Interdisciplinary Studies

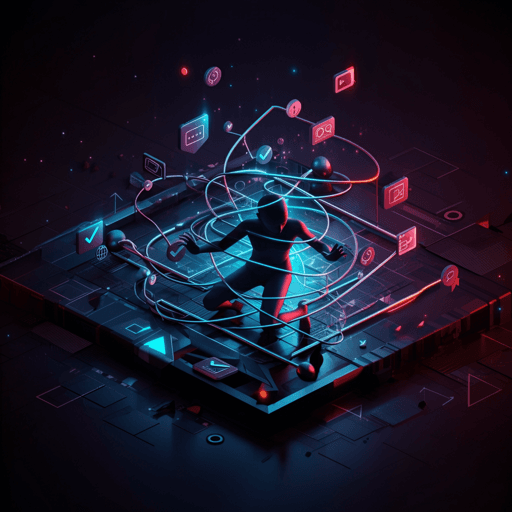

An Ontology of Dark Patterns: Foundations, Definitions, and a Structure for Transdisciplinary Action

C. M. Gray, N. Bielova, et al.

Deceptive and coercive "dark patterns" undermine consumer choice and blur responsibilities across designers, technologists, and regulators. This paper harmonizes ten academic and regulatory taxonomies into a three-level ontology with standardized definitions for 64 dark-pattern types, and shows how it can drive translational research and regulatory action. This research was conducted by Colin M. Gray, Nataliia Bielova, Cristiana Santos, and Thomas Mildner.

Related Publications

Explore these studies to deepen your understanding of the subject.