Health and Fitness

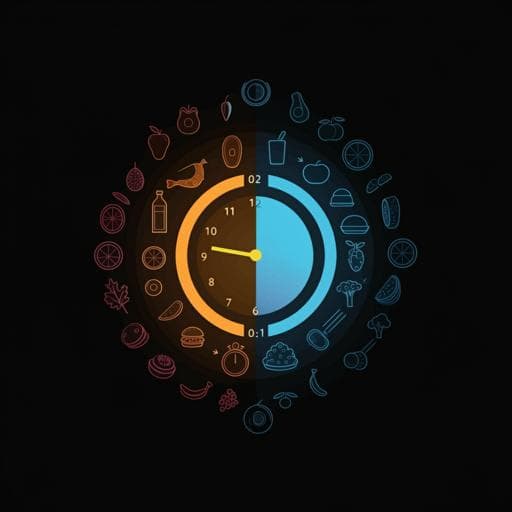

Night eating in timing, frequency, and food quality and risks of all-cause, cancer, and diabetes mortality: findings from national health and nutrition examination survey

P. Wang, Q. Tan, et al.

This study by Peng Wang and colleagues delves into the impact of night eating patterns on mortality risks, revealing that later timing and higher frequency of night eating can significantly increase all-cause and diabetes mortality. Interestingly, consuming low-energy-density foods earlier in the evening may counteract these risks.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.