Engineering and Technology

Programmable adhesion and morphing of protein hydrogels for underwater robots

S. Huang, Y. Zhu, et al.

Discover the innovation in soft robotics driven by Sheng-Chen Huang, Ya-Jiao Zhu, Xiao-Ying Huang, Xiao-Xia Xia, and Zhi-Gang Qian. Their research reveals how dynamic underwater robots, constructed from designer protein materials, can seamlessly switch between adhesive and non-adhesive states, leveraging temperature changes for complex tasks in aquatic environments.

~3 min • Beginner • English

Introduction

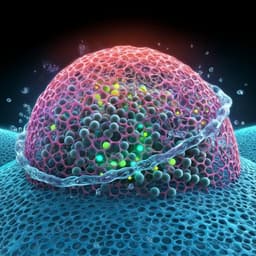

Underwater soft robots promise applications from medical tools and sensors to ocean exploration due to their ability to operate in fluid environments. A central challenge limiting performance is achieving controllable, strong adhesion to diverse surfaces underwater, where hydration layers impede interfacial interactions. Bioinspired approaches have yielded underwater adhesives, commonly via catechol (L-DOPA) chemistry, but these often lack dynamic responsiveness and suffer catechol over-oxidation. Complex coacervation of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes offers tunable, stimulus-responsive adhesion, yet reported systems typically show poor mechanics and limited controllable attachment/detachment across substrates, hindering complex robotic tasks like catching, locomotion, and morphing. This work develops a gel-type underwater adhesive using controllable complexation between positively charged, intrinsically disordered resilin-like proteins (RLPs) and Keggin-type polyoxometalates (silicotungstic acid, SiW). The resulting hydrogels rapidly switch between non-adhesive rigid and adhesive soft states within a mild temperature window. Incorporation of Fe3O4 nanoparticles provides photothermal and magnetic responsiveness, enabling remote control of adhesion, locomotion, and morphing for tasks such as multi-cargo capture/delivery and artificial blood vessel repair.

Literature Review

- Soft robotic materials include liquid crystal polymers, dielectric elastomers, and stimuli-responsive hydrogels, each with strengths but limited underwater adhesion control.

- Underwater adhesion is impeded by hydration layers; marine organisms use protein-based adhesives, inspiring synthetic systems.

- Catechol-based adhesives (mussel-inspired) are prevalent but often lack dynamic, reversible control and can lose adhesiveness via catechol over-oxidation.

- Complex coacervation of oppositely charged polyelectrolytes provides dynamically tunable adhesion, yet typical systems have inadequate mechanical robustness and limited controllable attachment/detachment across diverse substrates.

- Polyoxometalates (POMs), especially Keggin-type SiW, have rigid frameworks, defined topology, and high ionization in water, enabling strong multivalent electrostatics with cationic polymers/proteins. Prior works have explored POM–protein interactions and POM-assisted underwater adhesives, motivating their use to create robust, dynamic protein hydrogel adhesives with programmable mechanics and adhesion.

Methodology

Biosynthesis of R32 protein: A resilin-like protein (R32, 32 repeats of GGRPSDSYGAPGGGN containing tyrosine and arginine residues) was recombinantly produced in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) harboring pET19b-R32. Cells were cultivated in rich medium; R32 was purified from lysate via immobilized metal affinity chromatography, dialyzed, and lyophilized. Purity (>95%) was confirmed by SDS-PAGE; identity by MALDI-TOF MS. The full amino acid sequence is provided in Supplementary Note 1.

Hydrogel preparation (SiW-complexed R32): Lyophilized R32 was dissolved in water. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP, 15,000 U/mL stock) and H2O2 (3%) were added to yield final concentrations: protein 200 mg/mL, HRP 600 U/mL, H2O2 0.03%. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C (0–20 min) to introduce di-tyrosine crosslinks to desired degrees (0, 5%, 15%, 30%). The pre-crosslinked solution was dispensed (0.5 mL/min) through a 0.5 mm needle into a 20 mL aqueous SiW bath (50 mg/mL), with the needle 30 cm above the bath to form ~20 µL droplets that immediately complexed with SiW into coacervate droplets. Gentle stirring (30 s) fused droplets into aligned fibrils; continued stirring (~10 min) formed a bulk hydrogel around the stir bar. Hydrogel was blotted before characterization. Four formulations were made: R32-SiW, R32-5%-SiW, R32-15%-SiW, R32-30%-SiW.

Magnetic/photothermal hydrogel (M-R32-5%-SiW): Monodispersed Fe3O4 nanoparticles were dispersed in pre-crosslinked R32 (5% di-tyrosine) at 15.5 mg/mL and processed as above to form SiW-complexed hydrogel containing ~6 wt% Fe3O4. This endowed photothermal heating under IR illumination and magnetic responsiveness.

Characterization: Water content determined by mass loss after lyophilization. Stability/degradation assessed by soaking gels in deionized water at 10–50 °C, monitoring weight over time (up to 240 h). Thermogravimetric analysis (25–900 °C, N2, 10 °C/min) quantified organic/inorganic fractions to estimate SiW:R32 molar ratios (decreasing from ~6.4:1 to 4.9:1 with higher di-tyrosine crosslinking). Di-tyrosine degree quantified by fluorescence after acid hydrolysis versus a di-tyrosine standard. FTIR and 183W NMR confirmed SiW incorporation and structural integrity within hydrogels. SEM imaged lyophilized gels, revealing aligned microfibrillar structures. Underwater oil (1,2-dichloroethane) contact angle on gel discs (20 mm dia, 5 mm thick) quantified surface wettability at different temperatures.

Mechanical testing: Rheology on AR-G2 (parallel plate 40 mm). Time sweeps at 37 °C (1% strain, 1 Hz) probed di-tyrosine gelation dynamics; temperature-switch response for R32-5%-SiW with time sweeps between 20 and 30 °C (1% strain, 1 Hz); frequency sweeps (0.3% strain) at 20 and 30 °C. Tensile tests on Instron 5944 (10 N load cell) used dumbbell gels (length 20 mm, width 6/2 mm, gauge 10 mm, thickness 2 mm) at 10 mm/min in a temperature-controlled water bath. Dynamic mechanical analysis (Q800) in submersion tensile mode (0.1% strain, 1 Hz, preload 0.1 N) recorded E′ and tan δ from 0 to 80 °C at 3 °C/min. Self-healing was evaluated by cutting dumbbell gels (35 mm overall; gauge 15 mm; thickness 2 mm), rejoining in molds, healing at set temperatures/times, and tensile testing at 25 °C.

Underwater adhesion (probe tack): Disc gels (10 mm dia, 1 mm thick) were tested in a water bath on Instron 5944 (100 N load cell) with temperature control. Sample adhered to target substrate fixed at bath bottom; a probe (stainless steel, PP, glass, paper, rubber, bone, heart, muscle, kidney, liver) applied 0.5 N preload for 30 s (~6 kPa). Detachment at 50 mm/min provided adhesion force curves and strengths. Adhesion onset temperature Ti determined at 0.5 °C intervals.

Photothermal tests: Disc gels (6 mm dia, 1 mm thick) submerged 5 cm below water surface (bath at 20 °C). A 600 W IR lamp placed 5–9 cm above hydrogel; temperature monitored by thermal camera. For reversible IR on/off cycles, local gel temperature, Young’s modulus, and adhesion were tracked.

Magnetic actuation and demonstrations: A cylindrical NdFeB magnet (4 cm dia, 8 cm height) provided static fields; position/orientation changes modulated direction/strength for elongation and navigation. IR lamp (600 W) within 20 cm of samples provided heating. Chameleon tongue inspired robot: a hydrogel tongue anchored to object A captured object B in water by IR heating above Ts and magnetic field-driven elongation, followed by cooling to lock shape and strengthen adhesion. Multi-cargo transport used a three-arm robot pre-adhered to a stainless steel disc anchor. Blood vessel repair used an S-shaped PMMA tube (ID 20 mm, wall 2 mm) with a 25 mm incision, filled with 37 °C pig blood; robot (10×10×5 mm) navigated and sealed under IR/magnet.

Statistics: Error bars, replicate numbers, and independent experiments reported per figure; source data provided.

Key Findings

- SiW-complexed R32 hydrogels exhibit temperature-dependent mechanics with sharp thermo-softening near room temperature. Softening temperatures (Ts) ranged ~20.4–26.7 °C, increasing with higher di-tyrosine crosslinking.

- Tensile tests showed two distinct states: below Ts, gels are rigid (higher Young’s modulus, lower strain at break); above Ts, gels are soft (lower modulus, higher strain). The modulus change is reversible across cycles.

- Underwater adhesion: R32-5%-SiW adhered to diverse substrates (hydrophilic, hydrophobic, and tissues) at 25 °C, with probe-tack strengths of ~30–40 kPa.

- Adhesion versus temperature showed a rise to a maximum then decline, reflecting adhesion–cohesion trade-offs. Adhesion onset temperatures (Ti) increased with di-tyrosine crosslinking: R32-SiW and R32-5%-SiW Ti ≈ −23.7 °C (near Ts), while R32-15%-SiW and R32-30%-SiW had Ti ≈ 43.5 °C and 52.7 °C, higher than their Ts, indicating an intermediate soft-but-non-adhesive state.

- Warm attaching then cooling dramatically enhanced underwater adhesion: after attaching above Ti and cooling to 4 °C, all hydrogels showed up to an order-of-magnitude higher adhesion; higher attaching temperatures and lower cooling temperatures yielded stronger adhesion. With ~3.14 cm² adhesion area, R32-30%-SiW could hang 15 kg underwater at 20 °C after warm attachment at 70 °C.

- Mechanistic basis for switchable adhesion: heating increases chain mobility and hydrophobicity (underwater oil contact angle ~43° at 30 °C vs relatively hydrophilic at 20 °C), facilitating intimate contact and adhesion; cooling reduces mobility and increases cohesion to lock the interface.

- Photothermal control: Incorporating ~6 wt% Fe3O4 (M-R32-5%-SiW) enabled IR-driven local heating in water by 12–33 °C within 3 min, surpassing Ts and Ti. Upon IR on/off, temperature cycled from ~20→45→~20 °C; Young’s modulus decreased from ~6.8 to 0.5 MPa and recovered; adhesion increased from 0 to ~50 kPa and returned, with minimal decay over cycles.

- Demonstrations: IR-triggered softening enabled a hydrogel bar (2×2×30 mm, 2.3 g) to bend under a 10 g load; IR-triggered adhesion allowed a small gel (0.2 g) to adhere to a probe and lift a 200 g submerged object when cooled. A chameleon-tongue inspired robot (0.5 g) captured a 1.6 g prey 15 mm away underwater by IR heating and magnetic elongation (capture after ~500 s; lift after additional ~220 s). Adhesion force decreased sharply when elongation exceeded ~4× due to inhomogeneous deformation and reduced cross-section.

- A three-arm robot captured and delivered three cargoes underwater within ~18 min via sequential IR/magnetic control. In an artificial blood vessel (PMMA, 20 mm ID) filled with warm pig blood, a robot navigated to a 25 mm incision, adhered, elongated to cover the wound under IR/magnetic control, and, after cooling, maintained a seal with no observable leakage for at least one week.

- Hydrogels showed good aqueous stability (10–25 °C for 240 h); at ≥37 °C extended soaking partially eroded gels, tunable by di-tyrosine crosslinking degree.

Discussion

The study addresses the key challenge of controllable, strong underwater adhesion for soft robots by engineering a protein hydrogel that couples dynamic electrostatic crosslinks (R32–SiW complexes) with tunable covalent cohesion (di-tyrosine). This architecture yields a sharp, reversible transition between rigid/non-adhesive and soft/adhesive states within a mild temperature window, enabling on-demand attachment/detachment and morphing in aqueous environments. The adhesion–cohesion balance explains the temperature-dependent adhesion peak: heating increases chain mobility and surface hydrophobicity to initiate interfacial bonding, while excessive softening diminishes cohesion and load-bearing capacity; cooling re-establishes cohesive network integrity to lock strong interfaces. Incorporation of Fe3O4 nanoparticles unlocks remote photothermal and magnetic control: IR heating modulates stiffness and initiates adhesion, while magnetic fields guide elongation and navigation; subsequent cooling fixes shape and strengthens bonds. These synergistic controls enable complex operations—precise capture and transport of multiple cargoes and sealing of a simulated blood vessel leak—demonstrating applicability to biomedical and underwater manipulation scenarios. The findings expand the design space for protein-based smart hydrogels, highlighting how programmable electrostatic interactions can deliver rapid, reversible mechanics and adhesion under water, a longstanding hurdle in soft robotics.

Conclusion

This work introduces a protein-based hydrogel adhesive formed by complexing a positively charged resilin-like protein (R32) with silicotungstic acid (SiW), achieving a sharp, reversible transition between adhesive soft and non-adhesive rigid states near room temperature. By integrating Fe3O4 nanoparticles, the material becomes remotely controllable via IR light and magnetic fields, enabling switchable adhesion, locomotion, and morphing underwater. The robots demonstrated multi-cargo capture/transport and effective sealing of an artificial blood vessel leak, underscoring potential for biomedical applications. Future research may focus on accelerating actuation and cooling (e.g., optimizing magnetic field strength, nanoparticle content, and thermal management), improving shape recovery and fatigue resistance, tailoring adhesion/cohesion balance for specific substrates and temperatures, and assessing long-term biocompatibility and in vivo performance for medical contexts.

Limitations

- Actuation speed: Shape morphing and cooling to lock strong adhesion required ~3–8 min, attributed to relatively weak magnetic fields and low Fe3O4 content; faster response may require optimized field strength, particle loading, or geometry.

- Shape recovery: After cooling, elongated robots did not fully recover original shapes; although thermal remolding is possible, inherent elastic recovery is limited.

- Thermal stability: At body and higher temperatures, prolonged soaking partially eroded gels, with extent dependent on di-tyrosine crosslinking degree.

- Load-bearing at high temperature: At elevated temperatures (e.g., 70 °C), cohesion decreases sufficiently to prevent lifting despite adhesion initiation.

- Environmental constraints: Photothermal heating efficacy depends on IR access and local water convection; magnetic control depends on field strength and accessibility.

- Biocompatibility/in vivo translation not evaluated here beyond ex vivo pig blood model.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.