Medicine and Health

Invadopodia enable cooperative invasion and metastasis of breast cancer cells

L. Perrin, E. Belova, et al.

This study reveals how different cancer clones work together to invade and metastasize, showcasing the vital role of invadopodia in leader cells. Conducted by Louisiane Perrin, Elizaveta Belova, Battuya Bayarmagnai, Erkan Tüzel, and Bojana Gligorijevic, the research highlights the intriguing dynamics of breast cancer cell lines during invasion.

~3 min • Beginner • English

Introduction

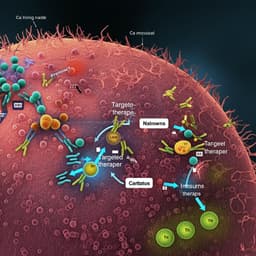

Metastasis causes the majority of cancer-related deaths, and in breast cancer, polyclonal metastases suggest collective dissemination of heterogeneous tumor cell clusters. Acquisition of invasive properties involves motility, extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation, and often epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Invadopodia—actin-rich, MMP-enriched protrusions—mediate local ECM degradation and are associated with high metastatic potential. Leader-follower heterogeneity during collective invasion implies that leader cells display higher contractility, cell-ECM adhesion, ECM remodeling and degradation, potentially via invadopodia. Yet, how spatial reorganization precedes cooperative invasion and whether cooperation extends to dissemination and metastasis remain unclear. This study investigates how cancer clones with differential invasive abilities cooperate during invasion and metastasis, focusing on the roles of persistence, cell-ECM interactions, E-cadherin-mediated adhesion, and invadopodia.

Literature Review

Prior work indicates that breast cancer metastases can arise from polyclonal, collectively disseminated clusters. Collective invasion involves phenotypically distinct leaders and followers; leaders show increased contractility, adhesion to ECM, remodeling and proteolysis. Invadopodia drive localized ECM degradation and correlate with metastasis, and their activity peaks in G1 phase. EMT is non-binary and may produce divergent invasive phenotypes; Twist-regulated programs can promote invadopodia. Previous 3D studies demonstrated cooperative invasion but did not delineate preceding spatial reorganization or test cooperation during metastasis. The differential adhesion hypothesis (stronger intercellular adhesions drive central positioning) often explains sorting in development, but its applicability to cancer spheroids is debated; motility differences and binary ECM interactions have been implicated in sorting in engineered tissues. Heterotypic E-/N-cadherin adhesions have been shown to mediate fibroblast–cancer cooperative invasion, but their role in cancer–cancer cooperation is uncertain.

Methodology

- Cell models: Isogenic murine breast cancer lines 4T1 (metastatic) and 67NR (non-metastatic); human MDA-MB-231 line and its Tks5 knockdown variant. Generation of fluorescently labeled lines (4T1-mScarlet, 67NR-GFP). Stable shRNA knockdowns: Tks5 (invadopodia scaffold) and E-cadherin (two KD efficiencies), with matched controls.

- 3D spheroid invasion assays: Hanging-drop (4T1/67NR) or low-adhesion V-bottom with Matrigel (MDA-MB-231) to form spheroids. Embedding in dense collagen I (5 mg/mL). Drug treatments: pan-MMP inhibitor GM6001 (25 µM), ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (10 µM), and mitomycin C for proliferation control. Longitudinal daily imaging and time-lapse confocal microscopy.

- Metrics of spatial organization and motility: Defined Distance Index (DI = distance from spheroid center/semimajor axis). Defined ADI (final DI − initial DI) to quantify net radial motion. Polar-coordinate mean squared displacement (MSD) analysis in radial and angular directions; extracted power-law exponents (α) and time-dependent effective diffusion coefficients.

- Invadopodia assays: Western blots for Tks5 and cortactin; 2D fluorescent gelatin degradation assay (Alexa-405–gelatin) to quantify per-cell degradation; spheroid labeling for Tks5, F-actin, and MMP-cleaved collagen I (Col-3/4) to identify functional invadopodia in leaders.

- Cell-ECM interaction tests: Mixed spheroids embedded in non-adhesive agarose vs collagen I to assess sorting dependence on ECM adhesivity. 2D cell-ECM adhesive competition assay using gelatin islands surrounded by poly-L-lysine (PLL) to score preference; live-cell tracking of boundary-crossing. Contact angle measurements on gelatin vs PLL as proxy for adhesion strength. Western blot for FAK and p-FAK.

- Cell-cell adhesion perturbations: E-cadherin blocking antibody treatment; generation of Ecadherin KD lines; assessment of invasion mode (strands vs single cells) and cooperative invasion with 67NR.

- Cooperative invasion setups: Mixed spheroids at various ratios (commonly 1:50 leaders:followers). Alternative setup embedding 67NR spheroids within collagen populated by dispersed 4T1 cells; conditioned medium controls to test soluble factor effects.

- In vivo metastasis assays: Orthotopic mammary fat pad injections in mice with single lines or mixtures (e.g., 1:300 4T1:67NR; 1:1 Tks5-CTL:Tks5-KD or MDA-MB-231 control:KD). When tumors reached 6–12 mm, lungs were harvested for clonogenic assays under selective antibiotics to attribute colonies to specific cell types. Tumor sections imaged to verify presence of both cell types.

- Statistics: Normality by Shapiro–Wilk; t-tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum as appropriate; significance thresholds p<0.05, 0.01, 0.001. Imaging and analysis details and code provided (GitHub, Zenodo).

Key Findings

- 4T1 exhibit MMP-dependent collective invasion into dense collagen I; 67NR do not invade. GM6001 blocks 4T1 invasion; mitomycin C shows invasion is not due to proliferation. E-cadherin maintained at 4T1 junctions during invasion.

- Invadopodia: 4T1 and 67NR express cortactin and Tks5, but only 4T1 degrade gelatin and show mature invadopodia (co-localized Tks5, F-actin, degradation). 67NR form invadopodia precursors but lack maturation/function. In spheroids, leader 4T1 cells show functional invadopodia co-localized with MMP-cleaved collagen I.

- Motility differences: In 2D scratch assay, 67NR move faster instantaneously, but 4T1 show significantly higher persistence (speed p=1.17×10−13; persistence p<2.20×10−16).

- Cell sorting precedes invasion: In mixed spheroids (1:50), 4T1 accumulate at the spheroid–collagen interface by day 3–4; DI of 4T1 increases and exceeds 67NR (p=1.32×10−14 and <2.20×10−16). Sorting is blocked by ROCK inhibitor or GM6001, implicating contractility and MMP activity.

- Mechanism of sorting: Time-lapse shows 4T1 in core move outward (higher ADI than edge-initial cells), whereas 67NR remain within compartments. MSD analysis reveals 4T1 super-diffusive radial motion (α>1) vs 67NR diffusive (α≈1), with similar angular motility. GM6001 reduces radial motility and effective diffusion coefficients.

- Sorting is E-cadherin independent: Blocking E-cadherin delays but does not prevent sorting. Stable E-cadherin knockdowns (36% and ~97% reduction) still sort to the edge by day 3.

- Adhesive ECM interface is required for sorting: In non-adhesive agarose, no sorting occurs; 4T1 at the edge migrate back into core (negative ADI for edge-initial cells). Despite maintained persistence differences, absence of adhesive interface prevents stable edge accumulation.

- ECM adhesion preference: In 2D competition, 85% of cells exiting gelatin onto PLL are 67NR, indicating 4T1 prefer gelatin. 4T1 show lower contact angle on PLL (reduced spreading/adhesion) compared to gelatin, whereas 67NR contact angle is similar on both. 4T1 express higher FAK and p-FAK, consistent with stronger ECM sensitivity.

- Cooperative invasion: In mixed spheroids, 67NR enter collagen I along with 4T1 leaders; number of strands per spheroid and fraction containing 67NR increase (p=1.90×10−7 and 9.86×10−6). Majority of strands are led by 4T1; GM6001 abrogates cooperative invasion. Microtracks in collagen are occupied by 4T1 leading and 67NR following. No heterotypic E-/N-cadherin junctions detected between 4T1 and 67NR.

- Role of E-cadherin in invasion mode: E-cadherin KD induces shift toward single-cell invasion (complete in KD2). Cooperative invasion requires strand formation; when leaders invade solely as single cells (Ecad-KD2), follower 67NR do not cooperatively invade.

- Invadopodia are required in leaders but not followers: Tks5-KD 4T1 lose invadopodia function and invasiveness (gelatin degradation p<2.2×10−16). In mixed spheroids (Tks5-CTL:Tks5-KD, 1:1), non-invasive Tks5-KD follow Tks5-CTL into collagen; most strands contain both and are led by Tks5-CTL. Human MDA-MB-231 models show similar results. Mixed Tks5-KD with 67NR do not form invasive strands, underscoring leader invadopodia necessity.

- In vivo metastasis: 4T1 and MDA-MB-231 controls form lung colonies; 67NR and Tks5-KD do not. Co-injection 4T1+67NR does not yield 67NR lung colonies. Co-injection Tks5-CTL+Tks5-KD results in lung colonies from both cell types, indicating cooperative metastasis dependent on invadopodia presence in leaders. Mixed MDA-MB-231 control with Tks5-KD shows only control metastasizes.

Discussion

The study addresses how heterogeneous cancer clones cooperate during invasion and metastasis. Differential persistence and sensitivity to adhesive ECM drive sorting, with invasive, persistent cells (4T1) accumulating at the spheroid–matrix interface. This spatial organization accelerates cooperative invasion, where leaders degrade ECM and carve microtracks that enable non-invasive followers to enter dense matrices. Sorting is not driven by differential intercellular adhesions; instead, MMP activity, contractility, and ECM adhesivity/persistence govern leader positioning. Functionally, invadopodia are a hallmark of leader cells: removing invadopodia (Tks5 knockdown) abolishes their ability to lead but not to follow in cooperative invasion. In vivo, mixtures of cells with and without invadopodia can metastasize cooperatively, provided leaders retain invadopodia; however, cooperative metastasis depends on strong E-cadherin-based cell-cell interactions (observed in 4T1 background) likely required for transient transendothelial migration, whereas cooperative invasion in collagen does not strictly require E-cadherin. These findings refine the understanding of leader-follower dynamics, positioning invadopodia as central to leader function and highlighting ECM-dependent motility as the driver of pre-invasive spatial reorganization.

Conclusion

- Invasive breast cancer cells with functional invadopodia (4T1) sort to the spheroid–ECM interface via persistent, ECM-sensitive motility and lead non-invasive cells (67NR) into collagen through MMP-dependent microtracks.

- Sorting is independent of E-cadherin-mediated adhesions but requires an adhesive ECM interface; invadopodia are specifically required in leader, not follower, cells.

- In vivo, cells lacking invadopodia can metastasize cooperatively when co-injected with invadopodia-competent cells, indicating invadopodia-enabled cooperative metastasis; this cooperation appears to require strong E-cadherin-mediated junctions for transendothelial transit.

- Therapeutically, targeting invadopodia could suppress both solitary and cooperative modes of metastasis.

Future directions include dissecting the molecular determinants that enable invadopodia maturation (e.g., MMP14 trafficking/activation), clarifying the interplay among cell cycle state, cellular energetics, and invadopodia in leader identity, and defining adhesion requirements for cooperative intravasation/extravasation across diverse tumor contexts.

Limitations

- Findings are based on specific murine (4T1/67NR) and human (MDA-MB-231) breast cancer models; generalizability to other cancers and microenvironments remains to be established.

- While 67NR display invadopodia precursors, the molecular basis of their maturation failure (e.g., MT1-MMP delivery/activation) was not directly tested.

- Sorting is shown to rely on ECM adhesivity and motility persistence, but the precise molecular regulators of ECM sensitivity and persistence differences (beyond FAK activation) were not fully delineated.

- Cooperative metastasis required E-cadherin in the tested contexts; the mechanistic basis of E-cadherin dependence for transendothelial migration of clusters was inferred but not directly visualized in vivo.

- Spheroid and collagen I assays model aspects of tumor invasion but may not capture full in vivo ECM complexity; agarose as non-adhesive control lacks biochemical cues.

- Interactions with stromal cells (e.g., macrophages, fibroblasts) and immune components were not incorporated, which can influence invasion and metastasis.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.