Interdisciplinary Studies

A practical guideline how to tackle interdisciplinarity—A synthesis from a post-graduate group project

M. O. Kluger and G. Bartzke

The paper addresses how postgraduate researchers can effectively practice interdisciplinarity to tackle complex environmental problems, using coastal wind-farm siting as an exemplar. It situates the work within a broader shift toward interdisciplinary collaborations necessary for multifaceted challenges (e.g., climate change), and acknowledges that while interdisciplinarity is promoted by funders and institutions, practical integration often stalls at boundaries between closely related fields. The central aim is to extend existing scholarship by reflecting on a doctoral/postdoctoral group’s process of interdisciplinary integration across natural, social, and legal domains and to produce a practical guideline. The guiding research question the group formulated was: How do natural, social, and legal disciplines change in importance and interconnectivity when comparing potential wind farm locations (a) offshore within exclusive economic zone, (b) offshore within territorial sea, and (c) onshore near the coast? The purpose and importance lie in providing a feasible, structured approach for early-career researchers to build shared understanding and integrated outcomes across disparate disciplines.

The paper reviews scholarship highlighting the necessity and challenges of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research for complex problems, noting funder emphasis and graduate training initiatives (e.g., IGERT, Toolbox Dialogue Initiative). Prior works stress that breakthroughs occur at disciplinary boundaries but that IDR faces systemic hurdles (e.g., lower funding success, communication barriers, stereotypes). Models for integrative processes (e.g., Lang et al., 2012; Carew & Wickson, 2010) typically involve phases of problem framing, co-creation of knowledge, and application. Brown et al. (2015) emphasize principles like forging a shared mission and cultivating T-shaped researchers. The authors position their contribution as a practical extension of these models for postgraduate contexts, synthesizing concepts (group meetings, multidisciplinary subgroup work, off-campus retreat, interactivity via role play, and abstraction via conceptual modeling) to facilitate integration. The review also notes common pitfalls: asymmetries across natural vs. social/legal sciences, language and form differences, and prejudice or stereotypes affecting collaboration.

Design: A reflective case study of an 11-month interdisciplinary group project (Oct 2014–Sep 2015) within the INTERCOAST postgraduate program (University of Bremen and University of Waikato). Participants: 14 total (12 doctoral students, 2 postdoctoral researchers) spanning geosciences, biology, social sciences, and legal sciences (with a majority of geoscientists). The project unfolded in three phases.

Phase 1 (Months 1–9): Phrasing an integrated research question

- Monthly group meetings combining informal lunch breaks and 2-hour formal seminars organized by postdocs.

- Brainstorming to identify a common research problem relevant to the coastal environment; wind energy production selected via open vote.

- Individual literature reviews: each participant explored one aspect (e.g., noise emissions, public perception, sediment stability, regulatory frameworks) and presented in 10-minute talks followed by 30–60 minute discussions in seminars 2–6.

- Seminars 7–9 refined the scope and wording and agreed by open vote on the integrated research question comparing the importance and interconnectivity of natural, social, and legal disciplines across three locations (onshore near coast; offshore within territorial sea up to 12 nm; offshore within EEZ up to 200 nm).

Phase 2 (Month 10): Creating a common understanding

- Participants split into four multidisciplinary subgroups, each anchored by an expert from the focal discipline (natural, social, legal, biology), to prepare 30-minute group presentations addressing the integrated question.

- Subgroups presented during day 1 of a 2-day off-campus retreat; discussions focused on disciplinary concepts, vocabulary, methods, and values, with the goal of building shared understanding.

Phase 3 (Month 11): Establishing an interactive communication framework

- Role play (day 2 of the retreat): an open forum with assigned roles (e.g., local resident, wind farm operator, eco-activist, federal politician, maritime agency employee) moderated by a participant, to simulate stakeholder deliberation on siting a fictional wind farm.

- Post-retreat, two 6-hour seminars to reflect, synthesize, and construct a conceptual model capturing the relative weighting and interconnections among disciplines for each location.

Documentation and monitoring considerations

- Participation time and equal contribution were not formally tracked; subgroup composition was random and sometimes lacked all four disciplines. Decisions (topic selection, research question) used open discussion and votes. The process emphasized experiential learning and reflective synthesis rather than quantitative evaluation of participation.

-

Group composition and process

- 14 participants (12 PhD, 2 postdocs) from geosciences, biology, social sciences, and legal sciences; project duration 11 months.

- A three-phase integration process emerged: (1) comparing disciplines, (2) understanding disciplines, (3) thinking between disciplines.

- Informal lunch breaks fostered trust and gradual shift from discipline-centric to interdisciplinary conversations.

-

Integrated research question

- Final question: How do natural, social, and legal disciplines change in importance and interconnectivity across three wind farm locations: onshore near the coast, offshore within territorial sea, and offshore within EEZ?

-

Multidisciplinary subgroup insights (Phase 2)

- Onshore near coast: Geological and biological constraints considered comparatively lower due to anthropogenically modified settings; societal impacts (e.g., visibility, landowner/tourism concerns) comparatively high; legal frameworks important.

- Offshore territorial sea (≤12 nm): High geological and biological considerations (loads, subsoil properties, ecosystem effects); societal concerns elevated due to visibility from shore affecting acceptance and tourism; legal frameworks important.

- Offshore EEZ (≤200 nm): Geological/biological considerations remain high; societal impacts focused on shipping/fishery and generally lower public opposition due to distance; legal frameworks important.

- Legal aspects: Regulatory frameworks were considered equally important across all three domains.

- Interactions: Society–biology interactions weighted higher than society–geology, especially where wind farms are visible (onshore and territorial waters), reflecting public empathy with flora/fauna.

-

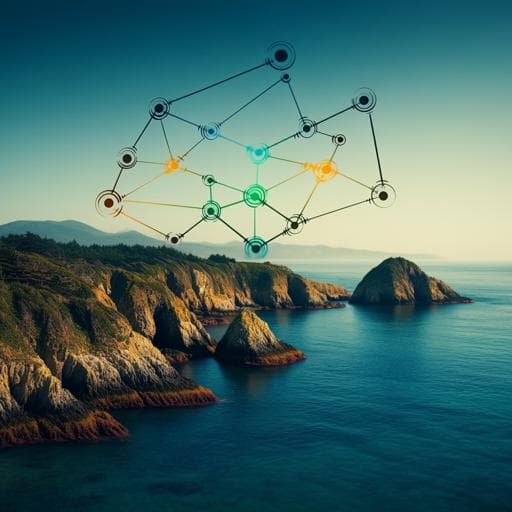

Conceptual model

- Law placed centrally (triangular “cogwheel”) mediating interactions among geology, biology, and society (circles). Circle sizes reflect disciplinary weighting per location; arrow widths depict interaction strengths. The model underwent iterative refinement and was accepted by all participants.

-

Practical guideline

- Synthesized a guideline aligning with but extending Lang et al. (2012), operationalized via five enabling concepts: group meetings (including informal/formal mix), multidisciplinary subgroup work, off-campus retreat, interactivity (role play), and abstraction (conceptual modeling).

- Development of T-shaped researchers was observed through experiential engagement and role play.

-

Communication challenges identified

- Language: differing definitions (e.g., “coast”) across colloquial, geological, and legal contexts.

- Form: divergent norms in visuals, quantification, footnotes, tone, and structure across disciplines.

- Prejudice/stereotypes: implicit hierarchies and disciplinary cultures required explicit reflection and trust-building.

The project directly addressed the integrated research question by eliciting and negotiating disciplinary weightings and interconnections for wind-farm siting across three spatial domains. Through staged exposure (individual reviews, subgroup work, retreat, role play) and structured reflection, participants translated diverse concepts and evidentiary standards into a shared conceptual model. Locational context mediated the salience of societal concerns (visibility, tourism, industry) while geological and biological considerations remained core offshore; legal frameworks consistently structured interactions and processes across all domains, justifying law’s central mediating role in the model.

The significance lies in operationalizing interdisciplinarity for early-career researchers through concrete mechanisms that cultivate mutual comprehension, empathy, and co-creation. The guideline complements existing transdisciplinary models by specifying actionable practices (e.g., informal-formal meeting cadence, role play, off-campus retreats) that scaffold movement from disciplinary comparison to interfacial, integrative thinking. It also responds to known barriers—terminological ambiguity, stylistic heterogeneity, and stereotypes—by creating time and social space to surface and reconcile differences. The resultant T-shaped capacities and shared abstractions (conceptual model) provide a transferable template for similarly complex socio-environmental problems.

This study contributes a practical, staged guideline for postgraduate interdisciplinary integration: (1) comparing disciplines to frame a shared integrated research question, (2) understanding disciplines through multidisciplinary subgroup work and peer presentations, and (3) thinking between disciplines via interactivity (role play) and abstraction (conceptual model). Applying this process to coastal wind-farm siting clarified how the importance and interconnectivity of natural, social, and legal disciplines vary across onshore, territorial sea, and EEZ contexts, with law serving as a central structuring framework and society–biology interactions particularly influential where installations are visible.

Main contributions

- A replicable process design with five enabling concepts (group meetings, subgroup work, off-campus retreat, interactivity, abstraction) tailored to postgraduate settings.

- An integrative conceptual model capturing disciplinary weightings and interactions by location, offering a diagnostic tool for planning and stakeholder engagement.

- Empirical insights into communication barriers and methods to cultivate T-shaped researchers and trust across disciplines.

Future directions

- Implement and evaluate the guideline in diverse settings and problem domains, with balanced disciplinary representation.

- Introduce iterative feedback loops between phases and formal metrics for participation and learning outcomes.

- Extend role-play formats to include real stakeholders and decision-makers; validate and refine the conceptual model against real-world projects and policies.

- Disciplinary imbalance: The group was dominated by natural sciences (geosciences), with fewer social and legal scientists, potentially biasing weighting and interactions during integration.

- Small, convenience sample: 14 participants from a single program limits generalizability.

- Participation monitoring: No tracking of time-on-task or equal contribution; subgroup composition was random and sometimes incomplete across disciplines.

- Process linearity: Phases followed a predefined sequence with limited iteration between phases; refinements largely occurred within phases.

- Communication challenges: Persistent issues in terminology, stylistic norms, and implicit disciplinary hierarchies may have affected discussions and outputs.

- Context specificity: Findings (e.g., societal acceptance patterns) reflect a German coastal context and a fictional case; transferability should be evaluated in other regions and real projects.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.