Psychology

Reduced adaptation of glutamatergic stress response is associated with pessimistic expectations in depression

J. A. Cooper, M. R. Nuutinen, et al.

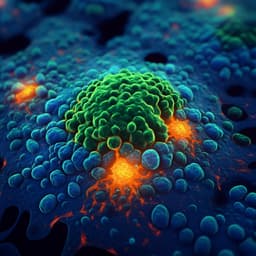

This study, led by a team of researchers including Jessica A. Cooper and Victoria M. Lawlor, reveals fascinating insights into how stress affects glutamate in the human brain, specifically in the medial prefrontal cortex. While healthy individuals show an adaptive response to stress, this response is disrupted in those with major depressive disorder (MDD). Discover how this research uncovers the neurochemical nuances of stress and depression.

Playback language: English

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.