Business

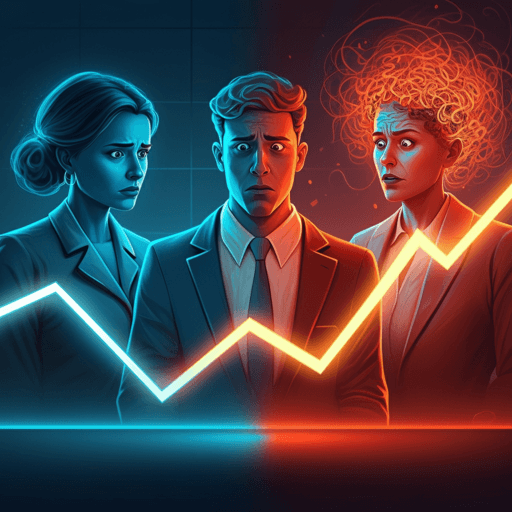

Trying to think: An experimental study of the impact of cognitive load on financial risk taking by groups

E. Lahav, R. Manos, et al.

This research was conducted by E. Lahav, R. Manos, G. Kashy-Rosenbaum, and N. Sitbon. Using a game-like investment experiment with individuals, groups, and gender-heterogeneous groups, the study finds that cognitive load raises risk-taking for both individuals and groups; joining a group and prior losses also increase risk appetite, though the effect of past losses weakens under cognitive load — with clear implications for corporate decision-making.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.