Physics

Direct observation of hot-electron-enhanced thermoelectric effects in silicon nanodevices

H. Xue, R. Qian, et al.

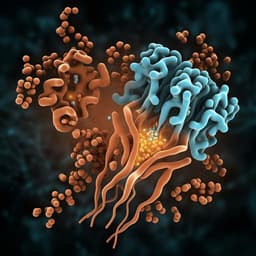

As silicon devices are downscaled, electrons are driven far from thermal equilibrium with the lattice, attaining much higher effective electron temperatures (Te) than the lattice (Tl). The relaxation of densely integrated electron hotspots imposes severe heat loads that limit device performance, making thermal management an urgent challenge in post-Moore nanoelectronics. Conventional passive cooling, reliant on material thermal conductance and constrained by interfacial thermal resistances, becomes less effective at the nanoscale. Consequently, alternative active cooling strategies that transcend material property limits are needed to manage localized heating in advanced silicon technology.

Active thermoelectric (TE) cooling generates heat flow via the Peltier effect (Q = ΠI) and is well established macroscopically under local thermal equilibrium (LTE), where Π ≈ ST and TE signals scale linearly with current. Practical TE modules typically use dissimilar materials to exploit Seebeck coefficient gradients at interfaces. However, nanoscale conditions can violate LTE because Te can significantly exceed Tl and hotspots produce extreme temperature gradients and current densities. Theoretical works on nonequilibrium TE in semiconductors predict that the Peltier coefficient should be defined with respect to Te, leading to nonlinear current dependence (Π acquiring higher-order terms, e.g., Π ∝ I^2), potentially enhancing cooling under high fields. Experimental observations of such nonlinear features have been scarce due to the difficulty of electron nanothermometry. Recent related phenomena in single-material nanostructures (e.g., graphene) under high fields were attributed to hot-carrier effects, but direct evidence of hot electrons and quantitative redefinition of Π under nonequilibrium remained lacking. This study addresses these gaps in silicon, the dominant semiconductor for integrated circuits.

Device architecture: Phosphorus-doped (n-type) silicon films (~90 nm thick, doping ~1×10^19 cm^-3) were epitaxially grown on high-resistivity Si substrates. Nanoconstrictions with a narrowest width of ~400 nm were patterned and etched to ~120 nm depth (deeper than the doped film) to confine current within the epitaxial layer. Ohmic contacts yielded linear I–V characteristics. AFM verified surface smoothness and etch profiles. Measurements were at ambient conditions (~300 K, atmospheric pressure). Nanothermometry: Two complementary techniques probed electron and lattice temperatures separately over identical scan areas:

- Scanning Noise Microscopy (SNoiM): A noncontact, radiative electronic nanothermometry detecting near-field evanescent electromagnetic fluctuations (~20.7±1.2 THz) from hot-electron shot noise to obtain Te maps. Absolute Te values were derived from signal intensity without adjustable parameters. Spatial resolution ~50 nm. External pulsed bias at ~5 Hz was used for demodulation.

- Scanning Thermal Microscopy (SThM): Contact thermocouple-based probes mapped the lattice temperature Tl. The probe sensitivity was calibrated at 13 µV/K. The device was excited by AC or pulsed voltages (typical f_exc ≈ 413 Hz). Lock-in detection captured thermal signals with high sensitivity; spatial resolution ~50 nm. Decoupling Joule and thermoelectric signals: To separate Joule heating from thermoelectric (TE) cooling/heating contributions in Tl maps, the device was driven with different waveforms and lock-in demodulation:

- Sinusoidal bias: Second-harmonic demodulation isolated Joule heating.

- Square-wave bias: First-harmonic demodulation isolated TE signals. Phase imaging (φ) determined the sign of TE cooling (negative) vs heating (positive), revealing a 180° phase change at the constriction center where ΔT_TE changes sign. Signal magnitudes were defined as: Joule = peak ΔT_Joule; TE = average of the absolute maxima at the cooling and heating peaks. Harmonic analysis under sinusoidal drive: With current I(t)=I0 sin(ωt), the measured dependencies (ΔTe ∝ I^2, hence ∝ sin^2 ωt) predict TE signals ΔT_TE ∝ Te J ∝ I×I×sin^2(ωt), leading via Fourier decomposition to components at f and 3f with a 3:1 amplitude ratio and a 180° phase inversion for the 3f component. Lock-in detection at 1f and 3f verified these predictions. Numerical modeling: A three-dimensional finite-element two-temperature model (TTM) was employed under steady state, treating electron and lattice subsystems with mutual energy exchange via electron–phonon coupling. Assumptions included: decouplable electron/lattice subsystems; classical transport with modified effective thermal conductivities to account for non-Fourier nanoscale effects; isotropic heat diffusion; and neglect of detailed phonon modal dynamics. The governing heat transport included Joule heating and electron–phonon scattering; TE terms were neglected in a first-order step to extract Te(r) and Tl(r). Using theoretical considerations, the nonequilibrium Peltier coefficient was taken to be governed by local electron temperature, Π(r) ≈ kB Te(r), appropriate for the degenerate, highly doped regime. With Te(r) known, TE contributions were computed from the -∇·(ΠJ) term to generate simulated Joule and TE profiles for direct comparison with experiments. Data analysis: 2D temperature maps were reduced to 1D line profiles along the channel to compare hotspot widths, positions, and asymmetries. Bias-dependent trends (4–10 V) were fitted to extract scaling laws: ΔT_Joule ∝ I^2 and ΔT_TE ∝ I^3. Ratios of TE to Joule signals vs bias were evaluated. Phase maps corroborated spatial sign changes of TE effects. Additional control assessments estimated conventional Thomson contributions using literature values for Si and assessed potential boundary-scattering and interfacial mechanisms.

- Clear nonequilibrium between electron and lattice subsystems: At 10 V bias, peak Te ≈ 1500–1596 K (ΔTe ~1200 K above room temperature) while Tl peaks near ~320–325 K (ΔTl ~20 K), confirming Te >> Tl.

- Extremely large electron-temperature gradients near the constriction (~1 K/nm) coincide with localized hotspots; Te peaks are sharper and narrower than Tl peaks.

- Spatial thermoelectric signatures directly imaged: TE cooling and heating lobes appear on opposite sides of the constriction, with a sharp node (ΔT_TE = 0) at the center and a 180° phase flip across the node; reversing current swaps cooling/heating sides.

- Quantitative magnitudes at 10 V: ΔT_TE up to ±1.3 K; ΔT_Joule ~18 K. TE amplitude is ~7% of Joule heating at 10 V, explaining modest asymmetry in total Tl maps.

- Scaling with current (or bias): Joule heating follows ΔT_Joule ∝ I^2 (Joule–Lenz law). TE signals follow a cubic dependence, ΔT_TE ∝ I^3, consistent with nonequilibrium Peltier effects where Π depends on Te. Consequently, the TE/Joule ratio increases approximately linearly with bias.

- Harmonic content under sinusoidal drive: TE signals contain fundamental (f) and third-harmonic (3f) components with similar spatial profiles; the 1f peak is ~3–4 times the 3f peak, and the 3f component exhibits opposite sign, matching ΔT_TE ∝ 3 sin(ωt) − sin(3ωt).

- Simulations corroborate experiments: Two-temperature finite-element modeling reproduces Te and Tl profiles (including Te ~1596 K and Tl ~325 K at 10 V), TE spatial patterns, current scalings (quadratic for Joule, cubic for TE), and the linear growth of TE/Joule ratio with bias, supporting Π(r) ≈ kB Te(r) under nonequilibrium.

- Conventional mechanisms insufficient: Estimated classical Thomson contribution is ~4% of observed TE; boundary scattering effects are minor given device dimensions vs mean free path; no bi-material interfaces exclude energy filtering/thermionic mechanisms.

The core question was whether nonequilibrium hot electrons in silicon can enhance thermoelectric effects and how the Peltier coefficient behaves under Te ≠ Tl. Direct, spatially resolved measurements of Te and Tl show pronounced electron–lattice nonequilibrium with sharp Te hotspots and large ∇Te near a Si nanoconstriction. The observed TE cooling/heating patterns, their current-direction dependence, and the cubic scaling of the TE amplitude with current substantiate a nonequilibrium Peltier effect where Π is governed by Te rather than Tl. Mechanistically, hot electrons serve as energy carriers: they absorb energy from the lattice while climbing the Te profile at the entrance side (Peltier cooling) and release energy on the exit side (Peltier heating). The TE term arises from -∇·(ΠJ), and with Π ∝ Te and ΔTe ∝ I^2, the net TE temperature response scales as I^3, in agreement with both harmonic analysis and finite-element simulations using a two-temperature framework. Alternative explanations—classical Thomson effect under LTE, boundary-scattering-modified Seebeck coefficients, or interface-related energy filtering/thermionic emission—cannot account for the magnitude, spatial signatures, and cubic scaling observed. These findings validate the nonequilibrium redefinition of the Peltier coefficient in silicon nanodevices and highlight hot-electron transport as a lever to enhance nanoscale thermoelectric performance for on-chip cooling.

This work provides direct experimental evidence of hot-electron–enhanced thermoelectric effects in silicon nanoconstrictions by separately imaging electron and lattice temperatures. It demonstrates that under strong nonequilibrium (Te >> Tl), the Peltier coefficient is governed by electron temperature, leading to a thermoelectric response that scales cubically with current. Finite-element two-temperature simulations, incorporating Π(r) ≈ kB Te(r), quantitatively reproduce the spatial maps, amplitudes, and scaling laws, confirming the nonequilibrium thermoelectric mechanism. Although TE signals are smaller than Joule heating at moderate bias, their faster growth with bias indicates a viable path to active nanoscale cooling leveraging hot carriers in silicon-compatible architectures. Future work could pursue strategies to further amplify nonequilibrium TE effects, including laser-spot-induced temperature gradients, intervalley-assisted energy transport, and spin-Peltier effects, as well as integrate device engineering to optimize constriction geometry and material parameters for enhanced on-chip refrigeration.

- Relative magnitude: TE cooling/heating is ~7% of Joule heating at 10 V, so net cooling is modest under the studied conditions.

- Modeling assumptions: The two-temperature model assumes decouplable electron and lattice subsystems, isotropic heat diffusion, and uses effective (modified) thermal conductivities without detailed phonon-mode dynamics; TE terms were initially neglected to extract Te(r) before inclusion, which may omit higher-order couplings.

- Phonon dynamics: Possible directional phonon emission during electron–phonon scattering could influence results; its role in preserving cubic scaling remains an open theoretical question.

- Boundary and geometry effects: While boundary scattering is argued to be minor given sizes vs mean free paths, different geometries or smaller dimensions may alter Seebeck and transport properties.

- Measurement uncertainties: Reported uncertainties include ~20 mK for ΔT_TE from SThM and ~100 K Te fluctuation from SNoiM noise; absolute calibration and spatial resolution (~50 nm) limit precision near steep gradients.

- Generalizability: Results pertain to highly doped (~1×10^19 cm^-3) thin-film Si nanoconstrictions at room temperature; extrapolation to other doping levels, temperatures, or device architectures requires further study.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.