The Arts

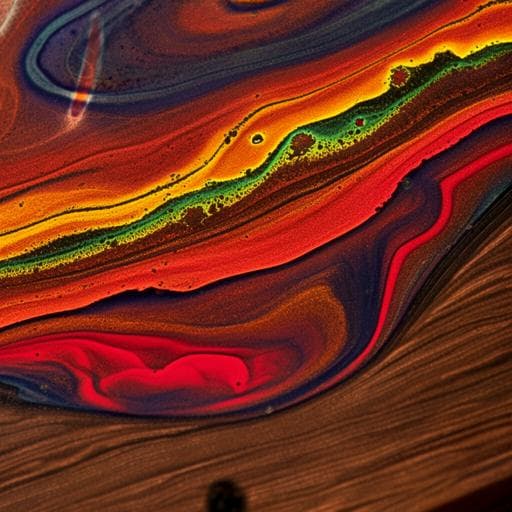

Multi-analytical investigation into the materials and techniques of paintings on Northern Wei Dynasty (398–494 CE) coffin planks excavated from Shanxi, China

Z. Guo, S. Cai, et al.

This fascinating research by Zhiyong Guo and colleagues dives deep into the intricate world of coffin plank paintings from a Northern Wei tomb, revealing the use of vibrant pigments like cinnabar, pararealgar, and an intriguing mix of indigo and orpiment. Discover how cutting-edge non-invasive and micro-invasive techniques unveil secrets of art history and conservation!

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.