Psychology

Forming cognitive maps for abstract spaces: the roles of the human hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex

Y. Qiu, H. Li, et al.

Using fMRI and a deep neural network to track learning, this study reveals how the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and prefrontal regions construct cognitive maps in multidimensional abstract spaces—distinguishing exploration (hippocampus and lateral PFC linked to better learning and accuracy) from exploitation (OFC and retrosplenial cortex linked to lower learning and accuracy). This research was conducted by Yidan Qiu, Huakang Li, Jiajun Liao, Kemeng Chen, Xiaoyan Wu, Bingyi Liu, and Ruiwang Huang.

~3 min • Beginner • English

Introduction

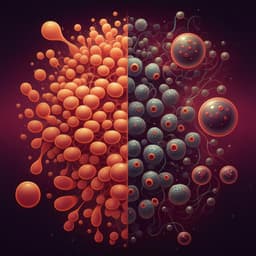

The study investigates how humans build cognitive maps to guide flexible behavior in nonphysical, multidimensional abstract spaces. Building on Tolman’s concept of cognitive maps and subsequent work suggesting that the hippocampal–entorhinal (HIP–EC) system and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) support map-based behavior across physical and abstract domains, the authors ask how HIP, EC, and OFC contribute to learning and representation during exploration and exploitation. They hypothesize that these regions will show distinct activation and representational patterns across learning stages, reflecting complementary roles: the hippocampus in forming and updating spatial memory representations and the OFC in integrating sensory information to support decision-making and inference in abstract spaces.

Literature Review

Prior work identifies the HIP–EC system as central to constructing cognitive maps by encoding spatial layouts, nonspatial structures, and providing a spatiotemporal framework for experiences. The hippocampus supports learning, spatial reasoning, and relational memory, dynamically updating object representations and consolidating memories, with place cells mapping locations and replaying sequences. Stage-dependent hippocampal activation has been observed when tracking goal distance in familiar versus novel environments and representing conceptually distinct stimuli after learning. The OFC encodes cognitive maps of task state space, supports planning and inference under partial observability, and may subsume functions like value prediction and credit assignment through its map representations. OFC integrates inputs from sensory areas, HIP, and striatum, and is thought to encode aspects of task structure complementary to HIP. Despite evidence for distinct roles, how HIP and OFC collaborate during learning to support flexible behavior in abstract spaces remains unclear.

Methodology

Participants: Twenty-seven healthy adults (14 women; mean age 21.78 years; range 18–29) with normal or corrected-to-normal vision participated; none reported neurological conditions. Two subjects were excluded due to poor task performance, yielding n=25 for analyses. IRB approval (SCNU #2019-3-062) and informed consent were obtained.

Task and stimuli: Two basic symbols (hat, dog) were defined, each with four manipulable features forming dimensions. Hat features: tilt angle, brim width, pompom size, color lightness. Dog features: tail direction, body length, leg length, color tone. Abstract spaces of 1D, 2D, and 3D were constructed by randomly selecting 1–3 features of a designated primary symbol (P) per subject; the other symbol served as control (C). Five spaces were used during fMRI in fixed order: S1P (1D, P), S2C (2D, C), S2P (2D, P), S1C (1D, C), S3P (3D, P); S1P, S2C, S3P defined Set 1; S1C, S2P defined Set 2. Half of subjects used hat as primary, half dog. Each space contained discrete locations defined by 1-, 2-, or 3-tuples specifying distances along feature axes.

Navigation task: In each abstract space, subjects completed 10 paths from random starting points to random destinations. Each path comprised multiple trials: current location (2 s), goal (4 s), options (four candidate neighboring locations arranged clockwise relative to current; two left-hand buttons mapped to first two options, two right-hand buttons to remaining options). Selecting the destination yielded feedback (“Achieved!” with coin), otherwise the chosen option became the next current location; paths could be terminated with 20% probability on suboptimal choice (“Break!”), still included in analyses. Inter-trial interval 3–9 s; inter-path fixation 6–13 s. Response accuracy (RA) per step was 1 for optimal option, 0 otherwise; response time (RT) recorded per step.

MRI acquisition: Siemens Prisma 3T, 64-channel head/neck coil. Task-fMRI EPI (SMS/MB) parameters: TR=1500 ms, TE=31.0 ms, flip angle=70°, multiband factor=3, FOV=211×211 mm², matrix 88×88, slice thickness=2.4 mm, voxel size 2.4 mm³, A–P phase encoding, bandwidth 2186 Hz/px, 60 interleaved slices. Field map: double-echo GRE (TR=620 ms, TE1/TE2=4.92/7.38 ms, flip angle=60°, voxel 2.4 mm³, 60 slices). Structural T1 MP-RAGE: TR=1800 ms, TE=2.07 ms, flip angle=9°, voxel 0.8 mm³. Scan order: localizer, resting-state fMRI, field map, five task-fMRI runs (1D 10 min/400 vols; 2D and 3D 15 min/600 vols), T1, T2 SPACE, HARDI. All data acquired within ~110 min; rs-fMRI and HARDI not analyzed.

Preprocessing: fMRIPrep 21.0.0 (Nipype 1.6.1). Steps: reference volume and skull-stripping; head-motion estimation (FSL mcflirt) with six parameters included as nuisance covariates; field-map registration; slice-time correction to 50% acquisition range (AFNI 3dTshift); BBR co-registration to T1 (FreeSurfer); framewise displacement (FD) calculation; tissue signals extraction (CSF, WM, GM); exclusion threshold average FD>0.25 (none excluded); resampling to 2.0 mm³ MNI space; high-pass filter cutoff 1/100 Hz. Smoothing 6 mm FWHM for univariate analyses; unsmoothed data for RSA.

Behavioral analyses: Paths classified into early (first 3), mid (middle 4), and late (last 3) learning. Linear mixed-effects models (LMM; lmerTest) assessed RA_path and RT_path. LMM1: early vs late; LMM2: Set 1 vs Set 2; LMM3: exploration vs exploitation (defined below). Statistical tests: paired t-test for fixed effects; significance p<0.05.

Learning level and stage categorization: For each path, constructed B matrix (N_step×2) with RA and RT per step. A deep neural network (TensorFlow 2.8) with input layer, two hidden layers (64, 32 units; ReLU activation), and softmax output (2 units: P(early), P(late)=1−P(early)) was trained to discriminate early vs late paths per dimensionality. Training/test split: in each dimensionality, 2 paths randomly selected as test set; remaining labeled paths as training set (1D/2D: 10 paths; 3D: 4 paths). Optimizer: Adam (lr=0.001); categorical cross-entropy loss; 100 epochs; model accuracy averaged across epochs; one-sample t-test against chance (0.25). The trained DNN estimated P(early) per path as learning level. K-means clustering (k=2; optimized seeding) on learning levels categorized paths into exploration (cluster with higher P(early)) and exploitation stages. LMM3 then tested RA_path and RT_path differences between stages.

Univariate fMRI GLMs: FSL GLM1 contrasted exploration vs exploitation paths (plus feedback, 6 motion regressors; fixation baseline), convolved with double-gamma HRF; subject-level COPE maps combined via fixed effects; group-level random effects with age and gender covariates; paired t-test; GRF correction p<0.05 (cluster-forming p<0.001). GLM2: path-wise regressors and feedback plus motion; learning level entered as regressor to identify learning-associated activation; repeated-measures ANOVA tested dimensionality effects. GLM3: navigation, feedback, and RA regressor to detect activation associated with step-wise accuracy; one-sample t-test; GRF correction.

Representational similarity analysis (RSA): Whole-brain searchlight RSA (NeuroRA), separately for exploration and exploitation. Theoretical RDM: Euclidean distances between destinations across paths. Neural RDM: voxel-wise dissimilarities (1−r) between path-specific parameter estimation (PE) maps from GLM2 (unsmoothed data) within each searchlight (3-voxel cube; stride 1). For each subject and stage, Spearman’s rho computed between theoretical and neural RDMs, Fisher transformed; stages compared via paired t-test; TFCE with 10,000 permutations and FWE correction identified significant clusters representing destinations more accurately in exploitation than exploration.

Key Findings

Behavioral: Subjects’ response accuracy improved across learning. LMM1 showed lower RA_path in early vs late learning (β=−0.13, SE=0.03, t=−3.89, p<0.001); RT_path difference was not significant (β=0.22, SE=0.13, t=1.76, p=0.079). Transfer learning: higher RA_path in Set 2 vs Set 1 (β=−0.14, SE=0.03, t=−4.86, p<0.001); RT_path no difference (β=−0.03, SE=0.09, t=−0.37, p=0.711). DNN predicted learning levels above chance (t=41.74, p<0.001); no accuracy differences across 1D/2D/3D (repeated measures ANOVA F(2,48)=8.68, p=0.134). K-means assigned ~50% paths to each stage (exploration: 24.84±3.53; exploitation: 25.16±3.53), with higher RA_path and shorter RT_path in exploitation than exploration (LMM3 RA: β=−0.15, SE=0.03, t=−5.63, p<0.001; RT: β=0.17, SE=0.08, t=2.06, p=0.040).

fMRI univariate (GLM1–3): Exploration>Exploitation showed stronger activation in bilateral hippocampus, lateral prefrontal cortex (inferior/middle frontal gyri), insula, inferior parietal lobule, thalamus, visual cortex, and cerebellum. Exploitation>Exploration showed stronger activation in right posterior cingulate cortex and right superior frontal gyrus; consistent with the abstract and discussion, medial OFC and retrosplenial cortex also showed greater engagement during exploitation. Learning-level associations (GLM2) were positive in right hippocampus, bilateral middle and superior frontal gyri, bilateral insula, postcentral gyrus, right IPL, and cerebellum; negative associations in medial frontal gyrus and PCC. Accuracy associations (GLM3): positive in left hippocampus, bilateral middle and inferior frontal gyri, right lingual gyrus/visual cortex, right thalamus; negative in OFC-related regions including ACC, IPL, PCC, retrosplenial cortex, middle/superior temporal gyri, parahippocampal gyrus.

RSA: Whole-brain searchlight RSA revealed more accurate destination representations in exploitation than exploration in bilateral entorhinal cortex, bilateral orbitofrontal cortex, left hippocampus, bilateral cuneus, left inferior temporal gyrus, right anterior cingulate cortex, left frontal pole, bilateral superior frontal gyrus, left inferior frontal gyrus, and right cerebellum.

Interpretation: The hippocampus and lateral PFC are engaged during exploration and learning, with hippocampal activation positively tracking accuracy. The OFC and retrosplenial/mPFC regions are more engaged during exploitation and show negative associations with accuracy, consistent with roles in inference and using learned maps. Destination representations improve with learning in HIP–EC–OFC circuitry.

Discussion

The findings demonstrate distinct and complementary roles of hippocampal–entorhinal and prefrontal–orbitofrontal systems in constructing and using cognitive maps in abstract spaces. Behavioral improvements and transfer learning indicate that participants refined internal representations and could generalize task structure across visually different spaces of the same dimensionality. Neural results show an exploration network (hippocampus, lateral PFC, visual cortex, thalamus, IPL, insula) supporting mapping, updating, and memory formation, with hippocampal activation positively related to accuracy and learning level. An exploitation network (medial prefrontal cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, retrosplenial cortex, PCC/SFG) supports inference, outcome evaluation, and alignment of internal maps with sensory inputs, with negative associations to accuracy suggesting reliance on established representations over trial-by-trial optimization. RSA confirms that destination representations become more accurate in exploitation within HIP–EC–OFC circuitry, indicating strengthened map-based coding of goals. Together, these results address the research question by showing how MTL and OFC collaborate across learning stages to support flexible decision-making in multidimensional abstract spaces.

Conclusion

This study introduces a multidimensional abstract-space navigation paradigm combined with DNN-derived learning levels to separate exploration and exploitation. It shows behavioral improvements and transfer learning, and identifies distinct neural networks: hippocampus–lateral PFC–visual cortex predominating in exploration with positive links to accuracy, and mPFC/OFC/RSC predominating in exploitation with negative links to accuracy. RSA reveals improved destination representations in entorhinal cortex, hippocampus, and OFC during exploitation. These contributions advance understanding of how the brain encodes and utilizes cognitive maps for abstract decision spaces. Future work should employ more naturalistic, complex abstract spaces, test additional modalities and tasks, and optimize acquisition protocols (e.g., EPI parameters, multiband factors, slice orientation) to improve BOLD sensitivity in MTL/OFC regions and generalize findings.

Limitations

The abstract spaces were artificially constructed and may not capture the complexity of real-world concepts; subjects might have processed dimensions separately despite instructions to integrate features. BOLD sensitivity in target regions (hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, OFC) is susceptible to acquisition choices (hardware, multiband acceleration, slice orientation, susceptibility effects, spatial resolution), potentially affecting signal quality and detection of effects.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.