Medicine and Health

Targeting USP2 regulation of VPRBP-mediated degradation of p53 and PD-L1 for cancer therapy

J. Yi, O. Tavana, et al.

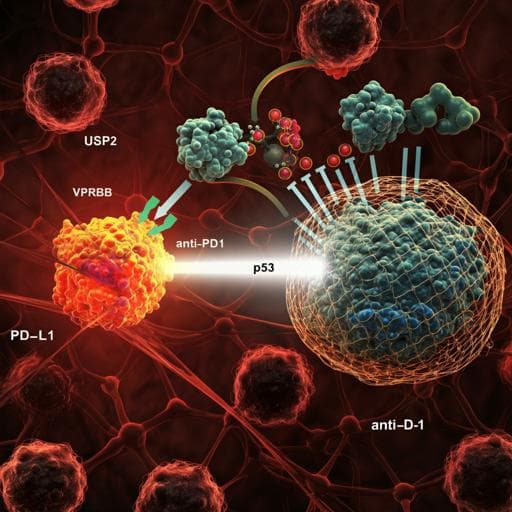

The study addresses the need for alternative strategies to therapeutically reactivate p53 tumor suppressor function in cancers that retain wild-type TP53, given the dose-limiting toxicities of Mdm2 inhibitors in clinical trials. Mdm2 and p53 form a negative feedback loop critical for maintaining normal tissue homeostasis; disrupting this loop with Mdm2 inhibitors unleashes p53 activity in normal tissues and causes severe toxicity. Prior work suggests that enhancing p53 function without compromising Mdm2-mediated regulation may avoid toxicity (e.g., Super-p53 mice with intact Mdm2). VPRBP (DCAF1) has been identified as a corepressor and E3 ligase adaptor that represses p53 transcription and promotes its ubiquitin-mediated degradation independently of Mdm2, and is overexpressed in several cancers. The authors hypothesize that targeting the USP2-VPRBP pathway—specifically by inhibiting USP2, a deubiquitinase that stabilizes VPRBP—can activate p53 in tumors while preserving the p53-Mdm2 feedback in normal tissues, and that this axis also regulates PD-L1 with implications for combining with PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade.

- Clinical Mdm2 inhibitors effectively reactivate p53 but have significant toxicities (myelosuppression, GI symptoms, weight loss, fatigue, cardiovascular toxicity, and treatment-related death), reflecting disruption of the p53-Mdm2 negative feedback loop.

- Genetic evidence: Mdm2-null mice are embryonically lethal unless p53 is also inactivated; compromising Mdm2 regulation of p53 (Mdm2 P2 promoter mutants) causes catastrophic myeloablation upon DNA damage. By contrast, Super-p53 mice with intact Mdm2 regulation show enhanced p53 responses without toxicity.

- p53 function is dynamically regulated by post-translational modifications; acidic domain-containing cofactors act as readers of unacetylated p53. VPRBP is an acidic domain-containing corepressor, binds p53 C-terminus, represses p53-mediated transcription, and participates in p53 ubiquitination and degradation in vivo.

- PD-L1 expression in tumors is induced by IFNγ via IRF1; PD-L1 levels correlate positively with response to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade.

- USP2-knockout mice develop normally with mild phenotypes, suggesting limited essential roles in normal tissue homeostasis. These observations motivate exploring USP2/VPRBP as a therapeutic target to activate p53 while mitigating toxicity and potentially synergizing with immune checkpoint therapy.

- Cell lines: Human cancer lines (U2OS, H1299, H460, A375, CAL33, A549, SKBR3, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-435, HUCCT1, HEK293T) and murine lines (EMT6, EMT6 p53-null CRISPR, 4T1, B16F10, RM-1). Cells cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS, penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C, 5% CO2. Cell lines were not authenticated.

- Gene perturbations:

- siRNA knockdown: VPRBP, p53, USP2, DDB1, CUL4A/B using commercial siRNA pools; controls included non-targeting siRNAs.

- shRNA: Four independent shRNAs against VPRBP for stable knockdown in EMT6 (lentiviral transduction).

- CRISPR/Cas9 knockouts: Generated IRF1-null H1299; USP2-knockout H1299 via double nickase plasmids; p53-null EMT6 using inducible Cas9 and gRNA. Knockouts validated by immunoblot and sequencing.

- Protein interaction and mechanistic assays:

- Co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) for interactions among VPRBP, IRF1, PD-L1, USP2 at exogenous and endogenous levels.

- GST pull-down assays with purified proteins to test direct interactions: VPRBP with IRF1; VPRBP with PD-L1; VPRBP with USP2; domain mapping for PD-L1 (ICD aa231–290) and VPRBP N-terminus required for binding.

- Ubiquitination assays under denaturing conditions to assess VPRBP-induced PD-L1 ubiquitination and USP2 effects on VPRBP ubiquitination.

- Cycloheximide (CHX) chase assays to measure protein half-lives of PD-L1 and VPRBP in control vs knockdown/KO backgrounds.

- Luciferase reporter assays: PD-L1 promoter (-456 to +151) containing two IRF1 sites to assess IRF1 activation and VPRBP repression; tested with WT and mutant VPRBP (ΔAD/AAD lacking IRF1-binding; ΔE3 defective for CUL4-DDB1 interaction).

- qRT-PCR for mRNA levels (PD-L1, USP2, VPRBP) and p53 targets; Western blots for PD-L1, VPRBP, USP2, p53, p21, PUMA, MDM2, DDB1, CUL4A/B, IRF1.

- Small molecule treatments:

- USP2 inhibitors: ML364 (typically 20 µM, 72 h in vitro; 30 mg/kg daily IP for 15 days in vivo), LCAHA (20 µM, 72 h).

- Mdm2 inhibitor: RG7388 (idasanutlin) at 1–10 µM for rescue of Mdm2-mediated p53 degradation in vitro.

- CUL4 E3 inhibitor: MLN4924 to assess dependence of VPRBP-mediated PD-L1 degradation on CRL4 activity; lysosomal inhibitor BafA1 as control.

- In vivo studies:

- Xenografts in immunodeficient nude mice: EMT6 (WT or p53-null) with/without VPRBP knockdown; tumor dissection and weight measurement ~2 weeks post-inoculation.

- Syngeneic models in immunocompetent mice: EMT6-Luc in Balb/c females; RM-1 in C57BL/6 males; treatment arms included vehicle, ML364, anti-PD-1 mAb, and combination. Anti-PD-1 dosing: 200 µg/mouse IP, 4 injections over ~10 days. Tumor volumes monitored; IVIS imaging for EMT6-Luc.

- Immune profiling: Flow cytometry of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs): CD4+, CD8+, granzyme B+; CD4/CD8 depletion assays using depleting antibodies to dissect effector populations.

- Toxicity assessment: Balb/c mice treated with ML364 (30 mg/kg IP daily for 10 days); complete blood counts (WBC, lymphocytes), histology (H&E) of bone marrow, spleen, and major organs; body weight monitoring.

- Statistics: Unpaired two-tailed t-tests for in vitro assays; log-rank tests for survival analyses; data presented as mean ± SD/SEM with biological replicates as indicated.

- VPRBP suppresses p53 activity and regulates PD-L1 independently of p53:

- VPRBP knockdown elevated p53 target genes (p21, TIGAR, PUMA, MDM2) in p53-WT U2OS but not p53-null cells.

- VPRBP depletion increased PD-L1 mRNA and protein across multiple cell lines regardless of p53 status; PD-L1 upregulation persisted with concurrent p53 knockdown and in p53-null cells.

- Mechanisms of PD-L1 regulation by VPRBP:

- VPRBP directly binds IRF1 and represses IRF1-driven PD-L1 promoter activity; VPRBP co-expression reduced IRF1-induced endogenous PD-L1 without altering IRF1 levels.

- IRF1 knockout abrogated IFNγ-induced PD-L1 expression; VPRBP knockdown failed to elevate PD-L1 in IRF1-null cells, indicating dependence on IRF1.

- VPRBP also binds PD-L1 (via PD-L1 C-terminal intracellular domain, aa231–290) and promotes its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation through CRL4VPRBP E3 ligase; DDB1 or CUL4A/B knockdown upregulated PD-L1; MLN4924 blocked VPRBP-mediated PD-L1 degradation. VPRBP mutants deficient in PD-L1 binding or E3 association failed to induce degradation.

- VPRBP inhibition suppresses tumor growth in vivo in a p53-dependent manner:

- shVPRBP reduced growth of EMT6 tumors in nude mice; effect largely lost in p53-null EMT6 xenografts.

- In immunocompetent Balb/c mice, shVPRBP alone modestly reduced EMT6 tumor growth in a subset (2/11), but combination with anti-PD-1 suppressed growth in all mice (11/11) and improved survival (log-rank p<0.0001), with increased CD8+/granzyme B+ TILs.

- USP2 is a deubiquitinase that stabilizes VPRBP:

- USP2 physically interacts with VPRBP (co-IP, direct GST pull-down). Wild-type USP2, but not catalytic mutant C276A, stabilized VPRBP and reduced its ubiquitination.

- USP2 knockdown or CRISPR knockout reduced VPRBP protein (not mRNA) and shortened its half-life.

- USP2 inhibition activates p53 while preserving Mdm2 regulation and elevating PD-L1:

- USP2 inhibitors (ML364, LCAHA) destabilized VPRBP, increased PD-L1, and activated p53 targets (p21, PUMA, MDM2) in p53-WT lines; PD-L1 induction occurred irrespective of p53 status.

- ML364 did not block Mdm2-mediated p53 degradation, unlike RG7388; Usp2-null cells retained intact p53-Mdm2 feedback (normal Mdm2 half-life; exogenous Mdm2 degraded p53; p53 induced Mdm2).

- Therapeutic efficacy and safety in vivo:

- ML364 (30 mg/kg daily x15) or anti-PD-1 alone conferred long-term survival in subsets of EMT6-bearing Balb/c mice (ML364 ~3/8; anti-PD-1 ~5/8), whereas combination achieved complete responses with long-term survival in all mice (9/9), with marked tumor regression by bioluminescence.

- In p53-null EMT6 tumors, combination therapy was much less potent (long-term survival 3/6), indicating dependence on tumor cell-autonomous p53 activity.

- Similar synergy reproduced in RM-1 tumors without apparent toxicity.

- CD8+ T cells were essential for combination efficacy (CD8 depletion abrogated effect; CD4 depletion had little effect).

- Toxicity: ML364 treatment showed no significant hematologic toxicity (WBC, lymphocytes not different from vehicle), no histologic damage to bone marrow/spleen/major organs, and stable body weight.

The study demonstrates that targeting the USP2-VPRBP axis activates p53 tumor suppressor function while simultaneously modulating PD-L1 through IRF1 repression and ubiquitin-mediated degradation. By destabilizing VPRBP via USP2 inhibition, p53 transcriptional activity is enhanced in tumor cells; critically, this occurs without disrupting the essential p53-Mdm2 negative feedback loop, likely avoiding the severe toxicities observed with Mdm2 inhibitors. The upregulation of PD-L1 resulting from VPRBP/USP2 inhibition presents a paradox for anti-tumor immunity but also creates a vulnerability: elevated PD-L1 sensitizes tumors to PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade. Consequently, combining a USP2 inhibitor with anti-PD-1 therapy elicits robust anti-tumor responses, increases cytotoxic CD8+ TILs, and achieves complete tumor regression and durable survival in p53-WT tumor models. The results underscore a therapeutically exploitable strategy to reactivate p53 in a manner compatible with normal tissue homeostasis, and they provide mechanistic insight linking deubiquitination, transcriptional repression, and immune checkpoint regulation via VPRBP.

This work identifies USP2 as a key deubiquitinase that stabilizes VPRBP, a dual regulator of p53 and PD-L1. Pharmacologic or genetic inactivation of USP2 destabilizes VPRBP, thereby activating p53 and increasing PD-L1 expression through IRF1-dependent transcription and relief of CRL4VPRBP-mediated PD-L1 degradation. Unlike Mdm2 inhibition, USP2 inhibition preserves the p53-Mdm2 feedback loop and shows no obvious toxicity in vivo. Therapeutically, USP2 inhibition alone partially suppresses tumors, but in combination with PD-1/PD-L1 blockade, it drives complete regression and long-term survival in p53-WT murine tumor models, with efficacy dependent on CD8+ T cells and tumor cell-autonomous p53. Future research should define the precise mechanisms underlying the favorable safety profile of USP2 inhibition, investigate potential p53-independent roles of USP2 in tumorigenesis and toxicity, and evaluate this combination strategy in clinical trials, including in tumors refractory to immunotherapy.

- The precise mechanism by which USP2 inhibition avoids toxicity compared to Mdm2 inhibition remains unresolved and requires further study.

- Potential p53-independent functions of USP2 that may influence efficacy or toxicity were not fully delineated.

- Efficacy was demonstrated in preclinical cell line and murine syngeneic/xenograft models; clinical translation remains to be tested.

- Cell lines used were not authenticated, which may impact generalizability of some in vitro findings.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.