Biology

Markerless tracking of an entire honey bee colony

K. Bozek, L. Hebert, et al.

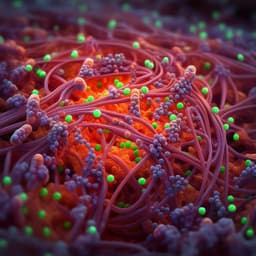

This study showcases a groundbreaking computational method utilizing convolutional neural networks to meticulously track honey bee colonies through high-resolution video. The research, conducted by Katarzyna Bozek, Laetitia Hebert, Yoann Portugal, Alexander S. Mikheyev, and Greg J. Stephens, reveals fascinating insights into bee behaviors, colony dynamics, and interactions, paving the way for advanced studies on collective insect behavior.

~3 min • Beginner • English

Introduction

The study addresses the challenge of quantifying collective behavior in dense, dynamic biological systems by achieving markerless, single-organism resolution tracking of all visible members of a honey bee colony and mapping colony resources (e.g., brood). Honey bee colonies comprise hundreds to thousands of visually similar, rapidly moving individuals on uneven combs with frequent occlusions, making automated detection and tracking difficult, and traditional solutions often rely on physical tags that are labor-intensive, disruptive, and prone to occlusion errors. The purpose is to develop a CNN-based method that detects bees and brood, estimates orientations and within-cell states, and tracks individuals using learned visual features, enabling long-term sociometric monitoring and short-term individual-level dynamics. This advances the quantitative study of colony behavior, including daily rhythms, brood–adult relationships, and individual behaviors such as waggle dancing, while operating in naturalistic conditions without tags.

Literature Review

Prior work in social insect monitoring often uses physical tagging (including barcodes) to track individuals and has yielded insights into communication and information spread but suffers from practical limitations (manual effort, occlusions, inability to tag newly emerged bees without disruption). CNNs have transformed detection, pose estimation, and representation learning, primarily in human datasets, with fewer tools for dense insect collectives. In biological imaging, CNNs have been applied to cells/particles and to animal posture in small groups. Markerless identity approaches (“pixel personality,” idTracker/idtracker.ai) can work in less dense groups but require many isolated instances for training, which are rare in bee hives. A previous bee-specific markerless approach iteratively retrained a classifier but had limited accuracy and high computational cost. The present work builds on CNN segmentation (U-Net variants), leverages temporal information, and adopts triplet-loss embedding learning to exploit individual-specific visual signatures for dense, occlusion-prone tracking. It also relates to sociometry literature quantifying colony demography and rhythms, and to prior efforts in comb content classification under more standardized conditions.

Methodology

Data collection: Observation hives (47×47 cm, one-sided combs) were imaged at two locations with IR illumination (850 nm) and room temperature ~31°C. Cameras included a 5120×5120 px industrial camera (downsampled by 2×) and 4K cameras at 30 FPS. Long-term timelapse: five colonies (L1–L5) recorded for 2 weeks to 4 months (1–2 min sampling). Short-term videos: five colonies (S1–S5) at 30 FPS; 5-minute segments downsampled to 10 FPS for tracking.

Bee detection (segmentation+orientation): A modified U-Net includes a temporal prior by concatenating the penultimate layer from the preceding frame to the current pass, reducing parameters by ~94% versus original U-Net. Outputs: (1) 3-class segmentation (background, fully visible bees [full-bees], bees inside cells [cell-bees]); (2) orientation angle regression for full-bees with a sinusoidal loss. Labels mark bee centers with small elliptical/circular blobs to avoid overlap; class imbalance addressed by Gaussian weighting on bee regions. Postprocessing infers centroids, class, body axis, and orientation. Fine-tuning: initial predictions on a few frames per recording were manually corrected and used to retrain for adaptation.

Brood detection: Background images were generated over 12 h windows via motion-based background extraction. A standard U-Net was trained on circular foreground markers around labeled brood centers (weighted loss to balance classes) to detect capped brood cell centers.

Position-based matching: Initial trajectory assembly links detections frame-to-frame using Euclidean distance cutoffs that depend on posture (tighter for moving full-bees). A length factor biases matches toward extending longer trajectories. Greedy matching proceeds in ascending distance. Unmatched detections start new tracks. Gap handling: trajectories can bridge gaps up to 10 s if recently cell-bee heavy, 1 s near entrance, else 3 s; tracks shorter than 1 min are discarded. Parallelization splits sequences into 1-minute chunks for scalability.

Visual features (appearance embeddings) and triplet-loss training: Inception V3 was adapted with a triplet loss (margin 0.5) to learn 64-D embeddings that bring same-bee images closer than different-bee images. To make training tractable, triplets were sampled locally in space–time (where identity swaps occur), and hard triplets (nonzero loss) were recycled. Data augmentation included rotations/flips; background masking and angle-informed variants were tested. Training used 5000 epochs, Adam (lr=1e-4), batch size 32.

Matching with embeddings: For candidate matches within spatial cutoffs, visual similarity V is the minimum embedding distance to the recent history of a trajectory; candidates with V below a threshold (1.75) are considered. A combined score D = B·E + V + 1 (B=0.033; E includes the length factor) ranks matches. The same gap logic and parallelization apply. Angle-integrated variants were explored but did not improve accuracy.

Training/validation data: Four 5-min videos (S1–S4) were used to build an initial set of manually validated tracks (≥80% correct over minutes 1–4). These trained the first embedding model, which produced more tracks that were revalidated to form a final training set. Generalization was assessed on a fifth hive (S5) withheld from all training and via cross-validation (leave-one-hive-out).

Key Findings

Detection performance:

- Bee detection and orientation: errors ~10% of body width in position and ~10° in orientation; in held-out frames after fine-tuning, TPR ~0.99, FPR ~0.03, FNR ~0.01; orientation error comparable to human labelers.

- Brood detection: TPR ~0.99, FPR ~0.01, FNR < 0.01 in test frames.

Long-term sociometry:

- Clear ~24 h cycles in visible bee counts and especially in cell-bees across L1–L5.

- Strong negative correlation between visible bees and brood over 12 h windows during the first ~3 weeks (mean Pearson R^2 = 0.84, p < 0.0001).

- Cell-bees are predominantly elevated at night (21:00–06:00) and are located 7–14 mm closer to brood than other bees on average (Wilcoxon p < 0.0001 in L1–L4); proportion of cell-bees positively correlates with brood in L3–L5 (R^2 > 0.4, p < 0.05).

- Two colonies (L3, L5) showed declines; both had lower proportions of cell-bees and larger distances from brood, consistent with altered or unhealthy dynamics.

Tracking performance and dynamics:

- Appearance-augmented matching substantially outperformed position-only and prior pixel-identity approaches, increasing the proportion of correct trajectories at low computational cost (~1 h per 5-min video on 4 GPUs/36-core CPU).

- Generalization: In unseen S5 (vibration and lighting flicker), 77% of detected bees were correctly tracked; cross-validation across hives yielded 70–86% correctly tracked bees. Across S1–S5, ~79% of bee trajectories were recovered over 5 minutes.

- Behavioral signatures: Distributions of speed and angular speed varied across colonies; S2 and S5 had more fast and high-angular-speed individuals. High-angular-speed trajectories localized near the entrance (~2.5× more likely within 10 cm; p < 0.001), consistent with waggle dances. Manual inspection confirmed dancers/followers had higher motion velocities (N=10, p ~ 0.003; N=27, p ~ 0.025). High linear/low angular motion suggested patrolling; high comb-cell visits indicated cleaning/searching behaviors.

Discussion

The study demonstrates that CNN-based detection augmented with temporal priors and embedding-based visual similarity enables markerless, colony-wide tracking in a dense, occlusion-rich environment. High-accuracy detection of bees and brood supports continuous sociometric analyses revealing daily rhythms, brood–adult anticorrelation, and night-time increases of bees inside cells, as well as spatial coupling between cell-bees and brood. Embedding-driven tracking stitches detections across occlusions and contacts, generalizes to new hives, and uncovers individual behaviors such as waggle dances and comb-cell exploration. These results validate that pixel-level visual signatures can be leveraged without requiring long collision-free training segments, addressing a key obstacle in dense collectives. The findings open avenues for integrating short-timescale behavior with long-term colony demography to assess colony health and for expanding quantitative models of collective dynamics. The approach is complementary to tag-based systems, extending coverage to untaggable or occluded individuals and reducing disruption, while being compatible with additional sensors for comprehensive hive surveillance.

Conclusion

This work introduces a unified markerless pipeline for entire-colony analysis: (1) a temporally informed U-Net for bee detection with orientation and within-cell states; (2) a brood detection method from background-extracted images; and (3) a triplet-loss embedding approach for appearance-augmented tracking. The system achieves near-human detection accuracy, robust generalization across hives, and recovery of ~79% trajectories over 5 minutes, enabling discovery of circadian sociometric patterns, brood–adult relationships, and key behaviors (waggle dances, patrolling, cell cleaning). Future directions include extending tracking durations and reidentification across exits/entries by combining appearance with learned motion models (e.g., recurrent networks), incorporating two-sided hives, enhancing brood/comb content detection (eggs, larvae, honey/pollen) via improved lighting and temporal priors, and scaling to multiple colonies and other dense insect collectives.

Limitations

- Tracking window limited to 5 minutes for validated accuracy; reidentification after leaving and re-entering the hive is not yet supported.

- Brood/comb content detection currently limited to capped brood; eggs, larvae, honey, pollen were not detected due to imaging/background extraction constraints.

- Performance depends on imaging quality (IR lighting, resolution); challenging conditions (vibration, flicker) reduce but do not eliminate accuracy.

- Angle-integrated and background-masked embedding variants did not improve tracking; data augmentation increased data complexity and hindered convergence.

- One-sided observation hive may not capture full colony dynamics; extending to two sides will complicate identity maintenance across sides.

- Manual validation used to curate training trajectories; fully automated large-scale validation remains future work.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.