Health and Fitness

Attaching protein-adsorbing silica particles to the surface of cotton substrates for bioaerosol capture including SARS-CoV-2

K. Collings, C. Boisdon, et al.

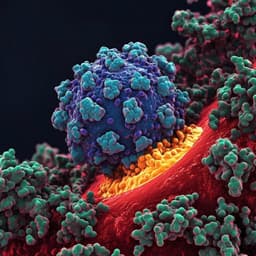

The study addresses the challenge of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and the limitations of widely used fabric face coverings such as cotton, which are popular for comfort and breathability but often provide limited filtration efficiency. With shortages of surgical and N95 masks during the COVID-19 pandemic and concerns over breathability and reusability, the authors seek to enhance the performance of cotton-based coverings without compromising comfort. They hypothesize that amorphous mesoporous silica microspheres, known to strongly adsorb proteins, can be attached to cotton fibers to effectively capture bioaerosols, including SARS-CoV-2, via interactions with viral surface proteins (spike). The goal is to design a face covering that combines high filtration efficiency for biologically relevant aerosols with minimal pressure drop (good breathability).

Prior work has shown varied performance of homemade and commercial masks, with cotton materials offering moderate filtration but good comfort. Studies highlight that mask design, materials, and electrostatic or surface interactions influence filtration, and some N95 respirators with valves can reduce filtration efficiency relative to valveless designs. Numerous innovations have been reported to improve mask performance, including antimicrobial coatings, incorporation of pathogen-inactivating metal-based particles, photocatalytic and thermal sterilization approaches, and surface wettability engineering (superhydrophilic/hydrophobic materials). Silica has a long history in protein purification and as a stationary phase in liquid chromatography, where proteins tend to adsorb strongly to silica due to hydrophilic/hydrophobic patch interactions and electrostatics; adsorption can be modulated by salts and organic solvents. Given coronaviruses’ lipid envelope bearing spike proteins and the general propensity of proteins to adsorb at interfaces, amorphous mesoporous silica presents a promising platform for capturing bioaerosols via adsorption mechanisms.

Materials and silica synthesis: Amorphous mesoporous spherical silica particles were synthesized via a Stöber-type process by hydrolyzing and condensing TEOS in ammonium hydroxide with isopropanol co-solvent and dodecylamine template, followed by washing and drying. Surface derivatization with a quaternary amine (QA) ligand was performed using N-trimethoxysilylpropyl-N,N,N-trimethylammonium chloride (TMAPS) in dry toluene under reflux to activate the QA functionality. Particle characteristics included a diameter ~50 μm selected for inhalation safety, and mesoporosity with non-functionalized silica having surface area 302.24 m²/g, mean pore volume 0.96 cm³/g, and mean pore diameter 11.8 nm. Pore sizes <10 nm were targeted in design to draw smaller analytes into pores by capillarity while leaving larger viral particles adsorbed on the outer surface. Heat treatment (800 °C) was used to dehydroxylate and alter surface chemistry for mechanistic controls. Zeta potentials were measured; QA-functionalized silica exhibited an average positive zeta potential (+15.6 mV). Heat treatment increased positive zeta potential due to surface silanol rearrangement.

Substrate preparation and bonding: Two non-woven 4-layer cotton swab variants (5 × 5 cm) served as substrates. QA-functionalized silica (13 mg per 5 × 5 cm swab) was deposited from 10% methanol in water with agitation; swabs were oven-dried at 150 °C for ≥30 min to remove solvent and promote bonding. Bonding occurs via condensation between silica silanols (Si–OH) and cellulose hydroxyls (C–OH) to form Si–O–C linkages under thermal treatment. SEM confirmed even distribution of QA-functionalized silica on fibers; preliminary stability tests indicated retained silica under ambient storage and high-flow testing.

Aerosol generation and characterization: An ultrasonic nebulizer generated aerosols of test solutions. Particle size distributions were measured with a handheld laser particle counter across analytes (water; cytochrome c, myoglobin, ubiquitin, BSA; inactivated SARS-CoV-2 at 1.3 × 10^6 PFU/mL; creatinine; caffeine). All showed similar distributions with most frequent diameter ~0.3 μm and most particles <1 μm.

Filtration efficiency test setup: A custom test rig (adapted from TU Delft specifications) drew nebulized aerosols through a clamped circular sample (2 cm diameter) of the material under test. Air was sampled immediately before (BMC) and after (AMC) the material through PTFE syringe filters (0.22 μm) at 10 mL/min for protein experiments, enabling calculation of filtration efficiency as (BMC − AMC)/BMC × 100%. For proteins (cytochrome c, myoglobin, ubiquitin, BSA; 1 mg/mL in water), captured analyte on syringe filters was extracted and quantified by mass spectrometry. For inactivated SARS-CoV-2, 1 mL of suspension was nebulized per experiment; downstream capture used 13 mm syringe filters, followed by extraction into 0.4 mL of lateral flow assay (FlowFlex) extraction fluid; 0.1 mL was applied to test strips, incubated 30 min, imaged (GelDoc Go), and quantified using a calibration curve (1.3 × 10^1–6.5 × 10^3 PFU/mL). LFA signal saturation above ~7 × 10^1 PFU/mL was addressed by dilution of extracts.

Breathability and quality factor: Differential pressure (pressure drop) across materials was measured with a pressure sensor at increasing air flow rates; key comparison at 85 L/min (NIOSH standard). Filter quality factor (QF) was computed as −log10(FE/100)/ΔP (ΔP in kPa), using cytochrome c FE.

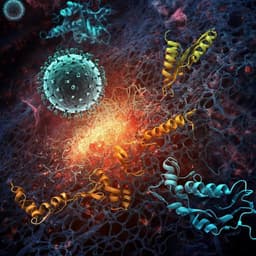

Mechanism experiments: To isolate capture mechanisms, aerosols were passed through beds of silica (0.2 g) held in stainless-steel meshes in a custom chamber. Two silica variants were tested: QA-functionalized (as used on cotton) and heat-treated (800 °C) unfunctionalized silica (reduced silanol content). After exposure to nebulized BSA (1 mg/mL), silica was washed, protein eluted with 100% methanol, and extracts analyzed by MS. A liquid-phase control incubated BSA (0.01 mg/mL) with each silica variant (0.05 g, 1 h) prior to MS to compare retention behavior.

Comparators: Three materials were evaluated in filtration and breathability tests: silica-coated cotton, blank cotton substrate (no silica), and a commercially available 2-layer 100% cotton face covering (Earth Square, UK). All tests were performed in a fume hood; the silica used was amorphous.

- Silica-coated cotton exhibited substantially higher filtration efficiencies for aerosolized analytes versus controls.

- Proteins: Example data for cytochrome c showed filtration efficiencies of 95 ± 2% (silica-coated), 78 ± 5% (blank cotton), and 48 ± 3% (commercial cotton face covering). Other proteins (myoglobin, BSA, ubiquitin) similarly showed significantly improved capture with silica-coated material (n = 3; statistical tests indicated significant differences).

- Inactivated SARS-CoV-2: Filtration efficiency was 94.4 ± 0.4% for silica-coated cotton, 84.3 ± 3.6% for blank cotton, and 80.2 ± 2.1% for the commercial cotton face covering (n = 3; one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD). Corresponding after-mask concentrations (reported as ×10^1 PFU/mL) were 1.6 ± 0.4 (silica-coated), 4.6 ± 0.6 (blank), and 14.9 ± 2.2 (commercial cotton).

- Aerosol size distributions across all test solutions peaked around ~0.3 μm, with most particles <1 μm, confirming aerosolized conditions.

- Mechanistic test: QA-functionalized silica captured aerosolized protein approximately 10-fold more efficiently than heat-treated (dehydroxylated) silica of identical size and shape, demonstrating that surface chemistry (silanols/QA groups enabling electrostatic and hydrogen-bond interactions) is critical beyond physical interception.

- Breathability: Pressure drop at 85 L/min was 152 Pa (silica-coated), 143 Pa (blank), and 166 Pa (commercial cotton). The addition of silica increased pressure drop only slightly (+6.2% vs blank) and remained lower than the commercial cotton covering. Calculated filter quality factor (QF) using cytochrome c FE: 8.6 kPa^-1 (silica-coated), 2.0 kPa^-1 (blank), 1.7 kPa^-1 (commercial cotton).

- Zeta potential and surface characterization supported enhanced positive surface charge with QA functionalization and changes upon heat treatment consistent with altered adsorption behavior.

The results support the central hypothesis that mesoporous silica particles, when attached to cotton fibers and functionalized with a quaternary amine, enhance capture of bioaerosols primarily through adsorption interactions with proteins, including viral surface proteins. The silica-coated cotton consistently outperformed both unmodified cotton and a typical commercial cotton face covering in filtration tests for proteins and inactivated SARS-CoV-2, while maintaining comparable or better breathability. Mechanistic experiments indicate that the dominant capture mechanism is not purely physical interception but arises from surface chemistry—hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions between protein surfaces and silica/QA functional groups. The pore structure further contributes by drawing smaller molecules into pores while leaving larger viral particles to adsorb on the outer surface, increasing the effective capture area. Collectively, these findings show that integrating protein-adsorptive silica into common, comfortable substrates like cotton can deliver high filtration efficiency without undue pressure drop, addressing the need for accessible, breathable face coverings with improved bioaerosol capture during respiratory disease outbreaks.

This work demonstrates a simple, material-based strategy to enhance bioaerosol capture by attaching QA-functionalized mesoporous amorphous silica microspheres to cotton substrates. The resulting face covering achieved high filtration efficiencies (~94% for inactivated SARS-CoV-2; ~95% for cytochrome c) with minimal impact on breathability (152 Pa at 85 L/min) and a markedly improved filter quality factor over controls. Mechanistic studies indicate a primary role for adsorption driven by silica surface chemistry. These findings suggest that silica-functionalized textiles could be integrated into consumer face coverings or filtration devices to improve protection against airborne pathogens while preserving comfort. Future work should evaluate durability and reusability (e.g., washing/sterilization cycles), long-term stability and shedding under realistic use, performance against live viruses and broader bioaerosols, optimization of silica loading, pore size and surface chemistry, and assessment in standardized certification tests and real-world trials.

- The study used UV-inactivated SARS-CoV-2 and a semi-quantitative lateral flow assay with a known signal saturation threshold, necessitating sample dilutions; results may differ with live virus and quantitative virological assays.

- Laboratory test rig conditions (fume hood setup, idealized seal) may not fully represent real-world mask fit, leakage, and user behavior.

- Limited material set and geometries were tested (non-woven cotton swabs and one commercial cotton mask), without evaluation of multilayer configurations, other fabrics, or certified respirator formats.

- Durability, reusability, and cleaning/washing effects were not systematically assessed; stability testing was preliminary.

- While the silica was amorphous and particles were selected at ~50 μm to mitigate inhalation risk, comprehensive shedding and long-term safety assessments during extended wear were not reported.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.