Biology

The role of extracellular polymeric substances of fungal biofilms in mineral attachment and weathering

R. Breitenbach, R. Gerrits, et al.

Explore the fascinating interplay between extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and mineral weathering through the lens of genetically modified biofilms of the rock-inhabiting fungus Knufia petricola. This research, conducted by Romy Breitenbach, Ruben Gerrits, Polina Dementyeva, Nicole Knabe, Julia Schumacher, Ines Feldmann, Jörg Radnik, Masahiro Ryo, and Anna A. Gorbushina, unveils how melanin production influences EPS generation and mineral dissolution rates.

~3 min • Beginner • English

Introduction

Fungi are major agents of mineral weathering and biofilm formation across terrestrial environments, influencing biogeochemical cycles. Rock-inhabiting black fungi, ubiquitous on sun- and air-exposed mineral surfaces, endure environmental stresses and contribute to weathering and soil formation. These organisms produce extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) and DHN melanin, both forming protective outer layers that mediate adhesion, desiccation tolerance, and interactions with metals. While EPS and melanin protective roles are known, the specific contribution of EPS to mineral weathering remains ambiguous, with reports of both enhancement and inhibition. This study aims to mechanistically link EPS quantity/composition and melanin biosynthesis to fungal attachment and silicate weathering, using Knufia petricola A95 wild type and pigment biosynthesis mutants to test how EPS features and melanin (or its intermediates) affect attachment to olivine and its dissolution rate.

Literature Review

Prior work establishes that fungal biofilms initiate colonization of mineral surfaces and contribute to rock weathering and soil formation. Black fungi produce DHN melanin via a pathway involving T4HN, scytalone, T3HN, vermelone, and DHN, catalyzed by conserved reductases (including scytalone reductase, SDH) and a polyketide synthase (PKS); knocking out late enzymes accumulates colored intermediates, whereas PKS deletion abolishes precursors. EPS matrices (proteins, lipids, polysaccharides, DNA) mediate adhesion, water retention, and protection against antimicrobials and metals; however, EPS can both enhance silicate dissolution and impede other metabolite actions. Previous analysis of K. petricola EPS showed corrosive extracellular polysaccharides and specific glycosidic linkages. The ambiguity of EPS roles and the interplay with melanin prompted targeted genetic approaches to dissect mechanisms of attachment-driven weathering and metal interactions (e.g., Fe chelation/adsorption).

Methodology

Model organism: Knufia petricola A95 wild type (WT) and pigment mutants: Δpks1 (no melanin intermediates), Δsdh1 (no melanin but accumulates scytalone and other intermediates), Δphd1 (no carotenoids, accumulates phytoene), and Δpks1/Δphd1 (no melanin, no colored carotenoids).

Biofilm cultivation: Subaerial biofilms grown on cellulose acetate filters atop malt extract agar at 25 °C for 7 days. Additional growth for XPS on Czapek-Dox with cellophane overlay; biofilms freeze-dried.

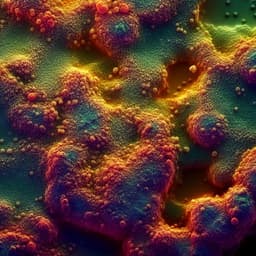

Microscopy: Biofilm and cell wall structures imaged by cryo-SEM, SEM, and TEM (glutaraldehyde fixation, OsO4 post-fixation, ethanol dehydration, Spurr embedding; ultrathin sections stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate). CLSM used for lectin binding.

EPS extraction and analyses: EPS extracted from pooled biofilms via formaldehyde stabilization and NaOH extraction; precipitated with ethanol. Integrity of cells verified by light microscopy. EPS mass quantified gravimetrically. Monosaccharide composition and glycosidic linkage analysis performed via GC-MS of (permethylated) alditol acetates. FTIR (4000–800 cm−1) used to identify functional groups and polysaccharide fingerprints. XPS on freeze-dried biofilms to determine near-surface elemental ratios (C, O, N).

Lectin screening: Fluorescent lectin barcoding on WT and Δpks1/Δphd1, followed by detailed binding with selected lectins (HHA, GNA) on WT, Δpks1, Δpks1/Δphd1.

Olivine dissolution experiments: Batch reactors (500 mL polycarbonate flasks) with 4.00±0.001 g forsteritic olivine (63–125 μm, cleaned; SSA measured by BET with krypton), 400 mL CNPS minimal medium buffered at pH 6.00. Inoculation to 5×10^7 CFU L−1; incubation 69 days at 25 °C, light 90 μmol photons m−2 s−1, shaking 150 rpm (solids not kept in suspension during growth; suspension achieved during sampling). Triplicate biotic runs per strain and abiotic control. Periodic sampling (5 mL) for pH and dissolved elements; samples filtered (0.22 μm), acidified for ICP-OES (Mg, Si, Fe) with quantified analytical uncertainties and detection limits. Final biomass estimated by dry weight difference (biotic minus abiotic). Grade of attachment quantified by counting colonized grains under dissecting microscope at day 69. SEM prepared via critical point drying and sputter coating.

Dissolution rate calculation: Rates r(t) computed from Mg concentration increments between time points, reactor olivine mass accounting for sampling, specific surface area (initial BET), and stoichiometric Mg coefficient (1.8557). Final rates based on Mg difference between day 6 and 55 due to analytical limitations after day 55.

Thermodynamic/kinetic context: Calculated ΔG of dissolution and assessed potential inhibition by approach to equilibrium (TST) and compared to unconventional stepwave model thresholds.

Statistics: One-way ANOVA with Tukey-HSD for mean differences; Pearson correlation among EPS amount, α-glucan-related linkages, attachment grade, and day-55 dissolution rate (n=5). Confidence intervals reported; no multiple-testing correction due to small sample size.

Key Findings

- Biofilm morphology and cell wall: WT and Δphd1 formed thicker biofilms; melanin-deficient Δpks1 and Δpks1/Δphd1 formed flatter biofilms; Δsdh1 intermediate thickness. Melanin layer detected in WT and Δphd1 cell walls; absent in Δpks1 and Δpks1/Δphd1; Δsdh1 showed interrupted pigmentation. EPS sheath visible around all strains, more distinct in melanin-lacking mutants.

- EPS quantity: WT 102.9 ± 5.0 mg g−1; Δphd1 107 ± 23 mg g−1 (ns vs WT); Δpks1 189 ± 45 mg g−1 (significantly higher, p < 0.05, n=3); Δsdh1 136 ± 33 mg g−1 (ns); Δpks1/Δphd1 188 ± 75 mg g−1 (ns).

- Lectin binding: 12 lectins bound WT EPS; 26 bound Δpks1/Δphd1, with 16 exclusively binding the double mutant; NPA and PMA bound only WT. HHA and GNA (α-mannose specificity) showed stronger binding in melanin-deficient mutants; GNA revealed double-ring patterns distinguishing cell wall vs EPS in WT.

- XPS/FTIR: Similar O/C and N/C across strains except Δsdh1 with elevated N/C indicating higher protein content. FTIR bands 3305–3262 cm−1 stronger for Δsdh1 (amide/amine/O–H), 1661–1552 cm−1 (amide) weaker in WT. Carbohydrate region (1200–1000 cm−1): WT and Δphd1 maxima at ~1021–1029 cm−1 (glucose-dominant); melanin mutants shifted to 1075 (Δpks1), 1080 (Δpks1/Δphd1), 1082 cm−1 (Δsdh1), indicating increased mannose/galactose.

- Monosaccharide composition (%): WT: Man 21 ± 11, Glc 66.3 ± 5.4, Gal 12.3 ± 5.8. Δphd1: Man 25 ± 14, Glc 60 ± 15, Gal 14.72 ± 0.74 (similar to WT). Δpks1: Man 31 ± 12, Glc 41.9 ± 5.7, Gal 26.9 ± 6.5. Δpks1/Δphd1: Man 32, Glc 41, Gal 27. Δsdh1: Man 36.8 ± 2.6, Glc 38.9 ± 8.2, Gal 24.3 ± 5.6.

- Glycosidic linkages: All WT linkages present in mutants. Δphd1 similar to WT overall. Melanin-free Δpks1 and Δpks1/Δphd1 had decreased (1→4)-Glcp and (1→6)-Glcp (though their ~2:1 ratio preserved) and increased terminal (1→)-Glcp/Manp/Galf, and (1→2)-Manp, (1→3)-Glcp, (1→6)-Galf. Δsdh1 intermediate between WT and Δpks1. Correlation: attachment grade positively correlated with α-glucan-related ((1→4)-Glcp and (1→6)-Glcp) linkage fraction (r = 0.94, 95% CI [0.35, 1.00], p = 0.017).

- pH: Remained ~6.0; final pH slightly but significantly lower for Δpks1 (5.90 ± 0.02) and Δpks1/Δphd1 (5.90 ± 0.02) vs WT (5.99 ± 0.03), Δphd1 (5.97 ± 0.04), Δsdh1 (6.02 ± 0.02), abiotic (6.02 ± 0.04) (p < 0.01, n=3).

- Dissolved concentrations: Mg and Si release generally stoichiometric (Mg/Si ~ 1.856). Lowest in abiotic; then Δpks1 and Δpks1/Δphd1; higher in WT and Δphd1; highest in Δsdh1 (all differences significant, p < 0.01, n=3). Fe concentrations and Fe/Si ratios were significantly higher in Δsdh1, Δpks1, Δpks1/Δphd1 vs abiotic, WT, Δphd1, indicating greater Fe retention in solution by melanin-deficient and Δsdh1 strains.

- Dissolution rates at day 55 (×10^−16 mol cm−2 s−1): Abiotic 9.7 ± 4.1; Δpks1 17.6 ± 6.5; Δpks1/Δphd1 18.8 ± 6.9; WT 38 ± 13; Δphd1 34 ± 12; Δsdh1 59 ± 19. All biotic > abiotic (p < 0.01). WT and Δphd1 > Δpks1 and Δpks1/Δphd1 (p < 0.01). Δsdh1 highest (p < 0.01).

- Attachment (day 69): WT 28.7 ± 8.4%; Δphd1 47 ± 12%; Δsdh1 19.3 ± 3.4%; Δpks1 6.8 ± 3.2%; Δpks1/Δphd1 5.4 ± 2.6%. WT, Δphd1, Δsdh1 attached more than Δpks1 and Δpks1/Δphd1 (p < 0.01). SEM confirmed attachment patterns and EPS presence on cells.

- Time dependence: Abiotic dissolution inhibited relative to literature rates; attachment effect on Mg release prominent up to day 55. Difference in Mg between WT and Δsdh1 increased throughout, consistent with sustained chelation effects in Δsdh1.

Interpretation: Melanin-producing strains with higher pullulan-related α-glucan linkages attached better and exhibited higher olivine dissolution. Δsdh1 likely released phenolic melanin intermediates acting like Fe-chelating agents, further enhancing dissolution.

Discussion

The study links EPS composition and melanin biosynthesis to fungal attachment and olivine weathering. Melanin-deficient mutants produced more EPS, suggesting compensatory protection in the absence of melanin; however, despite higher EPS amounts, melanin-lacking strains showed reduced attachment and lower dissolution rates compared with melanized strains, implicating EPS composition—particularly α-glucan (pullulan)-related linkages—in adhesion and weathering efficiency. The strong positive correlation between α-glucan linkages and attachment supports pullulan-like polymers’ role in surface adhesion. Attachment likely enhances weathering by mitigating Fe(III) precipitation at the mineral surface via proximity-enabled Fe uptake, adsorption onto EPS/melanin, and enhanced siderophore efficacy, thereby preventing abiotic inhibition. Local pH changes at the biofilm–mineral interface appeared limited under these conditions. The Δsdh1 mutant diverged from this pattern: despite only moderate attachment, it exhibited the highest dissolution rate and elevated Mg, Si, and Fe in solution, consistent with release of phenolic melanin intermediates (e.g., flaviolin) that chelate Fe (and other metals), acting similarly to siderophores and sustaining inhibition avoidance of Fe-oxide passivation. Thus, both biomechanical (attachment-mediated) and biochemical (Fe chelation/adsorption) mechanisms contribute to fungal enhancement of olivine dissolution, with EPS composition and melanin pathway intermediates modulating these processes.

Conclusion

By integrating genetic manipulation of pigment pathways with multi-modal EPS characterization and olivine dissolution experiments, the study demonstrates that EPS composition—particularly pullulan-related α-glucan linkages—promotes fungal attachment and enhances mineral weathering. Melanized strains with more pullulan-like linkages attached more strongly to olivine and dissolved it faster. The Δsdh1 mutant released phenolic melanin intermediates that likely chelate Fe, further boosting dissolution beyond attachment effects. Overall, extracellular matrix composition and substrate attachment are key, intrinsic properties enabling black fungi to influence silicate weathering; careful quantitative and compositional analyses of biofilm microenvironments are essential to understand these interactions. Future work should dissect the roles of non-polysaccharide EPS components (e.g., proteins, DNA) and directly quantify in situ interfacial chemistry (e.g., Fe speciation, interfacial pH/redox) to resolve their contributions to attachment and metal handling.

Limitations

- EPS extraction may incompletely represent tightly bound matrix; however, cell integrity was checked. XPS probed only shallow surface layers and may overestimate carbon due to adventitious contamination; comparisons focused on relative differences.

- BET surface area measured only for fresh olivine; SSA of biotically reacted samples could not be measured due to cell coverage; rates used initial SSA.

- Dissolution rates after day 55 could not be robustly calculated because Mg concentration differences between day 55–69 were within ICP-OES analytical uncertainty; final rates reported for day 6–55.

- Chemistry of submicron mineral precipitates in EPS could not be resolved by EDS.

- Batch conditions may have led to nutrient limitation/metabolite accumulation and time-varying attachment effects.

- Small sample size for some analyses (e.g., monosaccharides for Δpks1/Δphd1 had one replicate); no multiple-testing correction applied.

- Interfacial pH and redox were not directly measured; mechanisms inferred from solution chemistry and microscopy.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.