Earth Sciences

Mineral reactivity determines root effects on soil organic carbon

G. Liang, J. Stark, et al.

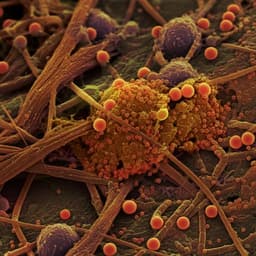

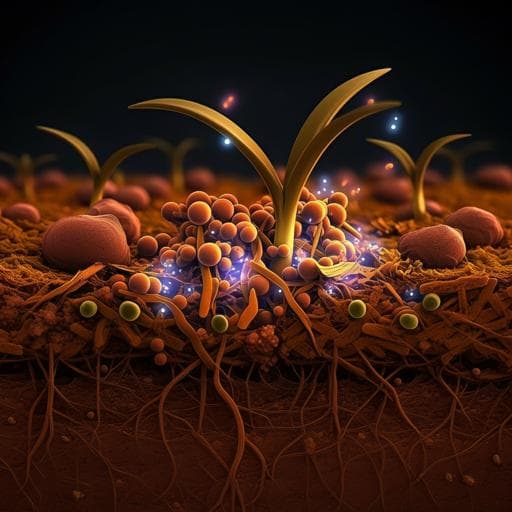

What controls the size and turnover of the SOC pool? Historically, SOC stocks were attributed to plant traits, with chemically complex inputs decomposing slowly and thus forming the longest-lived pools. This view has shifted: soil C dynamics are now recognized as largely governed by microbes and minerals. Microbes mediate SOC loss via decomposition and mineralization to CO2, yet long-residence-time SOC predominantly comprises microbial products associated with mineral surfaces. Thus, microbial physiology partitions new C inputs between SOC formation and loss, influencing both the quantity and persistence of below-ground C. Importantly, stabilization of organic matter (formation of slowly cycling pools) is not synonymous with increases in total SOC at a given time. Particulate C can accumulate yet remains vulnerable and fast-cycling, whereas mineral-associated C turns over more slowly but is constrained by mineral surface saturation. Furthermore, C is lost to respiration as it is transformed into microbial precursors of stable SOC, linking stabilization and loss. Clarifying targets for increased soil C sequestration is critical for climate mitigation, as strategies to protect particulate versus mineral-associated pools may diverge. Multiple interacting drivers across the mineral–microbe–plant continuum shape SOC cycling, including soil parent material chemistry (which sets the capacity to retain fresh C and influences microbial community structure) and microbial community composition. Evidence suggests clay mineralogy better predicts SOC dynamics than bulk clay content at global scales, with highly reactive minerals (e.g., phyllosilicates with high surface area and oxyhydroxides) associated with larger mineral-associated SOC pools. Conversely, other studies report microbial community structure, particularly fungi, exerts greater influence on SOC dynamics, especially for particulate organic matter. Similarly, literature on plant input chemistry reveals contradictions: the MEMS framework posits that bioavailable plant compounds are efficiently transformed into microbial biomass and then mineral-associated C, yet enhanced microbial efficiency may also increase exoenzyme production and SOC loss, yielding uncertain consequences for total SOC stocks. The mechanism and point-of-entry of inputs matter: root exudates, which contain simple compounds and are delivered near reactive mineral surfaces, can promote stabilization through the microbial carbon pump but also accelerate decomposition via priming, making roots a double-edged sword for SOC. Here, we used artificial root–soil systems to test three questions. First (H1), whether minerals or microbes principally control the soil C balance: we predicted clay mineralogy would dominate through direct sorption and indirect effects on microbial dynamics. We independently manipulated microbial assemblages (fungi+bacteria vs bacteria-only) and mineral composition (constant clay content but varying reactivity) and quantified microbial shifts and C cycling over three months. Second, we asked how chemistry and point-of-entry of new C inputs affect interactions with microbes and minerals (and hence fate), predicting that more bioavailable inputs would increase microbial biomass and mineral-associated C, especially with reactive minerals, but also increase respiration (H2a), and that exudate C would enhance decomposition/mineralization of complex inputs (H2b). Third (H3), we hypothesized a negative correlation between mineral-associated C formation and respiration across treatments, assuming protection of stabilized C reduces substrate available for mineralization. We show that mineral surfaces, microbes, and root exudates interact to control mineral-associated SOC formation, that input chemical complexity had negligible impact on stabilization or microbial community composition, and that C stabilization correlated positively with C loss, indicating subtle changes in SOC stocks can mask large opposing fluxes.

The authors synthesize evidence that mineralogy and microbial communities jointly regulate SOC. Globally, highly reactive minerals (high surface-area phyllosilicates and iron oxyhydroxides) are associated with larger mineral-associated SOC pools, often outperforming bulk clay content as predictors of SOC. In contrast, several field and lab studies indicate microbial community structure—particularly fungal contributions—strongly influences SOC dynamics and particulate organic matter turnover, highlighting scale and pool-identity dependencies. Conceptual frameworks such as MEMS propose that the most labile plant compounds are efficiently incorporated into microbial biomass and subsequently stabilized on minerals, underpinning the microbial origin of stable SOC. Yet increased microbial growth efficiency can also elevate exoenzyme production and SOC mineralization, complicating predictions for total SOC. Root-derived inputs are emphasized as key drivers due to their bioavailability and proximity to mineral surfaces (microbial carbon pump), but they can also induce priming, accelerating decomposition of existing organic matter. Mineral traits matter mechanistically: metal oxides like goethite possess variable charge and highly reactive hydroxyl groups that form strong ligand-exchange bonds with carboxyl/hydroxyl-rich organic molecules, whereas negatively charged phyllosilicates (e.g., kaolinite, montmorillonite) bind via weaker ionic interactions or cation bridging. These distinctions underpin divergent capacities for stabilization and susceptibility to exudate-induced destabilization reported in prior studies.

Experimental design: The study used artificial soils with equal organic matter and clay contents but differing mineral reactivity: low (kaolinite), medium (montmorillonite), and high (montmorillonite + goethite). Microbial inoculum treatments established distinct communities: fungi + bacteria (FB) versus bacteria-only (BO, generated by filtering a compost slurry through 2 µm and adding captan to exclude most fungal propagules). Artificial root systems were constructed from ten 10 cm polysulfone hollow fiber dialysis membranes connected to a 5 mL reservoir, permitting diffusion of molecules < 60 kDa and positioned flush with the soil surface to mimic realistic spatial exudation patterns. A real soil control (sterilized coarse-silty Xeric Haplocalcid) was also included and subjected to similar inoculum, root, and C input treatments. Two-phase incubation: Phase 1 (months 1–3) manipulated mineralogy (3 levels), inoculum (FB vs BO), and root exudation (exudate vs water-only control) across 288 artificial-soil microcosms (N = 48 per mineral × inoculum treatment; half received exudates). Exudate solution (glucose, fructose, sucrose, tryptic soy broth) was delivered via artificial roots at 3.7 µg C g⁻¹ soil d⁻¹. At month 3, a subset was destructively harvested for microbial biomass, extracellular enzyme activities, and microbial C use efficiency (CUE). Phase 2 (months 4–13) further applied aboveground C inputs directly to the soil surface to vary input chemistry: glucose (monomer), cellobiose (disaccharide), or xylan (polysaccharide), each adjusted with NH4Cl to C:N 25:1 and supplied at 27 µg C g⁻¹ soil d⁻¹. Root exudation rates were increased tenfold in the exudate treatment to 37 µg C g⁻¹ d⁻¹. The full factorial Phase 2 comprised mineralogy × inoculum × root exudation × C-input chemistry, yielding 36 treatment combinations with 6 replicates each (216 artificial-soil microcosms). Amendments were applied biweekly; destructive harvests occurred at months 7 and 13. Measurements: CO2 fluxes were measured every two weeks; microcosms were capped for 24 h before headspace sampling and analyzed by gas chromatography. CUE was determined at the end of Phase 1 by adding 13C-labeled glucose (0.116 mg C g⁻¹ soil, 26 atom% 13C) and partitioning 13C between microbial biomass (via chloroform-fumigation extraction with 0.5 M K2SO4) and 13CO2 respired over 24 h using isotope analysis; the calculation assumed no abiotic sorption of glucose. Microbial biomass C was measured by fumigation-extraction. Mineral-associated organic C (MAOC) was quantified as the heavy fraction C after density fractionation with sodium polytungstate (1.6 g cm⁻³), with near-complete mass recovery (~100%). Unprotected C (particulate and dissolved) was estimated by mass balance as total available C inputs minus recovered C (cumulative respiration + microbial biomass C + MAOC). Total C pool was defined as total available C minus cumulative respiration, assuming closed-system conditions. Extracellular enzyme activities (e.g., β-xylosidase, acid phosphatase, β-glucosidase, cellobiohydrolase, leucine aminopeptidase, β-N-acetylglucosaminidase) were assayed following established protocols. Microbial communities: DNA was extracted (DNeasy PowerSoil), bacterial (515F-806R) and fungal (ITS1f-ITS2) marker genes were sequenced (Illumina MiSeq). QIIME2 with DADA2 denoised reads to ASVs; taxonomy was assigned using UNITE (fungi) and Greengenes (bacteria). Statistical analysis: Phase 1 and Phase 2 were analyzed separately. Three-way ANOVAs assessed effects of root exudates, inoculum, and mineralogy in Phase 1; Phase 2 ANOVAs additionally included C input chemistry and harvest time. Mixed models (lme4) analyzed repeated CO2 fluxes with microcosm as random effect; cumulative respiration was computed by trapezoidal integration (R package flux). Microbial community composition was evaluated via NMDS on Bray–Curtis distances and PERMANOVA; outliers were removed where identified, and transformations applied to meet assumptions.

Phase 1 (months 1–3): Contrary to H1, mineral reactivity did not affect respiration. Microcosms inoculated with bacteria-only (BO) had 20% greater respiration than those with fungi+bacteria (FB), resulting in a 4% larger total C pool in FB than BO by mass balance. Inoculum strongly altered microbial communities: BO reduced bacterial species richness ~4-fold and fungal richness ~2-fold, with most fungi in BO belonging to Eurotiomycetes; BO communities exhibited ~11% higher C use efficiency. Mineralogy shaped community composition and function: kaolinite soils had greater bacterial diversity, lower microbial CUE, and smaller microbial biomass than montmorillonite-dominated soils. Low exudation rates had only minor impacts on respiration and communities. Phase 2 (months 4–13): Increasing inputs led to a ~70% rise in respiration rates and the emergence of a mineral-associated C pool, stabilizing on average 20.9% of total available C. Across treatments, MAOC comprised 47.7 ± 1.0% of SOC, while microbial biomass accounted for 30.8 ± 0.7% (real-soil controls: 16.3 ± 0.6%). Inoculum effects persisted: MAOC was larger in FB than BO microcosms, especially in the cellulose treatment. Goethite-containing soils showed the highest CO2 fluxes and MAOC, indicating that metal oxides simultaneously accelerated stabilization and loss. Input chemistry effects were limited: respiration was 41% lower with xylan than with glucose or cellobiose, microbial biomass was slightly larger with xylan than glucose, and MAOC formation did not differ among input types. In glucose-amended microcosms, MAOC was 25% lower when root exudates were present. Root–mineral interactions: Root exudates increased cumulative respiration by ~29% on average (effect diminishing with increasing mineral reactivity) and increased microbial biomass by ~13% (effect strengthening with mineral reactivity). Exudates decreased MAOC by 42–26% in kaolinite and montmorillonite soils but increased MAOC by ~10% in goethite-containing soils. Root exudates generally increased bacterial and fungal diversity and shifted communities toward taxa common in real soils (e.g., Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes). Stabilization–loss relationship: Across 216 Phase 2 microcosms, MAOC formation was positively correlated with cumulative respiration (R² = 0.131, P = 0.029) after accounting for C input amounts, indicating that increases in slow-cycling pools were accompanied by greater C losses.

The results show that SOC stabilization and loss are co-regulated by interactions among mineral surfaces, microbial communities, and root exudates. Contrary to expectations, mineral reactivity did not govern early respiration dynamics, which were more sensitive to inoculum composition; fungi presence constrained respiration and supported larger SOC pools via lower C loss. With increased inputs, mineralogical controls became evident: goethite-enhanced systems exhibited both greater MAOC and higher respiration, suggesting that reactive metal oxides promote strong organo–mineral associations while potentially coupling iron redox cycling with C mineralization in microsites. Surprisingly, the chemical complexity of aboveground inputs (glucose, cellobiose, xylan) exerted minimal influence on MAOC or community composition, indicating that microbial physiological adjustments can buffer stabilization outcomes against input chemistry. Root exudates acted as a double-edged sword: they stimulated microbial growth and respiration but had mineral-dependent effects on MAOC—disrupting weaker ionic or cation-bridged associations on phyllosilicate clays while enhancing stabilization on metal oxides via microbially produced carboxyl/hydroxyl-rich metabolites that form strong ligand-exchange bonds. The observed positive correlation between stabilization (MAOC) and loss (respiration) across treatments refutes the hypothesis of a trade-off (H3) and underscores that growth of slow-cycling pools often coincides with increased C processing and CO2 release. These findings reconcile divergent views by emphasizing that mineral traits modulate root effects and that microbial community composition and activity determine how inputs are partitioned between stabilized pools and respiratory loss.

This study demonstrates that mineral reactivity mediates root effects on SOC: root exudates can either diminish or enhance mineral-associated C depending on whether soils are dominated by phyllosilicate clays or contain reactive metal oxides like goethite. Microbial community composition influences C losses and stabilization, but the chemistry of aboveground inputs (from monomers to polysaccharides) had limited impact on MAOC under the conditions tested. Across treatments, increased stabilization coincided with greater respiration, implying that growth of slow-cycling SOC pools generally comes at the cost of higher C losses. These insights suggest that soil C management and sequestration strategies should explicitly account for mineralogical context and root-driven processes rather than focusing primarily on altering input chemical complexity. Future research should test these mechanisms in field settings and with whole-plant litters, quantify how varying exudate compositions and rates interact with diverse mineral assemblages (including different metal oxides), resolve microbial metabolic pathways producing strongly sorptive metabolites, and evaluate long-term dynamics and saturation thresholds of mineral-associated C under realistic environmental variability.

The experiment used sterilized, artificial soils with controlled mineralogy and microbial inocula, which may limit generalization to field conditions. Root inputs were simulated via an artificial system, and Phase 2 input rates were at the high end of natural ranges, contributing to unusually large microbial biomass fractions of SOC. Aboveground inputs were individual compounds (glucose, cellobiose, xylan) rather than complex plant litters, which the authors note may obscure ecological dynamics observed in real ecosystems. The simulated exudate solution did not include carboxyl/hydroxyl-rich compounds; inferred stabilization on goethite likely depended on microbially produced metabolites. Some calculations relied on assumptions: CUE estimation assumed no abiotic sorption of glucose, and mass-balance estimates of unprotected C and total C pools assumed closed systems with no C losses other than respiration.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.