Engineering and Technology

Nano-topology optimization for materials design with atom-by-atom control

C. Chen, D. C. Chrzan, et al.

Discover the groundbreaking "Nano-Topology Optimization (Nano-TO)" method developed by Chun-Teh Chen, Daryl C. Chrzan, and Grace X. Gu, enabling the design of nanostructured materials with unparalleled elastic properties. This innovative approach outperforms existing TPMS structures and the Hashin-Shtrikman upper bound, paving the way for novel materials without predetermined designs.

~3 min • Beginner • English

Introduction

The study addresses the long-standing challenge of designing materials with atomic-level precision, a vision articulated by Feynman but still unrealized due to the lack of both fabrication and computational design tools capable of atom-by-atom control. The authors propose Nano-Topology Optimization (Nano-TO), a de novo computational approach operating at the atomistic scale to directly manipulate individual atoms to optimize material properties. The work focuses on maximizing elastic properties, particularly the bulk modulus, in nanostructured aluminum, and investigates whether exploiting nanoscale surface effects can yield designs that surpass both commonly used TPMS architectures (e.g., gyroid) and theoretical bounds (Hashin-Shtrikman upper bound) derived for continuum two-phase composites.

Literature Review

The paper situates its contribution within several domains: (1) Additive manufacturing advances (e.g., two-photon lithography) enabling complex, multiscale architected materials and motivating computational design across scales. (2) Biomimicry-inspired material designs achieving enhanced strength, toughness, and impact resistance by emulating natural structures (nacre, conch shell, bone). (3) Mathematical designs based on triply periodic minimal surfaces (TPMS), notably the gyroid, extensively studied for mechanical, thermal, optical, and electromagnetic properties. (4) Machine learning for inverse materials design, promising but challenged by high-dimensional design spaces. (5) Continuum topology optimization (TO) as a mature approach for large-scale structural design but fundamentally limited to continuum discretizations (FEM), thus not directly applicable to atomistic design. This background highlights the gap that Nano-TO aims to fill: a method to perform topology optimization at the atomic scale capturing surface and coordination effects inaccessible to continuum methods.

Methodology

Nano-TO performs atomistic-scale topology optimization by toggling atoms between real (present) and virtual (removed) states to maximize a target property under a volume (density) constraint. Key components: (1) Design variables: Each atom i has x_i in {0,1}, with 1 = real, 0 = virtual. The atom type can switch during optimization. (2) Sensitivity analysis: The objective is the elastic strain energy under a prescribed external strain (e.g., hydrostatic for bulk modulus). Using a modified embedded-atom method (EAM) potential that integrates x_i into the total energy, the elastic strain energy difference between deformed and equilibrium states is approximated by pairwise contributions. The gradient with respect to x_k is approximated as twice the elastic strain energy associated with atom k for real atoms; virtual atoms have undefined raw sensitivities set to zero prior to filtering. (3) Sensitivity filtering: To provide meaningful sensitivities for virtual atoms and ensure mesh/atom-grid independence, a local weighted averaging within a neighborhood defined by filter radius r_min is applied. The filtered sensitivity for each atom incorporates neighboring atoms within r_min (chosen ~ the lattice constant). (4) Update scheme: Iteratively remove least-sensitive real atoms and admit most-sensitive virtual atoms. Two stages are used: Stage 1 reduces volume to a target volume fraction v by setting rejection rate > admission rate (e.g., reject 2, admit 1 per iteration); Stage 2 maintains volume by setting equal rates (e.g., reject 1, admit 1) until convergence. (5) Initialization and parameters: To avoid symmetry stagnation, an initial FCC aluminum unit cell (~4 nm, 4000 atoms) with periodic BCs in x, y, z begins with a single virtual atom as an imperfection. Aluminum is modeled with a Mishin-type EAM potential. Filter radius is ~4 Å (12 nearest neighbors). Target volume fractions are 50–80%. Random initialization strategy: Multiple runs from varied initial perturbations to locate strong local optima; 16 designs were generated for v=50%. (6) Objective instantiation: Maximizing bulk modulus K is cast as maximizing elastic strain energy under a constant hydrostatic strain. Periodic boundary conditions are applied to compute macroscopic elastic response (supercell homogenization). (7) Comparative structures and scaling: TPMS architectures (gyroid, Schwarz D/diamond, Schwarz P/primitive) are generated from level-set approximations; volume fraction controlled via threshold t. Structures with identical volume fractions are compared. Size effects are studied by parameterizing the Nano-TO design motif (BCC-arranged truncated octahedral vacancies) and TPMS across unit cell sizes from 4 to 64 nm. (8) Surface effect quantification: Separate atomistic nanoplate models with {111} free surfaces are constructed with in-plane periodicity ([110], [112]) and vacuum along [111] to obtain in-plane Young’s moduli as a function of layer count (3–48 layers). A bulk reference is created by removing vacuum and imposing periodicity along [111]. Strain–energy curves are computed for ±1e−2 strain. (9) Computation: Simulations performed in LAMMPS with modified EAM; visualization and atomic strain via OVITO. (10) Theoretical bounds: Hashin–Shtrikman (HS) upper bound for porous two-phase composites is computed using aluminum’s bulk and shear moduli, with G obtained from Voigt–Reuss–Hill averaging (G_avg ≈ 29.28 GPa). Anisotropy effects are bounded using extreme shear moduli (G_min = 26.12 GPa; G_max = 31.60 GPa) to confirm exceedance persists under anisotropy considerations.

Key Findings

- Nano-TO produced nanostructures (Al, FCC base) whose bulk moduli exceed TPMS counterparts and the HS upper bound at small cell sizes due to surface effects. For v=50% and 4 nm cell size, the best Nano-TO design achieved K = 22.20 GPa, exceeding the HS upper bound K_HS = 19.63 GPa. Over 16 randomized initializations at v=50%, K ranged 18.25–22.20 GPa (mean 20.95 GPa).

- Across volume fractions 50–80% (cell size 4 nm), Nano-TO designs consistently outperform gyroid, diamond, and primitive structures at the same v; TPMS are far from optimal for maximizing K.

- Size dependence: For the Nano-TO template and TPMS at v=50% with unit cell sizes 4–64 nm, K decreases with increasing size as surface-to-volume ratio drops. Nano-TO exceeds HS at small sizes (e.g., 4 nm) and approaches the HS upper bound as size increases (≥16 nm, surface effects negligible). Nano-TO remains superior to TPMS at all studied sizes.

- Load transfer: Under uniform hydrostatic strain −1e−2 and v=50%, cell size 16 nm, average atomic strains (compressive) ε_zz are larger in Nano-TO (−0.0048) than in gyroid (−0.0033), diamond (−0.0035), primitive (−0.0029), indicating better load transfer and higher stored elastic energy.

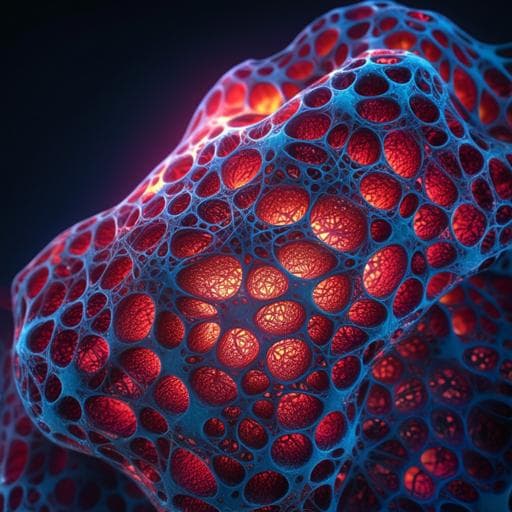

- Geometry and surfaces: Optimized designs are nearly cubic symmetric; virtual atoms form BCC-arranged truncated octahedra; dominant exposed facets are {111} and {100}, reminiscent of the Wulff polyhedron for FCC metals.

- Surface stiffness: {111} nanoplates display enhanced in-plane stiffness. The thinnest nanoplate (3 layers: 2 surface + 1 bulk) is >30% stiffer than the bulk in both [110] and [112] in-plane directions; surface and bulk directional moduli for these directions are equal to each other in-plane. This surface stiffening explains HS exceedance at nanoscale.

- Anisotropy robustness: Even after accounting for aluminum’s shear modulus anisotropy (G_min to G_max), Nano-TO designs still exceed the corresponding HS upper bounds at small sizes.

Discussion

The central research question—can atomistically optimized architectures leverage nanoscale surface effects to achieve elastic properties beyond conventional continuum bounds?—is answered affirmatively. Nano-TO directly manipulates atomic occupancy to optimize elastic strain energy under hydrostatic loading, producing simple, highly connected nanoplate-based architectures with stiff {111} surfaces that elevate the effective bulk modulus beyond the HS upper bound at small cell sizes. As the unit cell size increases, surface effects diminish and responses converge to continuum predictions, with the Nano-TO design approaching the HS limit from above while maintaining superiority over TPMS across sizes. Because continuum FEM-based topology optimization cannot capture coordination-dependent surface bond strengthening, such designs are inaccessible to traditional methods. The findings underscore the importance of atomistic modeling for nanoscale materials design and suggest that surface orientation and layer thickness are key design levers for maximizing elastic performance. The methodology is extensible to multiobjective design (e.g., combining bulk modulus with other components of C_ij) and potentially to other properties correlated with elastic moduli.

Conclusion

This work introduces Nano-Topology Optimization, an atomistic topology optimization framework that enables atom-by-atom materials design. Applied to aluminum, Nano-TO discovers nanostructures that outperform widely studied TPMS (gyroid, diamond, primitive) and, at small cell sizes, exceed the Hashin–Shtrikman upper bound for the bulk modulus by exploiting surface-induced stiffening of {111} nanoplates. The approach demonstrates that theoretical continuum bounds can be surpassed at the nanoscale where surface effects are significant and identifies simple, high-performance architectures with near-cubic symmetry and BCC-arranged truncated octahedral voids. Future directions include: extending Nano-TO to other base materials with accurate interatomic potentials; multiobjective optimization for combined elastic properties and other functionalities; investigating the linkage between optimal elastic designs and Wulff constructions; reducing sensitivity to initial conditions; and integrating machine learning surrogates to dramatically accelerate sensitivity evaluations for larger-scale problems.

Limitations

- Dependence on initial structures: The optimization landscape is non-convex, and outcomes vary with initialization, necessitating multiple runs to find strong local optima.

- Model fidelity: Results hinge on the accuracy of the interatomic potential (EAM for Al). Transferability to other materials requires similarly validated potentials; quantum effects are not explicitly treated.

- Computational cost: Atom-by-atom design scales poorly with system size; even micrometer-scale domains are intractable without surrogate models or ML acceleration.

- Scope: Demonstrations focus on aluminum and elastic properties (bulk modulus, C33). Generalization to other property targets and environmental conditions (temperature, defects) remains to be validated.

- Size effects: HS exceedance occurs only at small cell sizes where surfaces dominate; at larger sizes, properties converge to continuum bounds.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.