growth to account for a larger share of ULE. From pre- to post-2000, in countries with improving governance (Weak & Getting Stronger and Strong & Getting Stronger), GDP per capita explains more of ULE. Under Rule of Law, in post-2000, over 70% of ULE is attributed to GDP per capita in the Weak & Getting Stronger category. Under Government Effectiveness, GDP’s contribution increased markedly in Strong & Getting Stronger countries. Overall, effective governance is necessary for GDP growth to substantially influence ULE.

- Overall takeaway: Population growth consistently exerts a larger effect on ULE across contexts and time; GDP per capita becomes relatively more important post-2000 in select contexts (e.g., China and some Middle Eastern countries with stronger governance).

Findings indicate that population growth is the primary driver of ULE across regions and development stages, with GDP per capita’s role strengthening after 2000 in many developing and middle-income contexts. This has significant implications for sustainability given projected population growth in low-income regions: rapid ULE without commensurate economic growth may exacerbate environmental impacts and undermine agglomeration economies. The observed inverted U-shape suggests that at earlier development stages, GDP per capita growth facilitates infrastructure and agglomeration, attracting migrants and contributing to ULE; in high-income contexts, population dynamics and amenity-driven migration become more salient. Governance quality mediates these dynamics: stronger rule of law and government effectiveness support market functioning, planned development, and infrastructure investment, enabling GDP growth to translate into ULE; weak governance limits economic development’s influence, leaving ULE primarily population-driven and often sprawling and unplanned. The authors discuss supply-demand dynamics of land markets, the role of policy (zoning, planning, infrastructure), and potential disruptions (e.g., pandemics) that can alter migration, economic activity, and ULE trajectories. Methodologically, the study underscores the value of city-level analysis to capture heterogeneity obscured by national aggregation and highlights the need to consider population, economy, and governance jointly when managing ULE.

The study provides global, city-level evidence over 1970–2014 that urban population growth is the dominant driver of urban land expansion, while the influence of GDP per capita on ULE has increased since 2000, particularly in countries with stronger governance. Governance quality is a necessary condition for economic growth to significantly affect ULE. Policy implications include targeting ULE indirectly through instruments that influence local population and economic growth and aligning economic development with integrated, sustainable spatial planning. With 2.5 billion additional urban residents expected by 2050, proactive policies are essential to protect critical land ecosystems and guide urban form. Future research should examine how shocks (e.g., pandemics, climate-related disasters) reshape ULE, expand city-level datasets in underrepresented regions, and further integrate governance metrics into models of urban expansion.

- City-level GDP data were unavailable pre-2000; GDP growth was measured at national or subnational levels (province/state), which may introduce mismatch with city-scale dynamics.

- Post-2000 economic and population data rely in part on proprietary sources (Oxford Economics), potentially limiting transparency and reproducibility.

- Sample focuses on large cities (mostly >1 million), which may limit generalizability to smaller urban areas.

- Negative growth rates for population and GDP per capita were capped at zero, and only positive ULE rates were analyzed, which may bias interpretations toward growth contexts.

- Model explanatory power is modest (R² ~0.2–0.3); many local drivers (policies, geography, market conditions) are not explicitly modeled.

- Governance indicators are national-level composites and may not fully capture city-level institutional variation or changes within the study windows.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.